This manual mainly addresses the situation where ASF invades a country or zone formerly considered free from ASF. Should such an emergency occur, all initiatives would be directed towards rapid containment of the disease to the primary focus or zone of infection and eradication within the shortest possible time to avoid spread and possible progression to endemic status.

In certain countries where ASF is already endemic, notably in eastern and southern Africa, eradication of the disease is not a viable option. This is because the virus is entrenched in warthog and possibly other wild suid populations and a sylvatic cycle occurs between warthogs and Ornithodoros ticks. This does not mean, however, that nothing can be done in these areas. In commercial piggeries, ASF is easily prevented by control actions preventing contact between warthogs, Ornithodoros ticks and domestic pigs. Commercial pig farms in endemic areas may be protected from ASF by double pig-proof perimeter fencing, a solid wall or single pig-proof fencing if the pigs are permanently housed in solid structures and are unable to approach the fence. Sanitary precautions should be in place, such as limited access for people and vehicles, disinfectant footbaths and measures normally taken to protect the health of intensively farmed animals. Where practicable, efforts should be made to minimize the number of free-roaming or poorly controlled domestic pigs that may have access to infected pigs and material and that could act as a reservoir of infection. In future it may be possible to develop ASF-resistant breeds of pigs for use in endemic areas.

Even in countries where ASF is endemic, it is possible to develop ASF-free zones through strict pig movement and quarantine controls and by enhancing the biosecurity of pig-production units. Active surveillance involving owner observation and farm and abattoir veterinary inspection is a prerequisite for credibility.

There are several epidemiological and other factors which influence eradication strategies for ASF, some favourable but most unfavourable. They include the facts that:

The above factors make ASF one of the more difficult TADs to eradicate. Nevertheless there are numerous examples from Europe, Africa and South America that demonstrate that ASF can be eradicated from countries by concerted, well organized campaigns.

In the absence of vaccines, the only available option for ASF eradication is stamping out by slaughter and disposal of all infected and potentially infected pigs. This is a proven method which has succeeded in eradicating ASF and other serious transboundary diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease and rinderpest.

The main elements of a stamping-out policy for ASF are:

The above procedures must be applied for a period long enough to eradicate the disease and should be accompanied by extensive public-awareness campaigns.

Stamping out tends to be a resource-intensive method of disease eradication in the short term. It generally proves to be the most cost-effective method, however, and allows countries to declare freedom from disease in the shortest time. The latter may be important for international trade purposes.

Zoning is the proclamation of geographical areas in which specific disease-control actions are to be carried out. The zones are concentric areas around known or suspected foci of infection, with the most intensive disease-control activities in the inner zones. Zoning is one of the early actions to be taken when there is an incursion of ASF into a country. The size and shape of the zones may be determined by administrative or geographical boundaries or by epidemiological or resource considerations. However, because ASF is not spread by aerosol but by movement of infected material, it is important to bear in mind that transmission can occur overnight over hundreds or thousands of kilometres by road or air. During an epizootic, it would be short-sighted to depend on the declaration of infected zones to contain the disease unless there is a high level of confidence that the movement of pigs or dangerous materials such as pig meat from infected to free zones can be prevented by geographical barriers or control measures. Experience has demonstrated that establishment of a cordon sanitaire is far from simple in many countries and that such measures are easily evaded. It is certain that poorly organized pig farms distant from the zone of infection may be at greater risk than well managed commercial farms within the infected zone.

Zoning is now recognized as an important principle in the definition by OIE of national animal health status.

FIGURE 4

Zoning

It is important to have simple logistics, for example an office and desk, maps and writing

materials, ready to hand to carry out emergency planning such as zoning.

Infected zones

An infected zone encompasses the area immediately surrounding one or more infected farms, premises or villages. Its size and shape are influenced by topographical features, physical barriers, administrative borders and epidemiological considerations. OIE recommends that it should have a radius of at least 10 km around disease foci in areas with intense livestock raising and 50 km in areas of extensive livestock raising. Intensive livestock raising would mean areas where pigs are securely confined in premises or farms; extensive livestock raising areas are those where some pigs are allowed to roam or are poorly controlled.

When dealing with a disease like ASF where there is no aerosol transmission, the use of radii to define infected zones may not be appropriate in practice. In rural areas in a number of countries, a proportion of the pigs in any area will be poorly controlled, so declaration of 50 km zones where expensive and drastic measures will be applied is unnecessary and impractical. In order to determine infected zones, the extent of the focus of infection must be determined and well managed farms that have escaped infection must not be regarded as infected. On the other hand, strict vigilance must be maintained over a much wider area, depending upon known patterns of pig movements determined by marketing and other considerations.

In the initial stages of an outbreak, when its extent is not well known, it would be wise to declare larger infected zones and then progressively reduce them as active disease surveillance reveals the true extent of the outbreak.

Surveillance (control) zones

These zones are much larger and surround one or more infected zones. They may cover a province or administrative region and in many cases cover a whole country.

ASF-free zones

These encompass the rest of the country. Because of the potential of ASF for wide dissemination, however, it is recommended that all parts of a country experiencing a first outbreak are placed under a high level of surveillance. The emphasis in ASF-free zones should be on strict quarantine measures to prevent entry of the disease from infected zones and continuing surveillance to provide confidence of continuing freedom. Information should be provided in these zones on the same basis as zones in which the outbreak occurs. This information should be extended as quickly and securely as possible to neighbouring countries.

Infected premises and dangerous-contact premises

In this context, an infected premises (IP) means an epidemiological entity where pigs have become infected. It may be a single farm or household or an entire village or settlement. It may be a livestock market or abattoir. A dangerous-contact premises (DCP) is one for which there are epidemiological grounds to suspect that it has become infected, even though the disease is not yet clinically apparent. This might be through close proximity or as a result of epidemiological tracing.

There are two objectives in the infected zone: to prevent further spread of infection through quarantine and livestock movement controls and to remove sources of infection as quickly as possible through slaughter of potentially infected pigs, safe disposal of carcasses and decontamination.

The balance of actions towards these objectives depends on circumstances. An important decision must be made between two options. If pigs in the infected zone are not well controlled and there is a risk of further rapid spread of the disease or transfer to wild pigs, or if resources for surveillance and imposition of quarantine and movement controls are inadequate, it may be expedient to slaughter all pigs in the infected zone or in specific areas of the zone. On the other hand, if pigs are securely contained on farms and resources for surveillance and imposition of quarantine and movement controls are adequate, the best decision would be to slaughter pigs only on IPs and DCPs.

Disease surveillance and other epidemiological investigations

Intensive active surveillance for ASF must be undertaken, with frequent clinical examination of pig herds by veterinary officers or inspection teams. These officers or teams must of course practise good personal decontamination procedures to avoid carrying infection to the next farm they inspect.

At the same time, traceback and traceforward investigations should be carried out whenever an infected pig herd is found. Tracing back means determining the origin of any new pigs brought on to an IP in the three or four weeks before the first clinical ASF cases, which may have been the source of infection, and inspecting the farms in question. Tracing forward means determining the destination of pigs leaving the IP prior to or after the first clinical cases. Farms that may have become infected by these pigs are then inspected. Traceback and traceforward investigations quickly become complicated if pigs have transited through livestock markets or saleyards.

Quarantine of IPs and DCPs

IPs and DCPs should be immediately quarantined with a ban on the exit of live pigs, pig meat and other potentially contaminated materials, pending further disease-control action. Vehicles and other equipment should be disinfected before leaving.

Movement controls

There should be a complete ban on the movement of live pigs, pig meat and pig products inside and out of the infected zone. Great care is required to ensure that neither live pigs nor pig meat are smuggled out of the infected zone. Because of the high risk that they constitute for spread of infection, pig markets and abattoirs should be closed.

Slaughter of infected and potentially infected pigs

All pigs on IPs and DCPs, or in a larger area if necessary, must be slaughtered immediately, whether they are obviously diseased or not. Owners should be asked to collect and confine their pigs the day before the slaughter team arrives. The animals should be slaughtered by methods that take account of animal welfare and the safety of operatives. Rifles or captive-bolt guns are most commonly used for pigs. The latter should not be used in confined areas where there is danger of ricochets. Lethal injections (e.g. barbiturates) may be used for unweaned pigs or pigs of any age if practical. If a captive-bolt weapon is used, operatives should take into account the fact that pigs may be stunned and not killed and use appropriate measures to ensure that animals are dead before burial or burning. Rifles should only be used by competent and experienced marksmen, to avoid compromising the safety of people and animals other than pigs.

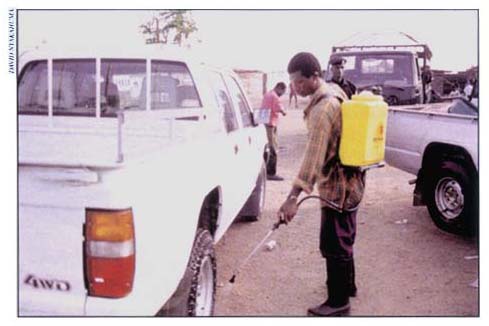

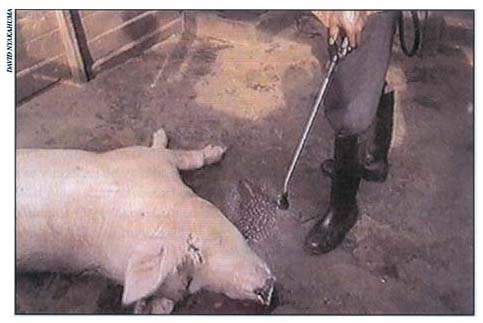

FIGURE 5

Disinfection

Thorough disinfection of vehicles is essential during an emergency disease outbreak to prevent

the disease from spreading to other premises.

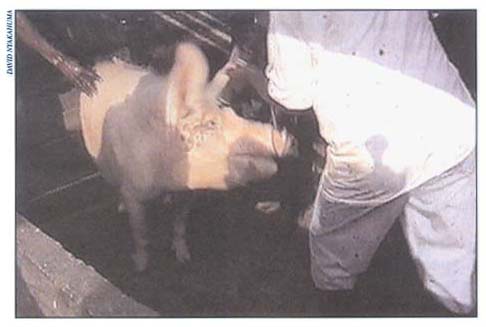

FIGURE 6

Humane killing

A stunner being used for humane killing of pigs during an ASF outbreak.

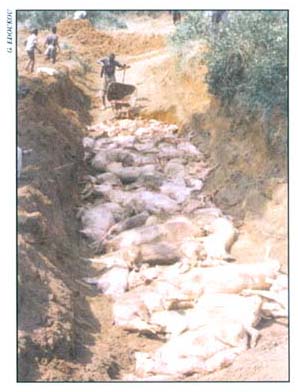

FIGURE 7

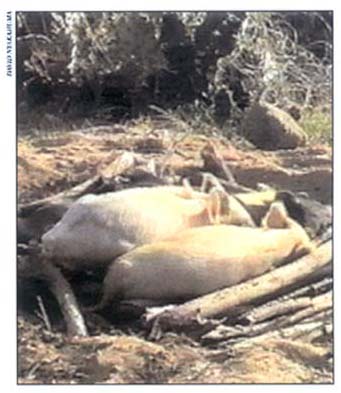

Deep burial

Deep burial is the recommended method of carcass disposal to ensure elimination of the virus from the environment.

FIGURE 8

Burning

Burning requires considerable skill to achieve effective results. In most cases the carcasses are not incinerated but merely roasted.

If pigs are poorly confined or are allowed to scavenge in the surrounding countryside, it may be necessary to send out teams of marksmen to locate and shoot them.

Reference should be made to the FAO Manual on procedures for disease eradication by stamping out for more information on slaughter procedures.

Safe disposal of carcasses

This means disposal of the carcasses of animals that have been slaughtered or died naturally of the disease. It must be done in such a way that the carcasses no longer constitute a risk for further spread of the pathogen to other susceptible animals by direct or indirect means, for example by carrion eaters, scavengers or through contamination of food or water. This is usually done by deep burial, depending on the nature of the terrain, level of watertables and availability of earth-moving equipment, or by burning, depending on availability of fuels and the danger of starting grass or bush fires. If in situ disposal is not practical, it may be possible to transport carcasses in sealed vehicles to a disposal point. This should be done within the infected zone. It is not ideal, especially in countries where sealed vehicles are not available and where vehicles in general are prone to breakdown. If it must be done, provision should be made for an escort vehicle to disinfect any leakages and initiate salvage operations should the vehicle transporting the pigs develop technical problems or be held up.

Under some circumstances it may be desirable to mount a guard at the disposal site for the first few days.

Reference should be made to the FAO Manual on procedures for disease eradication by stamping out for more information on disposal procedures.

Decontamination

This involves thorough cleaning and disinfection of the environs of IPs, with particular attention to places where animals have congregated - animal houses, sheds, pens, yards and water-troughs.

FIGURE 9

Disinfection

Disinfection is vital during the slaughter process to reduce the risk of contaminating the

environment with the ASF virus or other pathogens.

Potentially contaminated materials such as manure, bedding, straw and feedstuffs should be removed and disposed of in the same way as carcasses. It may be simpler to burn poorly constructed animal housing where there is a danger of Ornithodoros ticks. If ticks are absent, spraying with a disinfectant effective against ASF should be sufficient, as the virus does not remain viable for long outside a protein environment.

Appropriate disinfectants for ASF include 2 percent sodium hydroxide, detergents and phenol substitutes, sodium or calcium hypochlorite (2–3 percent available chlorine) and iodine compounds.

Reference should be made to the FAO Manual on procedures for disease eradication by stamping out for more information on decontamination procedures.

Destocking period

After slaughter, disposal and decontamination procedures must be completed and the premises left destocked for a period determined by the estimated survival time of the pathogen. As a general rule, this would be shorter in hot climates than in cold or temperate climates. A minimum of 40 days is recommended by OIE. A shorter period would probably be safe in tropical areas, because it has been shown that sties in such areas are safe for repopulation, even without cleaning or disinfection, after five days. In practice it is unlikely that definitive stamping out of a focus would be completed in less than 40 days.

The following disease-control actions should be undertaken in surveillance zones.

The emphasis in ASF-free zones is on preventing entry of the disease and accumulating internationally acceptable evidence that the zones are indeed ASF-free.

Entry of pigs or pig products from infected zones should be banned or only allowed subject to official permits from surveillance zones. Well managed, accredited pig farms in infected zones should be treated as if they were surveillance zones.

At the end of the agreed destocking period, pigs may be reintroduced to previously infected farms or villages. This should only be done, however, if there is reasonable certainty that these farms/villages will not be reinfected. Restocking to full capacity should only take place after sentinel pigs have been introduced at approximately 10 percent of the normal stocking rate on each previously infected farm. These pigs must be observed closely for six weeks to ensure they stay free of ASF before full repopulation. After repopulation, intense active surveillance for the disease should be maintained in the area at least until international declarations of freedom can be made.

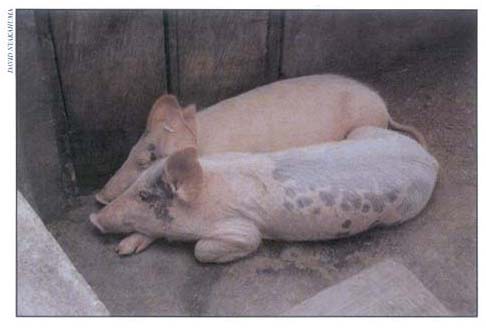

FIGURE 10

Sentinel animals

Sentinel animals require routine observation and examination to ensure that they are free of

ASF during the stand-down phase.

It is essential that pigs used for repopulation come from known ASF-free zones or countries. If pigs are imported from other countries, the disease status of those countries with respect to other important diseases of pigs must be known. It would be disastrous to replace ASF with another disease that might take many years and great expense to eradicate. The opportunity could be taken for upgrading pig genetic stocks in the area as part of the repopulation programme, provided the pigs are brought in from reliable sources such as local commercial farms that have remained uninfected.

Public awareness and education

Public-awareness and education campaigns should be important integral elements of the disease eradication campaigns. They should be mainly targeted at rural and peri-urban communities affected by the disease and ASF-control actions. Radio programmes and village meetings are the most appropriate means of getting the message across to these people. Meetings are particularly suitable, as there will be community involvement and the opportunity to ask questions and disseminate material such as pamphlets and posters that will reinforce the information.

FIGURE 11

Compensation

Scavenging pigs are hard to capture during stamping out, yet they are usually the major target

of the exercise. These pigs usually hide in forests and thick bushes when chased and nobody

claims ownership in such cases. An effective method of culling them in Togo and Ghana was to

mobilize village vigilante groups to hunt them. The carcasses were collected, disinfected if

necessary and disposed of by deep burial.

The campaign should inform people of the nature of the disease and what to do if they see suspect cases, what they can and cannot do during the eradication campaign and why and the benefits of getting rid of ASF. It should emphasize that ASF control primarily benefits pig producers and not the government.

Compensation

It is essential that farmers and others who have had their pigs slaughtered, pig meat products confiscated or property destroyed as part of an ASF eradication campaign should be fairly compensated with the current market value of the animals and goods. Compensation should be paid without delay. Valuation for compensation purposes should be undertaken by experienced, independent valuers. Alternatively, generic valuation figures could be agreed upon for categories of pigs, pig meat and other materials. At least the market value of the pigs should be paid. Under some circumstances, replacement of stock may be offered in lieu of monetary compensation.

Failure to pay adequate and timely compensation will seriously compromise ASF eradication campaigns by causing resentment and lack of cooperation. Such a failure would act as a spur to illegal smuggling and clandestine sale of pigs out of infected areas to avoid losses.

Social support and rehabilitation

An ASF-eradication campaign is likely to produce hardships for affected farmers and communities during the epizootic and the recovery phase. Consideration should therefore be given to government support to affected groups. There may be food shortages, particularly in infected zones, and it may be desirable to provide supplementation either in the form of pig meat or other types of animal protein from disease-free zones. Affected farming communities may need rehabilitation support to help them get back to normal at the end of the campaign. Assistance should be given to farms that have escaped infection but are unable to sell pigs because of bans on movement or closure of abattoirs and that have large numbers of pigs growing and eating on their farms. Where controlled slaughter is not a possibility, some assistance in the form of subsidized feed should be considered. It must be recognized that farmers who have avoided infection in the face of an epizootic are a national resource and should be rewarded rather than penalized.

International requirements

The OIE International animal health code specifies that a country may be considered free from ASF when it has been shown that ASF has not been present for at least three years. This period is reduced to 12 months, however, for previously infected countries in which a stamping-out policy is practised and in which it has been demonstrated that the disease is absent from domestic and wild pig populations.

A zone of a country may be considered free from ASF when the disease is notifiable in the whole country and when no clinical, serological or epidemiological evidence of ASF has been found in domestic or wild pigs in the zone during the past three years. This period will be 12 months for a previously infected zone in which a stamping-out policy is practised and in which it can be demonstrated that the disease is absent from domestic or wild pig populations.

The free zone must be clearly delineated. Animal-health regulations preventing movement of domestic or wild pigs into the free zone from an infected country or zone must be published and rigorously implemented. Regular inspection and supervision of pig movements should be made in the free zone to ensure freedom from ASF.

Proof of freedom

An internationally accepted protocol has not yet been established for verification and proof of freedom from ASF, unlike rinderpest, where there is an accepted OIE pathway for demonstration of disease freedom.

Evidence that could be provided to gain international acceptance of regained national ASF freedom might include documentation to show that:

Wild pig populations must have been examined for evidence of ASF infection. This could be done by shooting some animals in representative areas and examining tissues for ASF antigen and sera for antibodies. There is in most countries a hunting season, during which arrangements can be made to obtain carcasses of warthogs and other wild pigs shot for trophy purposes and meat. Serological evidence is sufficient proof of past infection, so where funds are available, bleeding tranquillized wild pigs would suffice.