According to the (Chinese) Provincial annals of livestock breeds, there are 12 officially recognized breeds of domestic yak in China: the Jiulong yak and Maiwa yak in Sichuan, Tianzhu White yak and Gannan yak in Gansu, Pali yak, Jiali ("Alpine") yak and Sibu yak in Tibet, Huanhu yak and Plateau yak in Qinghai, Bazhou yak in Xinjiang and Zhongdian yak in Yunnan, and one other, the "Long-hair-forehead yak" in Qinghai - which does not, however, meet all the criteria used to define a yak breed. Among these, the Plateau yak, Maiwa yak, Jiulong yak, Tianzhu White yak and Jiali ("Alpine") yak are also included in the publication Bovine breeds in China.

The yak of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau yak (often called Plateau or Grassland yak) and those of the Henduan mountain Alpine yak (often called Alpine or Valley yak) have long been regarded as "types". This classification was initially based on the geographic and topographic parameters of their habitats and on the body size of different yak populations in the different environments. Although there are some differences between the main types in appearance and in aspects of their performance - as there are also among the breeds - it is not yet resolved to what extent such differences are genetic and to what extent they derive from varying conditions in the areas in which these yak populations are found.

In this chapter, the main characters of 11 of the principal breeds are reviewed. In addition, information is given on an "improved" strain of yak, named Datong yak, which was started by crossbreeding between Huanhu yak and wild yak (using artificial insemination) and subsequently developed on the Datong Yak Farm in Qinghai. (The Datong yak is not at present classified as a breed because of its limited numbers).

Outside China, most notably in Mongolia and in countries of the CIS (formerly Soviet Union), yak are usually referred to by a name designating the area where they are kept or the area from which they have come. Whether this constitutes different breeds in the genetic sense is a matter for debate and is not generally claimed.

The yak was listed by Linnaeus (1766) as Bos grunniens, the same genus as other domestic cattle. However, in the middle of the nineteenth century the yak was listed as Poephagus grunniens (Gray, 1843) on the grounds of morphological distinctions from both other cattle and from bison. There was a return to Bos grunniens following Lydekker (1898), and this form has continued to be used to the present. More recently, however, the Poephagus classification has returned and been considered as the most appropriate for reasons discussed by Corbet (1978) and by Olsen (1990, 1991) following a re-examination of the available fossil evidence. The name Poephagus grunniens has been adopted increasingly, over recent years - but is by no means universally accepted. Clearly, this is a matter of considerable interest and concern to taxonomists. Since both the Bos and the Poephagus genera have their strong adherents in respect to the yak, it will be surprising if this debate ends anytime soon (see also Chapter 15 for new evidence favouring Poephagus). Fortunately, both camps agree on the species name of grunniens on account of the characteristic grunting noise made by the yak.

The yak has the same number of chromosomes (60) as Bos taurus and Bos indicus and interbreeds with both; the female hybrids being fertile and the male hybrids sterile. The yak will also interbreed with bison - again, the female hybrids are fertile, but not the males (Deakin et al., 1935). (These authors also report that the yak-bison hybrid showed stamina and speed to a "remarkable degree".)

Domestic yak differ from wild yak in being smaller and, not surprisingly, in temperament (see Chapter 1). It is not clear whether these differences have arisen because of differences in the selection pressures on wild and domestic yak or whether and to what extent genetic drift and inbreeding have contributed. However, there are many attributes in common between wild and domestic yak; broadly speaking, they share a similar environment and, as already noted, they will interbreed without difficulty, given the opportunity.

By crossing wild yak bulls with the Huanhu yak on the Datong Yak Farm, using artificial insemination, a "new" strain of yak has been developed (see section, A new strain of Datong yak in Qinghai). Moreover, the semen from the wild yak and semi-wild yak bulls have been extensively used with the intention of improving domestic yak productivity in Qinghai, Tibet, Sichuan, Gansu and Xinjiang (see Chapter 11, part 1). In former times, it was not uncommon for wild yak bulls to wander among domestic yak herds within their territory and mate with them (cf. Chapter 10). Crosses of wild and domestic yak and, consequently, their special qualities have been known for a long time to herdsmen in the vicinity of wild yak territory.

Twelve yak breeds were officially recognized by committees of yak experts on the basis of intensive investigations in the six main yak-raising provinces in China. Results of these deliberations published in the provincial annals of livestock breeds in the 1980s and discussed in many other publications (Lei Huanzhang, 1982; Editing Committee [Qinghai], 1983; Department of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine in Gansu, 1986; Editing Committee [Sichuan], 1987; Liu Zubo et al., 1989; Cai Li, 1989, 1992; Zhang Rongchang, 1989; Zhong Jincheng, 1996; Bhu Chong, 1998; Han Jianlin, 2000; Ji Qiumei, et al., 2002). The recognized breeds are the Jiulong yak and Maiwa yak in Sichuan, Tianzhu White yak and Gannan yak in Gansu, Pali yak, Jiali (Alpine) yak and Sibu yak in Tibet, Huanhu yak, Plateau yak and the "long-hair-forehead" yak in Qinghai, Bazhou yak in Xinjiang and Zhongdian yak in Yunnan. For this book's present purpose, the "long-hair-forehead yak" of Qinghai province is not considered further because it does not match the definition of a breed due to its random distribution in herds of both the Huanhu and Plateau yak. The remaining 11 breeds will be described here in some detail. However, all 11 breeds are distinguished only by origin, location and some small differences in productive characteristics (which might be attributable to the locality). There is almost no evidence available of the magnitude of any genetic differences.

The domestic yak of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (known as the Plateau or Grassland yak) and those of the Henduan mountain range (known as Alpine or Valley yak) in China have been regarded as "types" for a long time. This classification was initially based on the geographic and topographic parameters of their habitats and on the body size of the different yak populations (Cai Li, 1985). In 1982, a number of Chinese experts on the yak agreed to a broad classification of domestic yak into these two principal types (Plateau and Alpine) based on body conformation. The classification also took account of the ecological and social-economic conditions in which the yak were kept and evidence of any selection that had taken place. In general, it was thought that artificial selection applied to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau type during its development was less than that applied to the Henduan Alpine type (Cai Li, 1989).

Other classification suggestions have arisen from time to time but have not been subsequently adopted. Although there are some differences between the main types in appearance and in aspects of their performance - as there are among the breeds - it is not yet resolved to what extent such differences are genetic and to what extent they derive from the different conditions in the areas in which these yak populations are found. Even the once apparently clear distinction between the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the Henduan Alpine types has become blurred or ignored in recent literature.

To resolve the question of the relative contribution of heredity and environment to the apparent differences among the breeds of yak, one would require comparisons of them and of the crosses between them at the same location and at the same time. Better still, such comparisons should be repeated at a number of different locations typical of the different ecological habitats associated with the breeds of yak. If that were done, it might be expected that outward appearance associated with colour, hair and horn types and, to some extent, body conformation would remain largely distinct. However, differences in aspects such as body size and milk production, as well as reproductive performance, might converge in a common environment. But the extent of such effects cannot be predicted. Currently, genetic approaches using chromosomal and protein polymorphisms, mitochondrial DNA RFLP (restricted fragment length polymorphism), mitochondrial DNA sequencing and microsatellite genotyping are being introduced to the study of yak to estimate the genetic distance among breeds and some aspects of breed differentiation (see Chapter 15).

Plateau yak of Qinghai

This yak, now classified as a breed, is found on the cold highland pasture of southern and northern Qinghai province where the wild yak distribution overlapped with it, particularly in former times. Crossing between them is thus assumed to have taken place. Its population numbers around three million (Han Jianlin, 2000). The Plateau yak of Qinghai looks similar to the wild yak in body conformation. Among domestic yak breeds it stands tall, has a relatively large body weight and big head. Both sexes are horned. Similar to wild yak, it has greyish-white hair down its back and around the muzzle and eye sockets. It adapts well to the cold and humid climate at high elevation (see Table 2.1a). The majority of these yak are black-brown in colour (71.8 percent) and the rest are chestnut (7.8 percent), grey (6 percent), spotted (1.7 percent) and white (0.8 percent) (Lei Huanzhang, 1982; Editing Committee [Qinghai], 1983; Liu Zubo et al., 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Huanhu yak of Qinghai

This breed is found in the transitional zone around the Qinghai Lake in Qinghai province where the grasslands are predominantly semi-arid and consist of meadow pasture and neighbouring areas consist of dry Gobi and semi-Gobi pastures. It is believed that herds of this strain were domesticated and transferred to this area by the Qiang people, the predecessors of the present Tibetans, and by the Tufan people, beginning 10 000 years ago up through their later migrations. Around 310 A.D., Mongolian immigrants used Mongolian cattle to hybridize with the local yak to improve the relatively low productivity of the animals. Accordingly, the Huanhu yak, numbering about one million (Han Jianlin, 2000), contains some remnants of cattle blood from the time of its origins, and this may account for some of its differences from the Plateau yak (Liu Zubo et al., 1989). Compared to the Plateau yak, the Huanhu has a relatively smaller body size and finer structure, a wedge-shaped head, a narrower and longer nose that is mostly concave in the middle, a smaller but broad mouth, a thinner neck, deeper chest, narrower buttock, longer legs and smaller, but strong solid feet with a hard base to them. Most of the animals are hornless; those with horns have a fine, long and slightly curved set of horns. The colours are varied, but the majority is black-brown (64.3 percent); among the rest, there are grey animals (10.3 percent), white-spotted (10.7 percent) chestnut-brown (4.7 percent), white (3 percent) and other colours (6.9 percent) (Lei Huanzhang, 1982; Editing Committee [Qinghai], 1983; Liu Zubo et al., 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Tianzhu White yak of Gansu

The Tianzhu White breed (see Figure 2.1) is found in Tianzhu county of Gansu province, which is located in the eastern end of the Qilian mountains and the northern edge of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (102°02' - 103°29'E; 36°29' - 37°41'N). Its main distribution borders the Menyuan and Huzhu counties of Qinghai where a few white yak are also found. Generally, 2 - 3 percent of all yak populations are white individuals - though these are not regarded as part of the Tianzhu White breed. Because the white yak hair is easily dyed into different colours, it has been highly valued in local markets. On account of this, herdsmen who had migrated from Qinghai started to select and breed pure white herds about 120 years ago. A more intensive breeding programme started in 1981. Currently, there are around 60 000 of the white individuals (Liang Yulin and Zhang Haimin, 1998; Zhang Haimin and Liang Yulin, 1998). The breed has a medium body size and fine structure, a well-developed forepart but a less-developed rear part and strong but short legs. And there are big differences in size between the two sexes. Compared to the females, the males have larger heads with a wider forehead, longer and coarser horns with a visible contour, a larger mouth and broader muzzle, thinner lips, smaller nose and a coarser neck. The sex dimorphism is greater in the Tianzhu White yak than in other breeds. In the total population of the Tianzhu White breed in Gansu and Qinghai, around half the individuals have only white hair and skin with slightly red eye sockets. They are typical albinos. The rest are white but with coloured spots, mostly around the eye sockets. This colour helps to reduce problems to the eyes from the strong ultraviolet irradiation at high altitudes (Pu Ruitang et al., 1982; Department of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine in Gansu, 1986; Zhang Rongchang, 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Gannan yak of Gansu

Yak raising in the Gannan Tibetan autonomous prefecture of Gansu (100°46' - 104°45'E; 33°06' - 35°43'N), bordering Sichuan and Qinghai, for long has been based on the same yak from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Frequent exchange of breeding animals continues. There are about 700 000 animals of this breed (Han Jianlin, 2000). It has a strong body conformation and well-developed muscles, a relatively large skull, a short, wide and slightly protruding forehead, a long and concave nose with externally expanded muzzle, a square mouth with thin lips, horned (48 - 97 percent in different herds) or hornless, small ears, round eyes, a well-developed chest and belly and short, strong legs with small feet. Black is the predominant colour (76.8 percent of the animals); among the rest, the colours are white-spotted on black (15.8 percent), grey (6 percent) and yellow and white (1.4 percent). The males have longer and coarser horns with wider distance between the bases and a stronger neck than the females. The females have a small udder with short nipples (Department of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine in Gansu, 1986; Zhang Rongchang, 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Pali yak of Tibet

This breed is mainly found in Yadong county of Shigatse prefecture of the Tibetan Autonomous Region (approximately 88°8'E, 27°5'N), which borders western Bhutan and India. It has a strong and well-developed body conformation that is rectangular, a short skull with a wide forehead, a big round mouth with thin lips, small eyes, broad muzzle, small nose, a short, strong neck, a deep wide chest and large heart girth, a large belly and short, strong legs with small solid feet. Most of the animals have horns with wide bases. Black is the dominant body colour (87 percent); the rest are spotted black (11 percent) and brown (2 percent) (Tang Zhenyu et al., 1981; Liu Zubo et al., 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Sibu yak of Tibet

This breed is found in Medrogungkar county (approximately 92°40'E; 29°120'N) in the southeastern Lhasa municipality of Tibet. It has a large head with externally expanded horns, a rectangular-shaped body conformation with a straight back (Dou Yaozong et al., 1984; Liu Zubo et al., 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Jiali (Alpine) yak of Tibet

This breed is found in the Jiali (Lhari in Tibetan) county of the Nakchu prefecture (approximately 93°40'E; 31°N) of Tibet at the southern edge of the Nyenchen Thangla mountains. It has a relatively large body shape with a deep and wide chest, and it is mostly horned (83 percent). Compared to the females, males have coarser and stronger horns with a wide distance between the bases. Females have a thinner neck, straighter back, a larger belly and shorter legs than the males. Eighty percent of the animals have a white-spotted head or a completely white head. Half of them are white-spotted black, 41 percent are pure black or with only a white tail and the remaining 9 percent are white, brown or grey (NIAH et al., 1982; Liu Zubo et al. 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Jiulong yak of Sichuan

This breed (see Figure 2.2) belongs to the Jiulong county of Sichuan province, which is located on the southeastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (approximately 101°33'E, 28°39'N). It has a long history of development, but today's herds are the descendants of a relatively small population that survived a severe outbreak of Rinderpest some 150 years ago. The population now numbers around 50 000 animals (Zhong Jincheng, 1996; Lin Xiaowei and Zhong Guanghui, 1998). The Jiulong yak has a large body height and body size, with a deep and wide chest and a medium-sized head. The breed is horned. Males, compared to females, have a shorter head but with a wider forehead and wider-based horns, bigger eyes, thinner lips and well-developed teeth, a finer neck, straighter back and shorter legs. Females have a relatively long neck. Black is the predominant colour (61.7 percent); the rest are black-and-white (24.6 percent) and white-spotted on black (13.7 percent) (Editing Committee [Sichuan], 1987; Cai Li, 1989, 1992; Liu Zubo et al. 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Maiwa yak of Sichuan

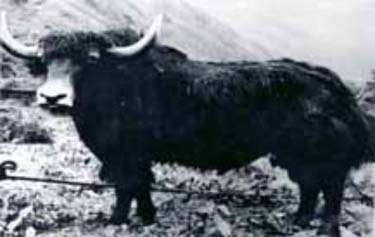

This breed (see Figure 2.3), numbering around 600 000 animals (Lin Xiaowei and Zhong Guanghui, 1998), belongs to Hongyuan county of Sichuan province (approximately 102°33'E; 32°48'N), which borders Gansu and Qinghai provinces The breed originated from almost the same locality as the present-day Jiulong yak. However, it was taken by a migratory tribe to its present habitat, passing through southern Qinghai, in the 1910s. During that migration, matings occurred with other domestic yak on route and with wild yak when it first settled in Hongyuan, when wild yak were still known to come down from Qinghai. The resulting infusions of genes are thought to have improved the original type. The better pasture and ecological environment of the new habitat assisted its development. It has a medium-sized head and a wide flat forehead, straight back, a well-developed belly, a long body with short legs and small solid feet. Most of the animals are horned. Black accounts for 64.2 percent of the population's colouring; the rest are black with a white-spotted head and tail (16.8 percent), cyan (a very dark blue) (8.1 percent), brown (5.2 percent), black-and-white (4.2 percent) or other colours (1.5 percent) (Cai Bolin, 1981; Editing Committee [Sichuan], 1987; Cai Li, 1989, 1992; Liu Zubo et al. 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Bazhou yak of Xinjiang

This breed is found mainly in Hejing county (83° - 93°56'E, 36°11' - 43°20'N) in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Their presence dates to 1890 when around 60 animals were brought from Tibet (Zhou Yiqing, 1980); another 176 animals were introduced in 1920 (Dong Baoshen, 1986). In the late 1980s, some breeding bulls were purchased from the Datong Yak Farm in Qinghai to refresh the blood (Dong Baoshen, 1986). There are now about 70 000 Bazhou yak (Fang Guangxin and Liu Wujun, 1998). This breed has a large rectangular body, a heavy head, a short and wide forehead, big round eyes, small ears, a broad muzzle and thin lips, a wide chest, large belly and strong legs with small, solid feet. The majority (77.3 percent) have fine, long horns. Black is the main colour, but some are black and white, brown or grey and white (Gala et al., 1983; Yu Daxin and Qian Defang, 1983; Zhang Rongchang, 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

Zhongdian yak of Yunnan

This breed is found in the Zhongdian and Deqin counties (99°50' - 100 50'E, 26°85' - 28 40'N) in the very northern part of Yunnan province, at the southern end of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau where it borders Tibet and Sichuan. In general, the Zhongdian yak has had frequent exchanges of blood with yak in Sichuan. There are about 20 000 animals of this breed (Zhong Jincheng, 1996; Han Jianlin, 2000). It has a strong body conformation, large round eyes, small ears, a wide forehead, a deep chest, straight back, well-developed legs with large feet and a short tail. Both sexes have horns. There is relatively large variation in body size. The majority of the animals are black (62.4 percent), a black-and-white colouring is found among 27.5 percent of them, while the rest are black with white-spots on the forehead, legs and tail (Liu Guoliang, 1980; Duan Zhongxuan and Huang Fenyin, 1982; Zhang Rongchang, 1989). Their productivity is shown in Table 2.1b.

A new strain of Datong yak in Qinghai

This is the only improved yak population developed deliberately by crossing wild yak bulls with domestic yak females with the intention of creating a new breed of yak. The development is taking place on the Datong Yak Farm in Qinghai (approximately 101°70'E, 32°N and at an altitude of around 3 200 m). For this purpose, one wild yak bull captured in the Kunlun mountains and two in the Qilian mountains (with an altitude of more than 5 000 m) were taken to Datong Yak Farm and trained for semen collection between 1983 and 1986.

Figure 2.1 Tianzhu White yak (Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau type)

Figure 2.2 Jiulong yak (Henduan Alpine type) a) male

Figure 2.2 Jiulong yak (Henduan Alpine type) b) female

Figure 2.3 Maiwa yak (Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau type) a) male

Figure 2.3 Maiwa yak (Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau type) b) female

The semen of these three bulls is used to artificially inseminate the Huanhu yak cows. To date this has produced 1 086 crossbred animals (F1), which formed the foundation generation. Then six F1 breeding bulls were selected from that group. The next generation consisted of 1 700 breeding cows, which were of both the F2 type (from mating F1 females to F1 males) and back-crosses (B1) (from mating F1 males with the domestic yak females). The subsequent generation (designated the second generation in the programme) of 29 breeding bulls and 542 breeding cows was obtained by mating B1 to each other, F1 males with the B1 females and B1 males with the F1 females. That generation, in turn, was used to create a nucleus herd. A third generation was created by intermating the offspring from the second generation. In a similar way, a fourth generation was produced from the third. By the year 2000, there were about 2 000 animals in the nucleus herd at the Datong Yak Farm where most performance records have been taken and where most of the selection was practiced. A further 20 000 animals in multiplier herds were situated at three locations: the Datong Yak Farm in Qinghai and the Shandan and Liqiaru farms in Gansu. The animals in the multiplier herds derived from the third and fourth generations at the Datong Yak Farm. In total, 8 700 breeding animals, from the foundation to the third generation, had their productivity recorded over a 15-year period.

The objective in the nucleus herd was to control inbreeding and to select breeding bulls to improve yak productivity. The average inbreeding coefficient was estimated as 0.094 (0.031 - 0.125). The selection of bulls was made first around the time of birth using their own birth weight (adjusted for the parity of the dam) and the body conformation, birth weights and growth of their parents. Ten percent of the bulls were discarded at this stage. A second selection took place when the bull calves were six months old. Body weight and conformation before winter were considered, and weight was adjusted for parity and month of calving. Between 30 and 50 percent of the bull calves were rejected at that stage. A third selection was conducted at age 18 months. This was regarded as a particularly important time for further selection as the animals were weaned and had had the opportunity to express their performance, in terms of growth and body conformation, under both a harsh winter season and the following summer season with adequate nutrition. Sixty percent of those so evaluated were rejected from further consideration. A final selection was made when the animals were between two and a half and three and half years old. At this time, the bulls were each mated to between 15 and 20 cows to check for their reproductive capacity and the offspring phenotype of potential replacement bulls. Each bull's own growth and body conformation was also reconsidered. Half of the bulls taking part at this stage were discarded. After these four selections, around 11 percent of the original group remained for use as replacement breeding bulls.

The Datong yak looks not dissimilar to the wild yak with its greyish-white mouth, nose, sockets and grey back line. The males are horned and females are either horned or hornless. The body conformation seems to be of a meat type with good body weight, straight back, a wide chest, and long, strong legs. The body colour is typically black, though there may also be a few brown hairs. The body measurements and the selection progress of the Datong yak are shown in Tables 2.2 and 2.3. In addition, the milk and fibre yields of the Datong yak were recorded and compared with the Huanhu yak and are reported in a number of publications (Bo Jialin et al., 1998a, b; Wang Minqiang et al., 1998).

Not surprisingly in view of the relative isolation of different areas from each other, at least in times past, many distinct breeds of yak have developed in China. Five of them are listed as breeds at national level in the Bovine breeds of China (Institute of Animal Science [China], 1986). These are the Plateau yak, Maiwa yak, Jiulong yak, Tianzhu White yak and Jiali (Alpine) yak. The Provincial Administration of Standardization in both Gansu and Sichuan also issued breed criteria for the Maiwa yak, the Jiulong yak and the Tianzhu White yak (TAHVS and DAS, 1985; Zhong Guanghui et al., 1995; Wen Yongli et al., 1995).

Some information on the various breeds is shown in Tables 2.1a and 2.1b. Three of the breeds are shown in Figures 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3.

From the available literature, it appears that yak in most countries outside China are not specifically classified as "breeds". Instead, they are referred to as yak of a particular area in which they are found or from which they have been brought, or they may take their name from the people of the area. For example, Sarbagishev et al. (1989) referred in this manner to the yak in various parts of the former USSR: "Yaks bred in Kirgizia are considerably larger than those in Tajikistan." They are careful to note a management difference between these two populations of yak so as not to draw the conclusion that the differences are necessarily genetic. In the same manner, Zagdsuren (1994) referred to the country of origin when discussing hybridization of yak with cattle of other species. Smirnov et al. (1990) referred to yak of "Tuva type" when writing about meat production trials in the northern Caucasus. Verdiev and Erin (1981) referred to Pamir, Altai and Buryatia types, which are the names for the areas or country where the yak are located. In writing about domestic livestock in Nepal, Epstein (1977) also did not separate yak into breeds. It thus appears that differences among "local" populations of yak are recognized, but whether these constitute different breeds, in the genetic sense, is a matter for further investigation. Pal et al. (1994) classified the yak of India into a number of types, as described in the section on India in Chapter 11, part 2. For further general information on yak in other countries, see also Chapter 11.

Table 2.1a Main breeds of yak in China and observations on distribution and characteristics

[Source: adapted and revised from Cai Li, 1985]

|

Location (province or autonomous region) |

Breed |

Main area |

No. ('000) |

Topography |

Pasture type |

Grass type (predominant type) |

Altitude (m) |

Average annual temp. (°C) |

Rainfall (mm) |

|

Sichuan |

Jiulong* |

Jiulong county and Shade district of Kangding county in Ganzi Tibetan autonomous prefecture |

30 |

High mountain intersecting valleys |

Alpine bush and meadow |

Mixed sward |

>3 500 |

2.0 |

900 |

|

Maiwa* |

Hongyuan and Ruoergai counties in Aba Tibetan and Qiang autonomous prefecture |

200 |

Hill-shaped plateau |

Cold meadow and marsh |

Gramineae, cyperaceae |

3 400-3 600 |

1.1 |

728 |

|

|

Yunnan |

Zhongdian |

Zhongdian county in Diqing Tibetan autonomous prefecture |

|

Hill-shaped plain among mountains |

Alpine bush and meadow |

Mixed sward and grass |

3 276 |

5.4 |

620 |

|

Gansu |

Tianzhu White* |

Tianzhu Tibetan autonomous county |

30 |

Broad plateau and valley |

Sub-alpine meadow |

Many bush on n. slopes; Gramineae Cyperaceae |

[3 000] |

0.1 |

300-416 |

|

Gannan |

Gannan Tibetan autonomous prefecture |

|

Hill-shaped plateau |

Alpine and sub-alpine |

Gramineae, Cyperaceae |

3 300-4 400 |

0.4 |

664 |

|

|

Qinghai |

Plateau* |

Northern and southern Qinghai |

3 400 |

Plateau |

Alpine meadow |

Gramineae, Cyperaceae |

3 700-4 700 |

From -2 to -5.7 |

282-774 |

|

Huanhu |

Mountainous region around the Qinghai Lake |

|

Mountain |

Sub-alpine meadow, part forest grassland |

Grass |

2 000-3 400 |

From 0.1 to 5.1 |

269-595 |

|

|

Tibet |

Jiali (Alpine)* |

Alpine area of Tibet; Jiali county |

1 400 |

Plateau, mountain |

Alpine bush and meadow |

Mixed sward |

>4 000 |

0 |

694 |

|

Pali |

Yadong county |

|

Plateau, mountain |

Alpine meadow |

Gramineae, Cyperaceae |

4 300 |

1.7 |

468 |

|

|

Sibu |

Medrogungkar county |

|

Plateau, mountain |

Alpine bush and meadow |

Mixed sward |

4 000-5 500 |

0 |

700 |

|

|

Xinjang |

Bazhou |

Centre of Tianshan mountains |

|

Mountain |

Sub-alpine meadow |

Grass |

2 400 |

-4.7 |

285 |

* Listed as national breeds in China. ** Estimated body weight = {(heart girth [m])2 x (body length [m]) x 70}.

Table 2.1b Main breeds of yak in China and observations on distribution and characteristics

| |

Breed |

Sex |

No. |

Body measurements (cm) |

Body weight** (kg) |

Source |

|||

|

Height at withers |

Body length |

Heart girth |

Cannon bone circumference |

||||||

|

Sichuan |

Jiulong* |

M |

15 |

138 |

178 |

219 |

23.6 |

594 |

GAAHB and YRO, 1980a, b; Cai Li, 1989 |

|

F |

708 |

117 |

140 |

179 |

18.2 |

314 |

|

||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Maiwa* |

M |

17 |

126 |

157 |

193 |

19.8 |

414 |

Cai Li, 1989 |

|

|

F |

219 |

106 |

131 |

155 |

15.6 |

222 |

|

||

|

Yunnan |

Zhongdian |

M |

23 |

119 |

127 |

162 |

17.6 |

235 |

Duan Zhongxuan and Huang Fenying, 1982 |

|

F |

186 |

105 |

117 |

154 |

16.1 |

193 |

|

||

|

Gansu |

Tianzhu White* |

M |

17 |

121 |

123 |

164 |

18.3 |

264 |

Pu Ruitang et al., 1982; Zhang Rongchang, 1989 |

|

F |

88 |

108 |

114 |

154 |

16.8 |

190 |

|

||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Gannan |

M |

10 |

126 |

141 |

189 |

22.4 |

354 |

Department of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine in Gansu, 1986; Zhang Rongchang, 1989 |

|

|

F |

159 |

109 |

122 |

157 |

16.1 |

210 |

|

||

|

Qinghai |

Plateau* |

M |

21 |

129 |

151 |

194 |

20.1 |

398 |

Editing Committee [Qinghai], 1983 |

|

F |

208 |

111 |

132 |

157 |

15.8 |

228 |

|

||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Huanhu |

M |

14 |

114 |

144 |

169 |

18.3 |

287 |

Editing Committee [Qinghai], 1983 |

|

|

Tibet |

Jiali (Alpine)* |

M |

8 |

130 |

154 |

197 |

22.4 |

421 |

NIAH et al., 1982; Liu Zubo et al., 1989 |

|

F |

187 |

107 |

133 |

162 |

16.1 |

243 |

|

||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Pali |

M |

59 |

111 |

123 |

155 |

18.3 |

288 |

Tang Zhenyu et al., 1981; Liu Zubo et al., 1989 |

|

|

F |

321 |

109 |

121 |

152 |

15.2 |

217 |

|

||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Sibu |

M |

4 |

132 |

149 |

185 |

21.0 |

358 |

Dou Yaozong et al., 1984; Liu Zubo et al., 1989 |

|

|

F |

53 |

109 |

127 |

153 |

15.9 |

212 |

|

||

|

Xinjiang |

Bazhou |

M |

33 |

127 |

140 |

192 |

20.7 |

359 |

Dong Baoshen, 1986 |

|

F |

265 |

111 |

124 |

171 |

16.3 |

257 |

|

||

* Listed as national breeds in China. ** Estimated body weight = {(heart girth [m])2 x (body length [m]) x 70}.

Table 2.2 Body measurements and weights of the first generation Datong yak in comparison to the Huanhu yak on the Datong Yak Farm [Source: Bo Jialin et al., 1998b]

|

Group |

No. |

Age (month) |

Height at withers (cm) |

Body length (cm) |

Heart girth (cm) |

Cannon bone circumf. (cm) |

Body weight (kg) |

|

Datong yak |

7a |

6 |

88.4 ± 5.6 |

87.1 ± 5.2 |

106.8 ± 4.8 |

12.0 ± 0.7 |

74.7 ± 10.4 |

|

Huanhu yak |

7 |

6 |

79.4 ± 3.4 |

52.0 ± 4.6 |

96.4 ± 5.1 |

11.3 ± 1.1 |

58.8 ± 10.2 |

|

Difference |

|

|

5.1* |

5.1* |

10.4** |

0.7 |

14.88** |

|

Datong yak |

7 |

18 |

103.1 ± 2.4 |

108.5 ± 4.7 |

141.6 ± 4.7 |

14.6 ± 0.9 |

150.5 ± 56.1 |

|

Huanhu yak |

7 |

18 |

100.1 ± 3.5 |

103.2 ± 2.8 |

131.3 ± 4.5 |

13.7 ± 0.4 |

117.7 ± 17.4 |

|

Difference |

|

|

2.7* |

5.3* |

10.3** |

0.9 |

32.8** |

Note: * P<0.05; ** P<0.01. a: Pooled data from 4 females and 3 males of both groups.

Table 2.3 Generation progress of body weights of animals in the nucleus herd at the Datong Yak Farm (data from males [M] and females [F] pooled) [Source: Wang Minqiang et al., 1998]

|

Item |

Generation 0 |

1st generation |

2nd generation |

|

Birth weight |

11.49 ± 0.98 |

12.04 ± 0.89 |

12.42 ± 0.89 |

|

No. |

10 M and 11 F |

12 M and 15 F |

14 M and 19 F |

|

Weight at 6 months |

71.02 ± 7.80 |

74.71 ± 10.47 |

82.19 ± 12.91 |

|

No. |

10 M and 15 F |

4 M and 3 F |

12 M and 19 F |

|

Weight at 18 months |

135.08 ± 10.18 |

150.50 ± 6.07 |

154.40 ± 11.18 |

|

No. |

8 M and 12 F |

9 M and 12 F |

8 M and 12 F |

References

Bhu Chong (1998). Present situation of research and production of yak husbandry in Tibet. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 38-40.

Bo Jialin et al. (1998a). Raising of the Datong new yak breed. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 9-13.

Bo Jialin et al. (1998b). Meat production performance from generation Datong yak in China. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 15-18.

Bo Jialin et al. (1998c). Milk production from one generation Datong yak in China. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 19-20.

Cai Bolin (1981). Introduction to the Maiwa yak. Journal of China Yak, 1: 33-36.

Cai Li (1985). Yak breeds (or populations). In Chen Pieliu (ed), Domestic animal breeds and their ecological characteristics in China. Beijing, China Agricultural Press pp. 45-59.

Cai Li (1989). Sichuan yak. Chengdu, China, Sichuan Nationality Press. 223 pp.

Cai Li (1992). China yak. Beijing, China Agriculture Press. 254 pp.

Corbet, G.B. (1978). The mammals of the Palaearctic Region: a taxonomic review. British Museum (Nat. Hist.), Ithaca, New York, Cornell Univ. Press. 314 pp.

Deakin, A., Muir, G.W. & Smith, A.G. (1935). Hybridisation of domestic cattle, bison and yak. Report of Wainwright experiment. Publication 479, Technical Bulletin 2, Dominion of Canada, Department of Agriculture, Ottawa.

Department of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine in Gansu (1986). Annals of livestock and poultry breeds in Gansu. Lanzhou, China, Gansu People's Press.

Dong Baoshen (1986). Source, economic traits and development of Hejing yak. Journal of China Yak, 2: 33-37.

Dou Yaozong et al. (1984). Tibetan yak. Journal of Tibetan Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine, 2: 12-34.

Duan Zhongxuan & Huang Fenying (1982). Report of survey on the Zhongdian yak. Journal of China Yak, 1: 75-82.

Editing Committee [Qinghai] (1983). Annals of livestock and poultry breed in Qinghai. Xining, China.

Editing Committee [Sichuan] (1987). Annals of livestock and poultry breeds in Sichuan. Chengdu, China, Sichuan Scientific and Technology Press.

Epstein, H. (1977). Domestic animals of Nepal. New York, Holmes & Heier. pp. 20-37.

Fang Guangxin & Liu Wujun (1998). Present situation, constraints and future actions of yak husbandry in Xinjiang. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 50-51.

GAAHB (Ganzi Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Bureau) and YRO (Yak Research Office of Southwest Nationalities College) (1980a). The good meat-purpose yak - the investigation and study of Jiulong yak. Journal of China Yak, 1: 14-33.

GAAHB (Ganzi Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Bureau) and YRO (Yak Research Office of Southwest Nationalities College) (1980b). The general survey and identification for Jiulong yak. Journal of China Yak, 3: 17-24.

Gala, Mao Guangtong et al. (1983). Bazhou yak in Xinjiang. Journal of China Yak, 2: 46-50.

Gray, J.E. (1843). List of mammals in the British Museum. London, British Museum.

Han Jianlin (2000). Conservation of yak genetic diversity in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region and central Asian steppes. In Shrestha, J.N.B. (ed), Proceedings of the fourth global conference on conservation of domestic animal genetic resources, in Kathmandu, 17-21 August 1998. pp. 113-116.

Institute of Animal Science [China] (1986). Bovine breeds in China. Shanghai, China, Shanghai Scientific and Technology Press. pp. 117-132.

Ji Qiumei et al. (2002). Resources of yak production in Tibet and reasons for the degeneration of productive performances. Proceedings of the third international congress on yak, in Lhasa, China, 4-9 September 2002. Nairobi, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). pp 300-307.

Lei Huanzhang (1982). Discussion of types and utilization of Qinghai yak. Journal of China Yak, 2: 1-3.

Liang Yulin & Zhang Haimin (1998). Conservation and utilization of Tianzhu White yak. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 56-57.

Linnaeus, C. (1766). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis synonymis, locis. Vol 1, Regnum Animale, pt. 1, pp. 1-532.

Lin Xiaowei & Zhong Guanghui (1998). Present situation and development strategy of yak husbandry in Sichuan. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 26-28.

Liu Guoliang (1980). Zhongdian yak. Journal of China Yak, 2: 75-82.

Liu Zubo, Wang Chengzhi & Chen Yongning (1989). Yak resources and qualified populations in China. In Chinese Yakology. Chengdu, China, Sichuan Scientific and Technology Press. pp. 36-77.

Lydekker, R. (1898). Wild Oxen, sheep and goats of all lands. London, Rowland Ward Ltd. 314 pp.

NIAH (Nagqu Institute of Animal Husbandry), Jiali Farm and Jiali Veterinary Station (1982). Report of investigation of the Jiali yak. Journal of China Yak, 3: 51-56.

Olsen, S. J. (1990). Fossil ancestry of the yak, its cultural significance and domestication in Tibet. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 142: 73-100.

Olsen, S.J. (1991). Confused yak taxonomy and evidence of domestication. Illinois State Museum Scientific Papers, Vol. 23: 387-393.

Pal, R.N., Barari, S.K. & Basu, A. (1994). Yak (Poephagus grunniens L.), its type - a field study. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, 64: 853-856.

Pu Ruitang, Zhang Rongchang, Zhao Yiner & Den Shizhang (1982). Introduction to the Tianzhu White yak. Journal of China Yak, 1: 64-74.

Sarbagishev, B.S., Rabochev, V.K. & Terebaev, A.I. (1989). Yaks. In Dmitriev N.G. & Emst, L.K. (ed), Animal genetic resources of the USSR. FAO Animal Production and Health Paper, No. 65, Rome. pp. 357-364.

Smirnov, D.A. et al. (1990). Meat yield and meat quality of yaks. Sel'skokkhozyaistvennykh Nauk Im. V.I. Lenina. (Soviet Agricultural Sciences), No. 1: 46-49.

TAHVS (Tianzhu Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Station) and DAS (Department of Animal Science of Gansu Agricultural University) (1985). Breed criterion of the Tianzhu White yak in Gansu Province (Gan Q/NM4-85). Issued by Provincial Administration of Standardization on 2 January 1985 and effective 1 April 1985.

Tang Zhenyu et al. (1981). Survey of the yak in Pali district of Yadong county in Tibet. Journal of China Yak, 2: 46-50.

Verdiev, Z. & Erin, I. (1981). Yak farming is milk and meat production. Molochnoe I miasnoe skotovodstvo, 2: 16-17.

Wang Minqiang et al. (1998). Selection and breeding for bulls and the generation progress of the mass breeding in raising of the Datong new yak breed. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 13-15.

Wen Yongli et al. (1995). Breed criterion of the Maiwa yak in Sichuan Province (DB51/249-95). Issued by Provincial Administration of Standardization on 14 December 1995 and effective 1 January 1996.

Yang Bohui et al. (1998). Study on the fair and underwool production of Datong yak. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 21-23.

Yu Daxin & Qian Defang (1983). General situation of Xinjiang yak. Journal of China Yak, 1: 57-64.

Zagdsuren, Yo (1994). Heterosis in yak hybrids. Proceedings of the first international congress on yak. Journal of Gansu Agricultural University (Special issue June 1994). pp. 59-62.

Zhang Haimin & Liang Yulin (1998). Survey on herd structure and management of Tianzhu White yak. Forage and Livestock, Supplement: 57-58.

Zhang Rongchang (1989). China: the yak. Lanzhou, China, Gansu Scientific and Technology Press. 386 pp.

Zhong Guanghui et al. (1995). Breed criterion of the Jiulong yak in Sichuan Province (DB51/250-95). Issued by Provincial Administration of Standardization on 14 December 1995 and effective 1 January 1996.

Zhong Jincheng (1996). Yak genetics and breeding. Chengdu, China, Sichuan Scientific and Technology Press. 271 pp.

Zhou Yiqing (1980). Brief introduction to the Hejing yak in Xinjiang. Journal of China Yak, 1: 91.