Avian influenza is a viral disease of several avian species in various parts of the world. The disease can range from asymptomatic and mild to hyperacute and fatal. Avian influenza occurs infrequently in humans. It is seen as an occupational hazard, primarily to those associated with varied activities in the poultry industry; employees in abattoirs, vaccinators, laboratory staff and other personnel. In most cases the clinical picture is that of conjunctivitis with rare systemic reactions. Avian influenza is reportable disease in many countries. It has to be confirmed by virus isolation.

Transmission : Secretions from infected birds, by wild birds and contaminated feed, equipment and people. Seabirds and migratory waterfowl comprise the main reservoir for avian influenza virus.

Antemortem findings:

Postmortem findings :

Mild to moderate infection

Judgement : Carcasses affected with avian influenza in any form should be condemned.

Differential diagnosis : Fowl cholera, chlamydiosis, mycoplasmosis, velogenic viscerotropic Newcastle disease

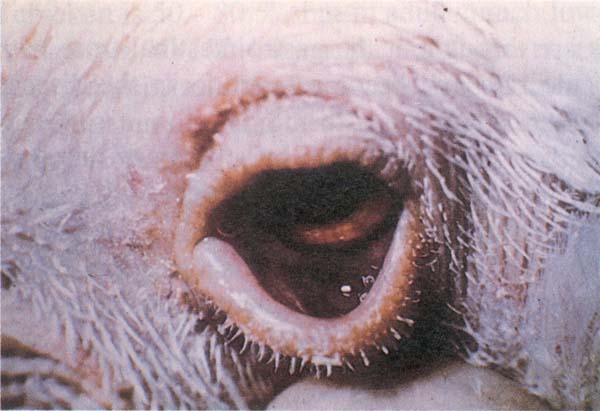

Fig. 187: AI. Edematous, cyanotic comb and wattles of a chicken.

Fig. 188: Bloody cloaca and dark coloured skin of a chicken that died of AI.

Fig. 189: AI. Haemorrhage in the small intestine, between two dark coloured ceca.

Velogenic Viscerotropic Newcastle disease (VVND) or Asiatic Newcastle disease (AND)

NCD is in its chronic form an infection of domestic fowl with symptoms such as rejection of food, listlessness, abnormal breathing, discharge from eyes and greenish diarrhoea. Mortality in chicken is 50 – 80 %, but in adults much lower due to available vaccination. VVND is an acute, fatal infection of birds of all ages with predominant haemorrhagic lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, severe depression, and death prior to clinical manifestations. This disease is caused by the most virulent strain of the Newcastle disease virus. The virus of VVND is very resistant and remains viable at extreme pH and temperature ranges, and may remain viable in the bone marrow of poultry carcasses for weeks.

Transmission : Transmission is by direct contact, fomites, and by aerosols through coughing, gasping and respiratory fluids. The virus has a wind borne potential for spread creating quite a challenge for control and prevention. Faeces and insect and rodent vectors are also involved in the transmission.

Antemortem findings :

Postmortem findings :

Acute form

Chronic form

Judgement : Birds with VVND or NCD should not be admitted to the abattoir. If disease is suspected laboratory confirmation should be obtained. If confirmed, carcass is condemned and premises with equipment should be disinfected. In case that laboratory confirmation is not possible, suspected carcasses should be also condemned. In some countries compensation is paid for condemned birds.

Differential diagnosis : VVND and NCD must be differentiated from the following diseases: Infectious bronchitis, laryngotracheitis, fowl cholera, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), fowl pox (diphtheritic form), psittacosis, acute Mycoplasma gallisepticum infection, avian encephalomyelitis, vitamin E deficiency, Marek's disease and Pacheco's disease in parrots

Fig. 190: New Castle disease (NCD). Swelling of the lower eyelid and conjunctivitis.

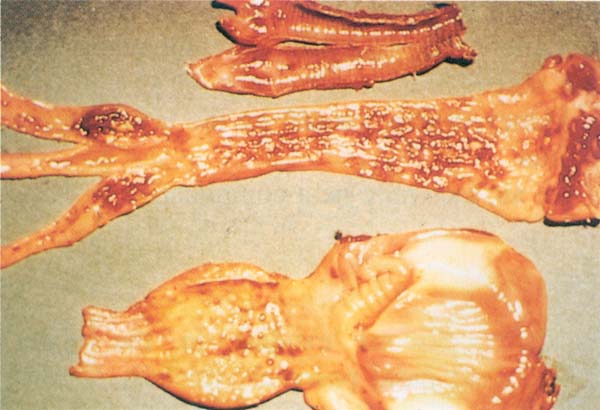

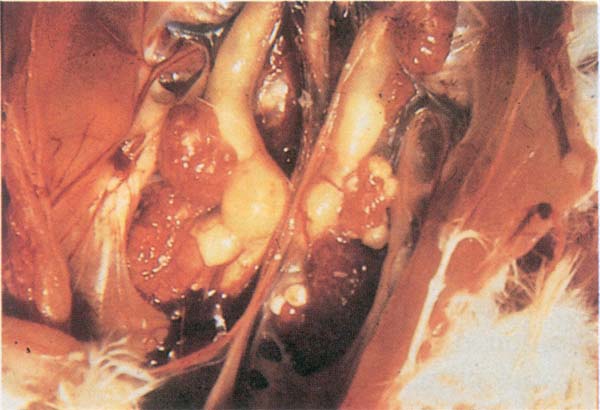

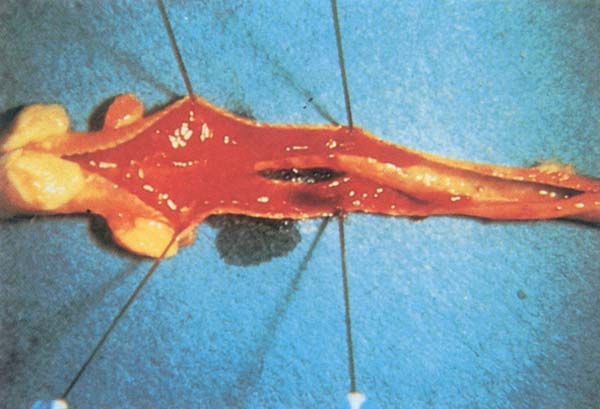

Fig. 191: NCD. Acute form: Haemorrhage in the mucosa of the trachea (upper), large intestine, particularly caecal tonsils (middle), proventriculus (bottom) and gizzard.

Infectious bronchitis is an acute, highly contagious viral disease of chickens, manifested by respiratory signs, renal disease and a significant drop in egg production.

Transmission : Airborne transmission in the direction of prevailing wind. The spread of infection is rapid in a flock. Some birds become carriers and shedders of the virus through secretions and discharges for many months after the infection. IB virus persists in contaminated chicken houses for approximately four weeks.

Antemortem findings:

Postmortem findings:

Judgement: Affected birds are treated as suspects on antemortem inspection. A carcass showing acute signs of clinical disease accompanied with emaciation is condemned. A carcass in good flesh and without systemic changes is approved. The affected parts are condemned.

Differential diagnosis: Newcastle disease, laryngotracheitis (LT) and infectious coryza. Laryngotracheitis spreads slowly in a flock although respiratory signs are more severe than in infectious bronchitis. LT is not seen in young chicken.

Fig. 192: IB. Abdominal airsac containing yellowish caseous exudate.

Fig. 193: IB. Swollen kidneys and ureters containing urolith deposits (uric acid crystals).

LT is an acute viral disease of chicken characterized by difficult breathing, gasping and coughing up of bloody exudate.

Transmission: Virus entry in LT is via the respiratory route and the intraocular route. Oral infection may also occur. The transmission from acutely infected birds is more common than from recovered or vaccinated birds. The latter may shed the virus for a prolonged period of time. Mechanical transmission via fomites is another possibility.

Antemortem findings:

Most chicken usually recover in 10 –14 days and up to 4 weeks in severe cases.

Postmortem findings:

Judgement: Mild form of disease and recovered birds may have a favourable judgement if carcass is in good flesh. If an acute condition is associated with general systemic changes, the carcass is condemned.

Differential diagnosis : Newcastle disease, Infectious bronchitis and infectious coryza

Fig. 194: LT. Difficult breathing and coughing.

Fig. 195: LT. Inflamed trachea containing cheesy plugs.

Fowl Pox is a viral disease of chicken, turkeys and other birds distinguished by cutaneous lesions on the head, neck, legs and feet. It has a worldwide distribution and affects birds of all age groups, except the recently hatched.

Transmission : The virus is present in lesions and in desquamated scabs. It is resistant to environmental factors and persists in the environment for many months. It usually infects birds through minor abrasions. Mechanical transmission occurs by cannibalism. Some mosquitoes can transmit the virus from infected to uninfected birds. The virus can be also transmitted by injury to the skin.

Antemortem findings: Two forms of lesions are recognized, - the cutaneous (dry form) and the diphtheric (wet form)

Cutaneous form

Diphtheric form

Postmortem findings: The following stages of the pox lesions papules, vesicles and pustules may be observed.

Cutaneous lesions

Diphtheric lesions

Histopathology shows characteristic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Bollinger bodies) in the infected epithelium.

Judgement : Carcass affected with fowl pox is condemned if progressive generalized lesions in a bird are accompanied with emaciation. Fowls with localized lesions and recovered birds are approved after the removal of scales.

Differential diagnosis : Pantothenic acid and biotin deficiency, vitamin E deficiency, infectious laryngotracheitis and other respiratory diseases in poultry, injuries caused by external parasites and cannibalism.

Fig. 196: FP. Cutaneous form (dry pox). Face lesions in young turkey.

Fig. 197: FP. Diphtheric form (wet pox). Caseous lesions in the mouth and throat of a chicken.

Avian leucosis complex

Transmission : L/S virus is transmitted by egg in vertical transmission and by shedders in horizontal transmission (chicken to chicken). Tumour lesions may or may not develop. Developed tumours can be differentiated by the bird's age on necropsy, histology and impression smears. In horizontal transmission, chicken which contract the virus after hatching develop antibodies; some will remain shedders, some will develop tumours and die, and others will overcome the infection. Infection from flock to flock is unlikely as the virus does not survive a long time in the environment. In many chickens the virus may be also in a latent state.

This disease is being studied because of its economic significance, and also as an experimental model of cancer. Lymphoid leucosis is a B cell tumour which starts in the bursa and, before sexual maturity, may spread to other organs. Mature birds are more affected than young birds. Male birds are also affected in lesser numbers than female due to the earlier regression of bursa in male birds.

Antemortem findings :

Postmortem findings :

Judgement : The carcass of a bird affected with lymphoid leucosis is condemned. The condemned material may be used for animal food.

Differential diagnosis : Between lymphoid leucosis and Marek's disease is shown in Table 3.

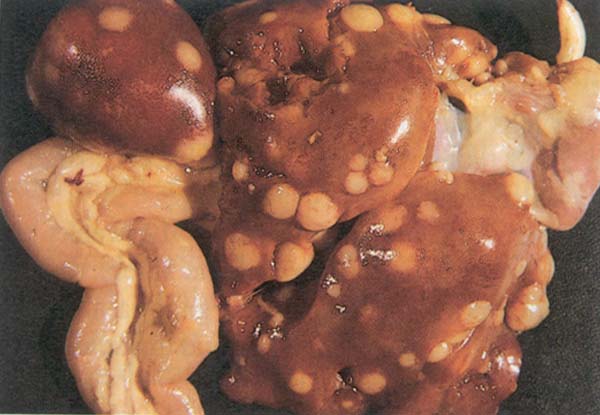

Fig. 198: Avian leucosis complex. Diffuse nodular lesions in the liver, spleen, intestine and heart.

Marek's disease is caused by the herpes virus (DNA).

Transmission : It is spread by airborne infection involving follicle cells called chicken dander. Transmission of the virus is horizontal. At room temperature the virus of Marek's disease remains viable for 16 weeks and in litter for 6 weeks. Birds are most susceptible to the infection during the first few weeks of life. Infected birds will start to shed the virus in the second or third week after infection and will continue to do so throughout their life, although they do develop antibodies against the virus.

Marek's disease is commonly associated with coccidiosis in the field. This is probably due to lack of immunity against coccidiosis in birds affected with Marek's. There are 6 types of Marek's disease.

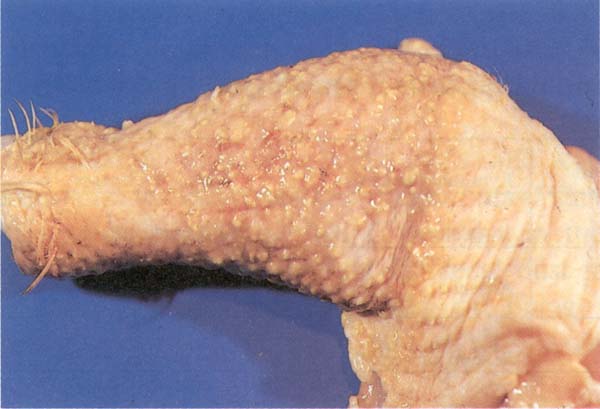

Fig. 199: Avian leucosis complex. Neoplastic lesions of Marek's disease in the leg.

Postmortem findings :

Judgement : Carcass of a chicken affected with Marek's disease is condemned in the extensive cutaneous form and in the visceral form. Localized skin lesions require the condemnation of the affected portions, the rest of the carcass may be approved. The condemned material may be used for animal food.

Differential diagnosis (for skin lesions) : Lymphoid leucosis (see Table 7), erythema, dermatitis, pigmentation and normal large follicles. If the central nervous system is affected the lesions of Marek's disease should be distinguished from those of Newcastle disease and of avian encephalomyelitis. In immunized birds for Marek's disease, the inflammation of the feather follicles (folliculitis) may be caused by the Marek's disease virus. In both cases follicular enlargement is noted; however, the lesion may differ in colour. In immunized birds the lesions of folliculitis are yellowish-white, whereas with the Marek's virus, lesions are blue-grey in colour with a pinkish appearance due to petechial haemorrhage.

| Feature | Lymphoid leucosis | Marek's diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Age of onset | 16 weeks | 4–6 weeks or older |

| Symptoms | Absent | Frequently paralysis or paresis |

| Incidence | Seldom above 5 % | Usually above 5 % |

| Gross Lesions | ||

| Peripheral nerve enlargement | Absent | Usually present |

| Bursa of Fabricius | Nodular tumours | Diffuse enlargement or atrophy |

| Skin, muscle or | Usually absent | May be present |

| proventriculus tumours | ||

| Microscopic Lesions | ||

| Peripheral nerve infiltration | Absent | Present |

| Cuffing in white matter of | Absent | Present |

| cerebellum | ||

| Tumour in the liver | Focal or diffuse | Frequently perivascular |

| Bursa of Fabricius | Intra-follicular tumour | Inter-follicular tumours or atrophy |

| Follicular patterns of lymphoid cells infiltration in the skin | Absent | Present |

| Cytology | Uniform lymphoblasts | Pleomorphic mature and immature cells including lymphoblast, small medium and large lymphocytes and reticulum cells. |

Ornithosis is an acute or chronic disease of turkeys, ducks, chicken, pheasants and pigeons. It is caused by Chlamydia psittaci. In psittacine birds such as parrots, parakeets, cockatoos, macaws etc. and humans, this disease is called psittacosis.

Transmission : Wild carrier birds and cage birds transmit Chlamydia to their nestling which may survive and become carriers. Carrier birds shed Chlamydia in their secretions and excretions. Chlamydia present in faecal dust may be inhaled or ingested. Pigeons are suspected of being disseminators of infection.

Antemortem findings :

In turkeys

In pigeons

Postmortem findings :

In turkeys

In pigeons

Judgement : If the disease is suspected on antemortem, birds are treated as suspects and samples should be shipped to the Laboratory. All reasonable precautions should be taken to avoid risk of human contact. If the disease is suspected on postmortem, delayed slaughter of the birds from the same source should be required. Samples are also forwarded to the diagnostic laboratory. Positive laboratory finding necessitate condemnation of the bird or carcass. If the disease is not confirmed the carcass may be approved if otherwise wholesome.

Differential diagnosis : Mycoplasma gallisepticum infection, pasteurellosis, salmonellosis (pullorum disease; bacillary white diarrhoea(BWD))

Salmonellosis is responsible for significant losses to the poultry industry. Salmonella infections in this Manual include pullorum disease, fowl typhoid, arizona infection and paratyphoid. Pullorum disease occurs in chicken and turkeys and is caused by Salmonella pullorum. The greatest losses are in chicken less than 4 weeks old.

Antemortem findings (in young chicks) :

Postmortem findings :

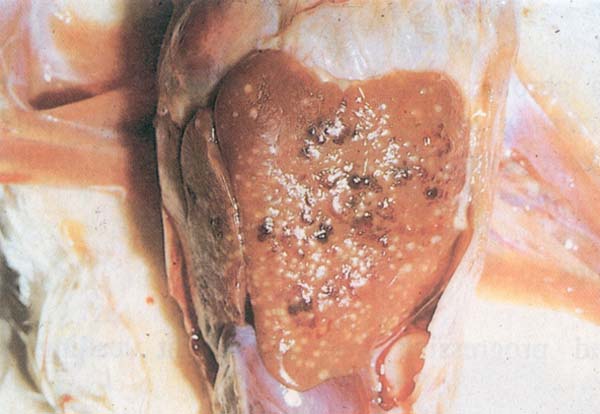

Fig. 200: Pullorum disease. Multiple grey nodules in the heart.

Judgement : Carcass and viscera affected with pullorum disease are condemned.

Differential diagnosis : Liver and heart lesions should be differentiated from infections due to other salmonellae and from campylobacteriosis, colibacillosis and omphalitis. Nervous lesions should be distinguished from nervous signs observed in Newcastle disease. Respiratory tract lesions should be differentiated from aspergillosis and joint lesions with synovitis and bursitis caused by other bacteria or viruses.

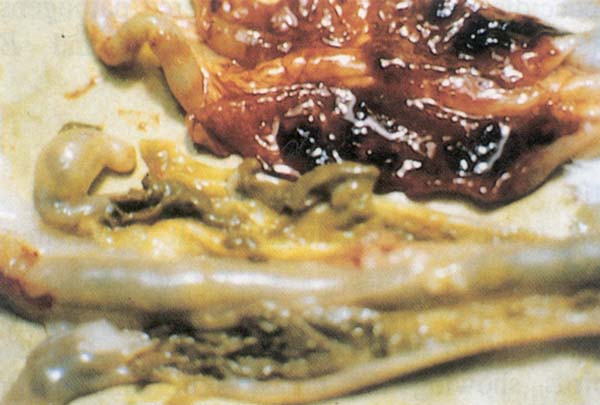

Fowl typhoid is an infectious disease in chicken and turkeys and rarely in other poultry, game birds and wild birds. The causative agent is Salmonella gallinarum. It is seen more often in adult birds. Antemortem signs of fowl typhoid and pullorum disease are similar in birds.

Postmortem findings :

Judgement : Carcass and viscera affected with fowl typhoid are condemned.

Differential diagnosis : see pullorum disease

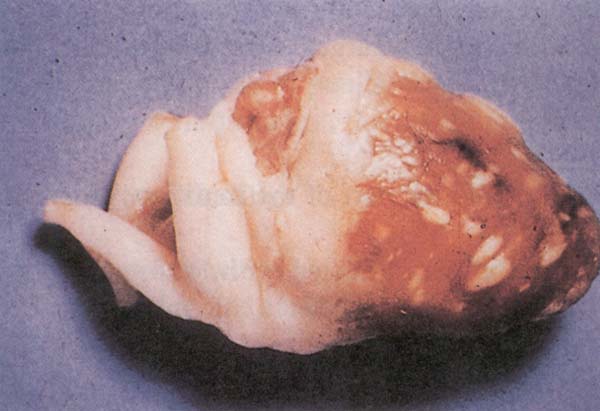

Fig. 201: Fowl typhoid. Enlarged, bronzed to the mahogany colour liver and enlarged, mottled and brittle spleen in a turkey Diseased liver and spleen are shown in contrast to the normal ones at left.

Paratyphoid infection is an acute and chronic infection of poultry and mammals. Ten to twelve species of Salmonella are associated with most outbreaks in poults. The most commonly involved is S. typhimurium in birds less than one month old.

Antemortem findings :

Postmortem findings :

Judgement : Carcass and viscera affected with paratyphoid infection are condemned.

Differential diagnosis : see pullorum disease

Fig. 202: Paratyphoid infection. Button type lesion in the intestine.

Arizoonosis occurs in young turkey poults. It is caused by Arizona hinshawii (Syn. Salmonella arizona). Arizona infection is egg transmitted.

Antemortem findings :

Antemortem findings : Antemortem findings in young birds are similar to those of paratyphoid.

Postmortem findings :

Judgement : Carcass and viscera affected with arizoonosis are condemned.

Differential diagnosis : The causative organism must be isolated and identified for differentiation from salmonellosis.

Fowl cholera is an infectious disease affecting almost all classes of fowl and other poultry. The disease is more prevalent in turkeys than in chicken. It occurs more frequently in stressed birds associated with parasitism, malnutrition, poor sanitation and other conditions. Fowl cholera is caused by Pasteurella multocida. This organism is easily destroyed by sunlight, heat, drying and most of the disinfectants. However, it will survive several days of storage or transportation in a humid environment. It persists for months in decaying carcasses and in moist soil. The agent is frequently carried in the oral cavity of wild and domestic animals.

Transmission : If birds are bitten by infected animals such as rodents and carnivores, the disease could be disseminated in the flock. Contaminated feed, water, soil and equipment are also considered as potential factors in the spreading of the disease.

Antemortem findings :

Acute septicemic form

Chronic fowl cholera

Postmortem findings : In the very acute stages, lesions may be lacking.

In chronic cases

Judgement : Localized lesions of pasteurellosis such as infection of wattles, joints or tendon sheaths require the condemnation of the affected parts; the rest of the carcass is approved. Septicemic carcasses should be condemned.

Differential diagnosis : Acute colibacillosis and erysipelas in turkeys, salmonellosis, tuberculosis, listeriosis. Pasteurellosis is differentiated from septicemic and viremic diseases by culture of P. multocida. Closely related bacteria such as S. gallinarum, P. haemolytica and others may cause a cholera like disease or they may complicate other diseases.

Public health significance : Fowl cholera, although known for 200 years is still a poorly controlled disease in birds. Humans may become infected with this disease, and then they may also infect poultry with exudates from the nose and mouth.

Fig. 203: Fowl cholera. Cheesy exudate in the Infraorbital Sinus.

Fig. 204: Fowl cholera. Small areas of necrosis in the liver (corn meal liver)

Tuberculosis is a chronic granulomatous disease of poultry caused by Mycobacterium avium. It is usually found in older chicken which are kept beyond the laying season. Other poultry are also affected.

Antemortem findings :

Postmortem findings :

Judgement : A carcass affected with tuberculosis is condemned.

Differential diagnosis (on postmortem) : Aspergillosis, typhoid and paratyphoid, salmonellosis, fowl cholera, campylobacter, colibacillosis, chlamydiosis, histomoniasis and neoplasm. In neoplasm, the cut surface of the lesion is uniform and without necrosis.

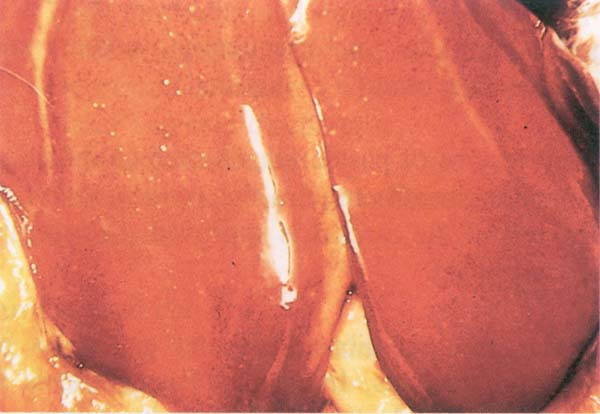

Fig. 205: Tuberculosis. Greyish white nodules in the liver

The term “Air sac disease” usually refers to a respiratory syndrome characterized by airsacculitis, perihepatitis and pericarditis in broiler chickens between 4 – 8 weeks of age. Pneumonia is also frequently present. Primary factors associated with the etiology of air sac disease are poor air quality and dust, associated with either viral or mycoplasmal agents. E. coli is usually a secondary invader.

Chronic respiratory disease (CRD) refers to respiratory infection of the upper respiratory tract of chicken caused by Mycoplasma gallisepticum. This agent affects turkeys more severely and causes infectious sinusitis.

Postmortem findings : Postmortem examination of affected chicken reveals inflammation of trachea and frothy exudate in the air sacs. With presence of secondary invaders, inflamed airsacs have a opaque appearance in the early stages of infection (Fig. 206). In the later stages airsacs are thickened and caseous yellow exudate is usually present. Yellow fibrinous deposits on the pericardium (pericarditis) and liver (perihepatitis, Fig. 207) are also observed.

Fig. 206: Chronic Respiratory Disease. Cloudy appearance of the abdominal airsacs in this 7 week old chicken.

Fig. 207: Pericarditis and perihepatitis in an eight week old chicken. E. coli was isolated from both lesions.

Judgement : In poultry inspection, it is of great importance to differentiate between the inflammation of the air sacs (airsacculitis) and peritonitis, as well as pathologic changes in the air sacs and bones. The communication of some air sacs and bones has to be observed during the judgement of carcasses with airsacculitis and bone diseases. Birds affected with airsacculitis are treated as suspects on antemortem examination. On postmortem examination affected parts with localized lesions are condemned and the rest of the carcass is approved if in good condition and no spread of infection into bones is noted. The rational for approving a carcass in good condition with localized lesions of airsacculitis may be supported with frequent negative findings of microorganisms in these lesions. Since an accumulation of the fluid in the airsacs and associated opacity may be early signs of infection, the other birds in the flock must also be examined. Sufficient evidence must be obtained in that these lesions would remain localized. Otherwise the carcass must be condemned. Generalized and extensive lesions of airsacculitis require total condemnation of the carcass. If pericarditis or perihepatitis are the only lesions present on postmortem the carcass may be approved if otherwise wholesome.

Histomoniasis is a protozoal disease of turkeys, chicken and game birds. It often occurs in turkeys run with or after chicken. It is caused by Histomonas meleagridis which is transmitted in the ova of caecal worms (Heterakis gallinarum) and by earth worms. Well developed hepatic and caecal lesions are pathognomonic for histomoniasis.

Antemortem findings :

Postmortem findings :

On microscopy, histomonas are found in the caecal wall or in the liver lesion.

Fig. 208: Histomoniasis. Circular yellow necrotic tissue surrounded with white rings of a turkey liver.

Judgement : The bird is approved if in good flesh. The liver and intestine are condemned. The carcass is condemned if emaciated or associated with septicemia.

Differential diagnosis : Salmonellosis, coccidiosis, aspergillosis and trichomoniasis.

Coccidiosis is a major disease problem in commercial poultry and the most common cause of enteritis. It is caused by various species of the protozoan genus Eimeria. At least nine species have been described in chicken. The most important of these are E. acervulina, E. brunetti, E. maxima, E. necatrix and E. tenella.

The identification of different species of coccidia is based on the distribution of the lesion in the intestine, gross and microscopic appearance, and the size and shape of oocysts. Coccidia are species specific which means that coccidia in chicken will not be found in turkeys and vice versa.

Whether the coccidia actually cause illness or death of the bird depends on the species, dose, location of parasitic reproduction and immune status of the bird. Birds affected with Marek's disease and IBD are more susceptible to coccidiosis.

If parasitic reproduction occurs in the epithelium of the intestine, disease follows and if it occurs subendothelially, the birds usually bleed to death in acute cases.

With ingested oocysts moving to the intestinal lining, the life cycle of coccidia begins. Intestinal cells are damaged and in 4 – 8 days, depending on the species, oocysts are shed in the faeces.

Within 12 – 30 hours in a moist environment and in a temperature of 20 – 30°C, the oocysts sporulate and become infective. Birds raised on the range will have more outbreaks of this condition in the spring and summer compared to birds raised in total confinement of barnyards. In the latter, outbreaks can occur at any time.

Coccidiosis causes severe losses in intensive broiler production and in layers, it causes a drop in egg production. This is in spite of great discoveries of many different coccidiostats. Even when the disease is controlled, medication expenses run very high.

Antemortem findings :

Findings in poults include:

Judgement : Birds affected with severe coccidiosis associated with emaciation or anaemia are condemned. Otherwise, the carcass is approved, after the condemnation of affected tissue.

Differential diagnosis (on postmortem) : Necrotic enteritis, ulcerative enteritis, salmonellosis, ascariasis, capillariasis, haemorrhagic disease, leucosis, blackhead, bluecomb and haemorrhagic enteritis in turkeys

I. Chicken coccidiosis

(A) E. acervulina

E. acervulina is found in the duodenum and upper jejunum. It is frequent in growing birds and broilers and causes duodenal coccidiosis.

Postmortem findings:

(B) E. brunetti

E. brunetti is found in the lower small intestine, rectum and proximal part of ceca.

Postmortem findings:

(C) E. maxima

E. maxima is found in the middle part of the small intestine and less frequently, throughout the intestine

Postmortem findings:

(D) E. tenella

E. tenella is found in the ceca. It causes caecal coccidiosis.

Postmortem findings:

(E) E. necatrix

E. necatrix is found in the middle part of the intestine near the yolk sac diverticulum. In severe cases, this coccidium is observed throughout the intestine and ceca. It causes acute mortality and weight loss in laying birds.

Postmortem findings: Intestinal distention, mucoid blood filled exudate and white spots noted on the serosa (Fig. 210)

Fig. 209: Coccidiosis. Haemorrhage in the ceca characteristic of E. tenella infection.

Fig. 210: Intestinal distention, mucoid blood filled exudate and white spots noted on the serosa with E. necatrix infection.

II. Coccidiosis in turkeys

Three species of coccidia in turkeys are considered pathogens. These include E. meleagrimitis, E. adenoeides and E. gallopavonis.

(A) E. meleagrimitis

E. meleagrimitis is found in small intestine. It is the most pathogenic for turkeys.

Antemortem and postmortem findings:

(B) E. adenoeides

E. adenoeides is found in the lower small intestine, ceca and large intestine.

Postmortem findings:

(C) E. gallopavonis

E. gallopavonis is found in the lower one-third of small intestine, large intestine and ceca.

Postmortem findings: