1 Natal Sharks Board, P. Bag 2 Umhlanga Rocks 4320, South Africa

2 Northern Fisheries Centre, Queensland Department Of Primary Industries PO Box 5396, Cairns, Australia

1. INTRODUCTION

Shark control “fisheries” are either fully or heavily subsidised, their objective being to minimize shark numbers in the vicinity of bathing beaches to reduce the risk of shark attack. Economically, the justification is enhancement of coastal tourism. Passive barrier nets - or fences which exclude but do not capture sharks, provide another method of protection. A barrier was built off a Durban beach in 1907 and more were built off several other KwaZulu-Natal beaches in the late 1950s (Davies 1964). One was constructed at Coogee, New South Wales, in 1929 (Anon 1935). These barriers proved impractical to maintain in heavy surf and no longer exist (Davies 1964, Coppleson and Goadby 1988). A fence was used to protect the private bathing beach at the Florida home of a former president of the USA (Reader's Digest 1986). Enclosures have existed at some Croatian beaches since the 1920s and, although their status today is unknown, some were still in existence as recently as 1995 (I.K. Fergusson, The Shark Trust, pers. comm.). Barrier nets are in still in use in some sheltered environments such as at Sydney Harbour, Queensland's Gold Coast marinas and Hong Kong. Such barrier nets are not considered further here.

Three major shark control (or “meshing”) programmes - which between them catch about 2500 sharks annually - are known to exist. These are in New South Wales (NSW) and Queensland, Australia, and KwaZulu - Natal (KZN), South Africa. In addition, large-mesh shark nets provide bather protection off the beaches of Dunedin, New Zealand. Shark control has been conducted in the past by the state government of Hawaii but this has been discontinued. Shark nets of an unknown type were in use at the main bathing beach in Qingdao (Shantung Province, China) in 1982 (R.B. Clark, University of Newcastle, pers. comm.). Whether such nets still exist there or elsewhere in China is unknown. The focus of this report is on the management of the three major programmes.

2. KWAZULU-NATAL SHARK CONTROL PROGRAMME (NATAL SHARKS BOARD)

2.1 Species targeted by programme

The objective of these programmes is to catch those shark species which are regarded as potentially dangerous. One or more individuals of each of 14 species of shark are captured each year (Table 1). Of these, three species are believed to have been responsible for most attacks, the bull (Zambezi) shark (Carcharhinus leucas), the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) and the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier). Associated bycatch species, which may be discarded, are listed in Table 2 together with mean annual catches and the percentage released.

2.2 Distribution of programme

The geographical limits of the programme are Richards Bay (28°48'S, 32°06'E) in the north and Mzamba (31°05'S, 30°11'E) in the south, the latter falling just outside the province of KwaZulu-Natal. All the shark species caught in the programme have a considerably wider distribution in the western Indian Ocean (Compagno 1984a, b) than the netted region (Dudley and Cliff 1993a).

| Species | Common name | Species | Common name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carcharodon carcharias | Great white | Isurus oxyrinchus | Shortfin mako |

| Galeocerdo cuvier | Tiger | Carcharias taurus | Spotted ragged-tooth |

| Carcharhinus leucas | Bull (Zambezi) | Carcharhinus amboinensis | Java |

| Carcharhinus obscurus | Dusky | Carcharhinus plumbeus | Sandbar |

| Carcharhinus brachyurus | Copper | Sphyrna zygaena | Smooth hammerhead |

| Carcharhinus brevipinna | Spinner | Sphyrna lewini | Scalloped hammerhead |

| Carcharhinus limbatus | Blacktip | Sphyrna mokarran | Great hammerhead |

Several other shark species are captured at a rate of less than one per year.

2.3 Development and current status of the programme

2.3.1 Methods of catching

Sharks nets were installed in response to the negative impact of shark attacks on local tourism. Encouraged by the success of the NSW meshing programme (Wallett 1983), the City Engineer of Durban installed 12 gill nets (shark nets) in 1952 (Davies 1964, Hands 1970). The first recorded meshing of beaches other than those under the control of the Durban City Council was the introduction of two nets at Amanzimtoti in August 1962 (Wallett 1983). In November 1997 there was a total of 41 km of netting in the water, providing protection at 64 bathing areas.

Most of the nets are 213.5m long by 6.3m deep, made of black mesh material of 51cm and are set parallel to the coast in 10–14m of water, 300–500m from shore. The hang-in coefficient is 40%. The specifications have been modified slightly since the 1960s, one of the major changes being the joining of pairs of 106.75m nets in the early 1980s to form the current “double” nets. The nets at Durban, Anstey's Beach and Brighton Beach differ from those used elsewhere in that they are yellow and, although originally 137m long and 7.6m deep, since 1963 have measured 304.8m in length (Hands 1970).

The nets in an installation are set in two rows parallel with each other and to the beach. The rows are approximately 20m apart and staggered, with an overlap of some 20m. They are usually laid at, or near, the surface but tend to sink as they become fouled. (Wallett 1983). Each net is replaced with a clean one approximately every 10 days. The nets are serviced (“meshed”) at first light from a fleet of 20 “skiboats” - open-deck boats with twin, tilting outboard motors - and a crew of five. Most of the boats are 5.5m monohulls which are launched through the surf but there are also five 6.5m boats, including both catamarans and monohulls, of which four operate from harbours.

2.3.2 Vessels used and evolution of fishing effort

The Durban nets were serviced initially by private contractors and there are no published details about the vessels used. In 1960 the City Engineer's Department of the Durban City Council took over the operation and a 13.4m boat, with an inboard motor and a crew of eight, was purpose-built. A second boat, measuring 15.2m, was introduced several years later (Davies 1964, Hands 1970). Such boats depended on harbours. When shark nets were installed elsewhere - off beaches with no harbour facilities - the smaller skiboats, suitable for surf launches, were introduced.

| Species | Common name | Caught (nb) | Released (%) | Species | Common name | Caught (nb) | Released (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birds | Gvmnura natalensis | Backwater | 49.6 | 78 | |||

| butterflyray | |||||||

| Sula capensis | Cape gannet | 1.3 | 0 | Himantura gerrardi | Sharpnose | 1.4 | 93 |

| stingray | |||||||

| Phalacrocorax sp. | Cormorant | 0.1 | 0 | Himantura uarnak | Honeycomb | 1.9 | 84 |

| stingray | |||||||

| Spheniscus demersus | Jackass | 0.1 | 0 | Torpedo sinuspercici | Marbled | 0.4 | 25 |

| penguin | electric ray | ||||||

| Torpediniformes | Electric ray | 0.6 | 100 | ||||

| Rhina ancylostoma | Bowmouth | 0.1 | 100 | ||||

| Turtles | guitarfish | ||||||

| Eretmochelys imbricata | Hawksbill | 1.8 | 28 | Rhynchobatus | Giant | 122.0 | 75 |

| djiddensis | guitarfish | ||||||

| Lepidochelys Olive ridley | Olive ridley | 1.1 | 27 | Pristis microdon | Largetooth | 0.2 | 100 |

| sawfish | |||||||

| Caretta caretta | Loggerhead | 42.6 | 35 | Pristis pectinata/zijsron | Smalltooth/ | 0.9 | 67 |

| green sawfish | |||||||

| Chelonia mydas | Green | 14.0 | 34 | Pristis spp. | Sawfish | 1.0 | 70 |

| Cheloniidae | Unidentified | 1.1 | 73 | ||||

| turtle | Teleosts | ||||||

| Dermochelys coriacea | Leatherback | 6.8 | 35 | Sphyraena spp. | Barracuda | 0.3 | |

| Trachinotus blochi | Snubnose | 1.2 | |||||

| pompano | |||||||

| Cetaceans | Lichia amia | Garrick | 11.5 | ||||

| Sousa plumbea | Indo-Pacific | 6.1 | 2 | Scomberoides spp. | Queenfish | 1.8 | |

| humpbacked | |||||||

| dolphin | |||||||

| Delphinus delphis | Common | 36.3 | 4 | Caranx ignobilis | Giant kingfish | 0.2 | |

| dolphin | |||||||

| Tursiops truncatus | Bottlenose | 34.9 | 1 | Carangidae | Unidentified | 0.2 | |

| dolphin | kingfish | ||||||

| Stenella coeruloealba | Striped | 0.3 | 33 | Thunnus albacares | Yellowfin | 4.6 | |

| dolphin | tuna | ||||||

| Stenella longirostris | Spinner | 0.1 | 0 | Euthynnus affinis | Eastern little | 2.0 | |

| dolphin | tuna | ||||||

| Lagenodelphis hosei | Fraser's | 0.1 | 0 | Katsuwonus pelamis | Skipjack tuna | 4.3 | |

| dolphin | |||||||

| Pseudorca crassidens | False killer | 0.1 | 0 | Scomberomorus | King | 0.6 | |

| Whale | commerson | Mackerel | |||||

| Delphinidae | Unidentified | 0.9 | 0 | Scomberomorus | Queen | 0.5 | |

| dolphin | plurilineatus | mackerel | |||||

| Balaenoptera | Minke whale | 0.4 | 25 | Scombridae | Unidentified | 1.2 | |

| acutorostrata | tuna, bonito | ||||||

| Rachycentron canadum | Prodigal son | 0.9 | |||||

| Sharks | Argyrosomus japonicus | Kob | 3.2 | ||||

| Rhizoprionodon acutus | Milk | 4.6 | 6 | Atractoscion aequidens | Geelbek | 1.5 | |

| Mustelus mosis | Hardnosed | 0.2 | 50 | Makaira indica | Black marlin | 0.9 | |

| smooth-hound | |||||||

| Halaelurus lineatus | Banded cat | 0.1 | 0 | Istiophorus platypterus | Sailfish | 0.1 | |

| Rhincodon typus | Whale | 0.7 | 57 | Elops machnata | Ladyfish | 1.0 | |

| (springer) | |||||||

| Squatina africana | African angel | 32.9 | 45 | Epinephelus lanceolatus | Brindlebass | 0.4 | |

| Epinephelus tukula | Potato bass | 0.1 | |||||

| Sparodon durbanensis | White | 0.3 | |||||

| Batoids | musselcracker | ||||||

| Aetobatus narinari | Spotted | 14.0 | 80 | Cymatoceps nasutus | Black | 0.7 | |

| eagleray | musselcracker | ||||||

| Myliobatis aquila | Eagleray | 3.7 | 54 | Oplegnathus spp. | Knifejaw | 0.2 | |

| Pteromylaeus bovinus | Bullray | 37.8 | 61 | Tripterodon orbis | Spadefish | 0.1 | |

| Rhinoptera javanica | Flapnose ray | 41.1 | 58 | Pomadasys kaakan | Javelin | 0.3 | |

| grunter | |||||||

| Manta birostris | Manta | 52.5 | 66 | Unidentified | 1.0 | ||

| fish | |||||||

| Mobula spp. | Devilray | 14.2 | 60 | ||||

| Dasyatidae | Unidentified | 6.5 | 74 | ||||

| stingray | Crustaceans | ||||||

| Dasyatis chrysonota | Blue stingray | 0.8 | 88 | Panulirus homarus | Crayfish | 0.1 |

In 1974 the Natal Sharks Board (NSB) - which since its inception in 1964 had had a coordinating and supervisory role only - began to take over the servicing and maintenance of nets from independent contractors and municipal employees. By 1982 the NSB was solely responsible for all shark nets on the KZN coast (Davis et al. 1989). Nets have, since inception, remained in the water throughout the year, except that from 1975 it became policy to lift some nets temporarily during the annual “sardine run”, the winter influx of pilchard into southern KZN waters (Cliff and Dudley 1992 a, b). Average meshing frequency was no more than weekly until the early 1970s, but increased to 10 meshings per month by 1974. The frequency has been between 15 and 20 times per month since the late 1970s (Cliff et al. 1988).

Total effort, expressed as kilometres of netting, increased from 1.6km in 1952 to a peak of just over 44km in the late 1980s and early 1990s and subsequently decreased to 41km at the end of 1997.

2.4 Markets

The NSB sells certain shark products to defray expenses. Income from such sales is small relative to total expenditures. Products sold from the Board's curio shop include shark teeth - sold either loose or with a jump ring for attachment to a jewellery chain - and entire jaw preparations. In addition, dried fins are stockpiled and sold, usually annually. Initially sales of fins were to local exporters by a tender process but the NSB is now investigating direct export. Fins and teeth from great white sharks Carcharodon carcharias are not sold because the species is locally protected. The meat from netted sharks is generally not sufficiently fresh for human consumption. Experimental inclusion of the meat in animal feed has been unsuccessful.

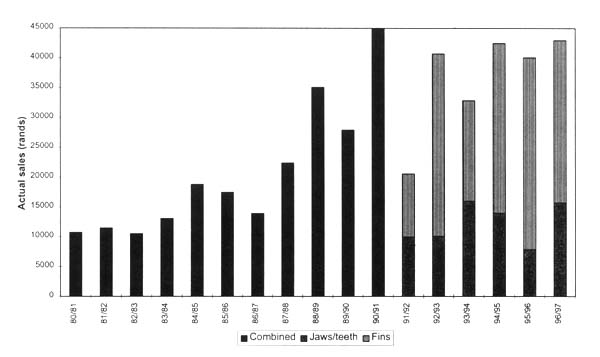

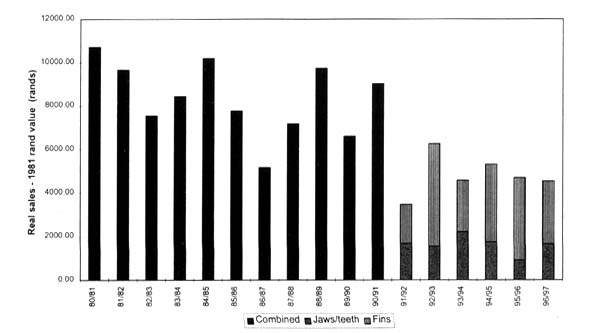

Although there has been an increase in current values with time (Figure 1), these have not kept pace with inflation (Figure 2). The drop in real value in the 1990s is partly due to a ban since 1991 on the sales of white shark jaws and teeth. Fluctuations in revenue are linked to annual catch.

2.5 Economics of the programme

The programme, by nature, is not directly profitable and is almost fully subsidised. In the 1996/97 financial year income was derived from the following sources (approximate figures): subsidy from provincial government of KwaZulu-Natal - R12.4m ($2.8 m), meshing fees paid by coastal local authorities (municipalities etc.) which have protected beaches - R3 m ($0.7m), sundry income, including entrance fees to public shows and sales of shark products - R347 200 ($0.1 m). The economic justification for the existence of the programme is that it is integral to the tourism infrastructure of KZN. The annual contribution of tourism to the economy of KZN is at least R6bn ($1.3bn), or 10% of the Gross Geographic Product (J. Seymour, KwaZulu-Natal Tourist Authority, pers. comm.) Not all of this is attributable to coastal tourism, but most of the tourism infrastructure in the province is associated with coastal resorts (Dudley 1998).

2.6 The programme's workforce

Initially the NSB consisted of a board only and had no permanent staff. In 1966 B. Davis, subsequently the NSB's first director, was employed to act as a liaison officer between the NSB and those local authorities which had netted beaches. In 1968 the NSB began to employ its own staff and by 1997 a workforce of some 220 personnel was employed on a full time basis. Of these, 156 are operations staff directly responsible for meshing activities and the remaining 64 provide administrative, financial, logistical, research and public relations support. The research staff includes four scientists.

Figure 1

Sales of products from sharks netted in the KZN programme (current terms) (1996/97 approximate exchange rate R4.50=$1.00)

2.7 Management objectives

2.7.1 The programme within the context of national fisheries policies

A new Marine Living Resources Bill is set to form the basis for a new Sea Fishery Act. Nine objectives and principles underpin the Bill. Probably the most pertinent of these, with regard to shark control, are the following:

the need to conserve marine living resources for both present and future generations

the need to apply precautionary approaches in respect of the management and development of marine living resources

the need to utilise marine living resources to achieve economic growth, human resource development, employment creation and a sound ecological balance consistent with the development objectives of the national government

the need to protect the ecosystem as a whole, including species which are not targeted for exploitation

the need to preserve marine biodiversity.

A shark control programme is a unique application of the concept of exploiting marine resources, perhaps equating most closely to angling in that in both cases the basis for exploitation is recreation. The analogy breaks down however, in that shark control is a means to an end rather than an end in itself. The ecological considerations which must be taken into account in the management of shark control are addressed in all of the objectives and principles listed above. It is, however, the achievement of economic growth, human resource development and employment creation by providing a component of the tourism infrastructure of KZN that provides the economic justification for shark control in terms of the Bill.

Figure 2

Sales of products from sharks netted in the KZN programme (real terms)

Pending the promulgation of the new Act, living marine resources in South Africa are protected by the Sea Fishery Act of 1988. In terms of the Act the NSB is required to possess permits (a) to use and be in possession of gill nets, (b) catch and be in possession of great white sharks; and (c) catch (incidentally) and be in possession of dolphins. In addition, the NSB is required in terms of the KwaZulu-Natal Nature Conservation Ordinance of 1974 to have a permit to capture, by means of shark nets only, and be in possession of, any marine turtle.

A draft Marine Fisheries Policy for South Africa, dated May 1997, proposes that central government, in serving the principle of sustainable utilisation, should consider devolving research responsibility to a number of institutions, including the NSB.

2.7.2 Objectives for the management of the shark control programme

The major objective of a shark control programme - minimising the risk of shark attackdiffers from the objectives of “conventional” fisheries. Another unusual feature of the programme is that the managers are also the prosecutors of the fishery and thus it is in management's direct interest to achieve a second objective - minimising operating costs. A third and more conventional management objective is to minimise environmental impact. A fourth objective is to use the opportunity afforded by the capture of sharks and other animals to conduct biological research.

The primary objective was set because of the negative economic impact of shark attack (Davies 1961). As early as 1907 a shark barrier was built on Durban's beachfront “to ensure that there was safe bathing and as a protection from shark attack” (Davies 1964). At the time of the introduction of shark nets in 1952 there seems to have been no consideration of the ecological consequences of shark control. At its inception in 1964 the NSB was charged “with the duty of approving, controlling and initiating measures for safeguarding bathers against shark attack” (Natal Ordinance No. 10 of 1964). There has subsequently been a gradual change in philosophy such that mortalities of marine organisms - including sharks - are minimised (Cliff and Dudley 1992a), yet without compromising bather safety unduly. Symbolic of this was a change in name from the Natal Anti-shark Measures Board to the Natal Sharks Board.

There has been a degree of compromise in combining objectives one, three and four, notably the tagging (where possible) and releasing of all sharks found alive in the nets. Released sharks constitute about 15% of the total shark catch. The NSB argues, however, that the nets achieve their protective function primarily by maintaining local shark numbers at a considerably lower level than in the pristine state and that the occasional release of a potentially dangerous shark will have a negligible effect on their numbers. Also, the release of sharks takes place at first light when there are few bathers in the water and it is believed that the released animals tend to move into deeper water (Cliff and Dudley 1992a).

2.7.3 Discussion

The management objectives at the “fishery level” are clear but they are by no means prescriptive in terms of setting management policy, i.e. the manner whereby they should be achieved. Stakeholders include the provincial government (the major funder), coastal municipalities and other local authorities with protected beaches, the tourist industry, recreational users of the sea, environmentalists, conservationists and members of any fishery which might be affected directly, or indirectly, by a reduction in numbers of large sharks. The majority of stakeholders appear satisfied with the objective setting process in that they all influence, directly or indirectly, the process. Indeed, shark control would not exist if it were not for public demand. Dissatisfaction at perceived or real environmental impact has been expressed, however, by environmentalists, conservationists and recreational anglers. The response of the NSB has been to research these impacts to determine their severity and to seek methods of reducing them. Dissatisfaction has also been expressed by certain local authorities whose shark nets have been removed on economic grounds because of low bather numbers.

2.8 Management policies and the policy setting process

2.8.1 Identification and evaluation of policies

Policy options for the provision of safe bathing may be divided broadly into either providing a physical barrier between sharks and bathers or reducing locally the numbers of potentially dangerous sharks, thereby reducing the likelihood of an encounter between sharks and bathers. The NSB has adopted the latter. Physical barriers (“shark fences”) were used in the early part of the century (Durban) as well as in the late 1950s and early 1960s (various municipalities). Long term maintenance of these unsightly structures in heavy surf conditions proved expensive and impractical.

By the time the NSB came into existence in 1964 there were already several net installations in existence in addition to that at Durban which had been established in 1952. These installations were maintained by contracted commercial fishermen or by municipal employees. Initially the role of the NSB was supervisory but in 1974 the decision was taken to gradually assume direct responsibility for the maintenance of all net installations. This process was completed in 1982. Reasons for the decision included (1) ensuring a consistently high level of service by means of using trained staff, (2) achieving a reduction in costs replacing with a single NSB meshing team two or more contractors/municipal teams which were servicing adjacent beaches and (3) improved collection of biological and environmental data, including a high level of accuracy in the identification of species in the field, and the retrieval of dead sharks and other animals for dissection.

The nets are maintained in fixed localities throughout the year. Although the use of nets was inspired by a similar practice in Sydney, NSW, the two programmes differ markedly in the quantity of gear deployed per beach and the length of time the gear is in the water. In NSW a “roster” system” is used, with nets being moved from beach to beach. There appears to be no documented explanation for the Durban City Council's decision to deploy nets at each beach on a permanent basis. Davies (1961) suggested that the use in NSW of supplementary beach patrols when bathing densities were high may have been a factor, and that the higher turbidity of KZN waters would preclude a similar practise, but Dudley (1997) argued that as this is dependent upon human vigilance it is unlikely to explain why the NSW meshing programme has succeeded over a 50 year period despite a relatively low level of fishing effort.

Decisions on the number of nets to deploy per beach were made on the intuitive basis of “beach coverage”. Fewer nets were deployed off a beach situated in a “natural curve of the coastline” (Wallett 1973, p. 17), because of the physical restriction on a shark's approach to that beach from the sides, than at a beach on a straight Section of coastline. Also, if shallow water inshore dictated that the nets be set further offshore than normal, more nets were set. Wallett's stated relationship between coastline topography and number of nets is difficult to test objectively because most of KZN's netted beaches are defined by Cooper (1991 a, b, 1994) as embayments, albeit poorly developed.

The increase in the frequency with which nets are serviced - from approximately weekly until the late 1970s to the present frequency of about 20 times per month - has led to a substantial decrease in undetected captures which used to result from sharks decomposing and falling out of the nets. Similarly, the survival rate of captured animals has increased, though operating costs also increased.

In the 1960s and 1970s most requests for new net installations were granted, the exception being those for areas regarded as particularly environmentally sensitive. More recently, with the increase in environmental awareness, such requests are treated more conservatively and new installations are seldom established. Coupled with this are the recently introduced policies of effort reduction and catch and bycatch reduction. Effort reduction includes the complete removal of net installations at underutilised beaches and, where possible, a reduction in the size of other installations. In a comparison of the shark control programmes of KZN, Queensland and NSW, Dudley (1997) concluded that there is a case for reducing the number of nets used per beach in KZN. Catch and bycatch reduction could be achieved by effort reduction but also by modifying the existing nets (e.g. increased mesh size, use of passive or active dolphin repellents) and/or through the use of alternative gear such as the baited drumlines used in Queensland. These options have been, or are being, researched.

2.8.2 Policies adopted

A single type of gear - a large-mesh anchored gill net - is used.

Each beach is permanently netted except during the “sardine run” when some net installations are temporarily removed.

The nets are serviced at first light about 20 times per month. All live animals are released. Sharks and some rays are tagged. Dead animals are retrieved and used for research.

Fins, teeth and jaws from dead sharks are sold to offset expenses.

Requests for new net installations are treated conservatively.

The NSB is engaged in ongoing research into effort and by catch reduction.

The policies have been effective in achieving a reduction in risk of shark attack. At Durban the rate of attack resulting in a fatality or a serious injury dropped from 0.58/y- to zero with the introduction of nets, and at KZN's other meshed beaches the decline was from 1.08 to 0.10 (91% reduction). Effort reduction, i.e. a reduction in the number of nets per installation, has not yet reached the point where it has resulted in cost reduction. An exception was the permanent removal of two installations which resulted in one boat unit being taken off the water. Mortalities have been reduced through the policies of releasing all live animals and lifting nets during the sardine run, but could be reduced further with modified and/or alternative gear. The general research objective is being achieved, NSB scientists having published almost 50 peer-reviewed articles in the last decade.

2.9 Gears used

The nets are described in Section 2.2. Their original design was adaptated from those which had been found to be effective in the NSW programme. The mesh size of 50.8cm bar exhibits a peak relative selectivity to sharks (all netted species combined, excluding hammerheads) of about 215cm precaudal length (Dudley 1995). The relative selectivity to sharks of 160cm precaudal length (the size taken as being that of the smallest potentially dangerous shark) is 81%, whereas the selectivity of a 70cm mesh net to the same animal is only 25% (Dudley 1995). Thus, although the larger mesh would take a smaller bycatch, the potential increase in risk to bathers is considered unacceptable.

Drumlines, each consisting of a baited hook suspended from an anchored drum, are an alternative method of capture to nets. The advantage of drumlines is that they take a far smaller nonshark bycatch than nets and are more selective in terms of shark species caught. They have been used since inception in the Queensland programme but are not used by the NSB. Criticisms of drumlines include that they (i) may attract sharks; (ii) are only functional while baits are on the hooks and the baits are subject to scavenging; and (iii), do not offer the partial physical barrier effect of nets. Despite these concerns, drumlines have proven successful in the Queensland programme and experiments with drumlines are under way in KZN.

2.10 Biological regulations

The KZN programme is governed by the national and provincial regulations described in Section 2.7.1. In addition, self-imposed regulations include the release of all live animals, the tagging of live sharks and some batoids and the retention of dead animals for biological research and sale of certain parts.

2.11 Expansion/reduction of the programme

The NSB is reluctant to expand the programme within KZN waters. Catches appear to be sustainable - with the possible exception of the humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) - but obviously unlimited expansion of the programme would change this. No new installation would be established without first inviting public comment. It is likely that any new installations would have to be selffunded.

The NSB monitors bather numbers at netted beaches and makes recommendations to the KZN government with regard to the removal of nets from under-utilised beaches. All but one of the beaches protected by the NSB fall within KZN, the exception being a beach which lies two kilometres beyond the border with the Eastern Cape Province. The NSB does accept contract work in other parts of the world, but prefers to install passive barrier nets where possible rather than shark-catching gear.

2.12 Discussion

The policy setting progress has been successful in terms of achieving the primary objective of the programme, namely a major reduction in risk of shark attack. Probably the major weakness is that there has historically been little opportunity for the public to comment on the process. Also, there is no regular internal policy review process, the development of policy being somewhat ad hoc. Both these weaknesses require consideration.

3. THE MANAGEMENT PROCESS

3.1 Provision of resource management advice

Unlike commercial fisheries, in which research and management are usually conducted by one or more government agencies and the fishing activities themselves by the private sector, in the case of the KZN shark control programme the NSB is responsible for all three functions. The research department of the NSB monitors trends in catch data. Its mandate is to recommend research projects to improve understanding of the biology of the netted species and the ecological effects of the programme. It also recommends and supervises projects to reduct catch (including bycatch) and effort. The NSB has a board, appointed by the provincial government, which meets monthly, inter alia to approve policy, and an executive management which ensures the implementation of policy. Actual implementation is done by the operations staff. Because the entire process is internal it has advantages in data capture, communication between researchers, management and operations staff (meshing teams) etc. A potential disadvantage for the process is lack of transparency (see Section 3.4).

3.2 Fishery statistics

The nets are meshed at first light about 20 days per month. Upon completion, each meshing team reports by radio the day's catch and bycatch, by species, to the NSB research department. Other data reported include physical conditions at the nets and sightings of cetaceans. Once the dead sharks have been dissected in the NSB laboratory, biological information is recorded.

There were considerable problems with the accuracy of the data - particularly with regard to species identification but also with regard to total catch figures - until the late 1970s. Since then the quality of data is considered to be good and the officer in charge of each meshing team takes periodic retraining in species identification. The identification of all animals brought to the NSB laboratory is checked by research staff and is seldom found to be incorrect.

Data are stored on computer using Borland's dBase III+TM. The intention is to convert to Microsoft AccessTM during 1998. Monthly catch reports are supplied to local authorities which have netted beaches and annual catch reports are submitted to the Chief Directorate; Sea Fisheries. Most requests for data come from researchers working on the KZN coast who require physical environmental data. These requests are generally granted and a preparation fee is levied at the discretion of the NSB chief executive.

3.3 Stock assessment

The NSB programme is characterised by having size-selective fishing gear (gill nets) deployed in fixed localities. Thus a very small part of the geographical range of each shark species is sampled, and always in the same places. Also, there are no other fishery-independent data for most of the shark species caught. This renders the data collected by the programme of some value for stock assessment purposes. Total shark catch is shown in Figure 3.

There have been few attempts at stock assessment. Holden (1977) used a De Lury method of regressing the log of CPUE on accumulated effort to analyse early CPUE data from the first two KZN net installations to be established. Dudley and Cliff (1993a) attempted something similar using Leslie's method as described by Ricker (1975), to estimate by how much shark numbers were reduced by netting in the 1960s. More recently, OLRAC cc, a firm of fisheries consultants, was asked to analyse the catch and effort database to determine whether it would be possible to predict the amount by which shark numbers (and hence risk of shark attack) may increase if effort were reduced.

Figure 3

Total shark catch taken in the KZN shark control programme

3.4 Sustainability of the resource

The shark control operation constitutes a multispecies shark fishery whose dynamics are not fully understood but the catch seems to be sustainable (Dudley and Cliff 1993a, b). Although landings weight data are incomplete for the early years of the fishery, the numbers of sharks caught indicate that the annual catch has fluctuated about a level of 100t since the 1960s (Dudley 1998). (The catch was lower in the 1950s but there was only one net installation, at Durban, during that decade.) Although the shark catch rate (number of sharks per unit effort) declined steeply in the early years of netting, there has been no evident trend for more than two decades. It may be that the apparent sustainability of the KZN catch is because the nets initially caught the “resident” sharks and now only harvest migrants which encounter the gear (Wallett 1983).

3.5 Discussion

Management requires information pertaining to the sustainability of the catch (including bycatch) and methods of reducing operating costs, catch and bycatch without risking bather safety. In the absence of fishery-independent data, catch and effort data from the programme are likely to continue to be the only means of monitoring the sustainability of the shark catch. Independent census data are used, however, as a means of assessing stocks of the bycatch species of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea). Operating costs and catches could both be reduced through a major reduction in fishing effort (number of nets per beach). A comparison of the shark control programmes of Queensland, NSW and KZN suggests that there is scope for such a reduction in the KZN programme (Dudley 1997). Research efforts to quantify the relationship between fishing effort and degree of bather protection have so far been unsuccessful making specific recommendations about effort reduction difficult. OLRAC has proposed the development of a convection model to simulate shark movement around the nets, and the use of sonic tags to track sharks in order to validate the model. Insufficient funds have precluded this investigation todate.

Research into the use of drumlines as a means of reducing bycatch is yielding promising results, yet the introduction of drumlines would not necessarily reduce costs. If the biological advice is that drumlines be introduced and this is a more expensive policy to implement, the decision would rest on the availability of funds. However, the over-riding factor involved in decisions on possible management actions is, in terms of the NSB's mandate, the provision of protection from shark attack.

3.6 Evaluation of the management process

The executive meets weekly and reports to the board monthly. The executive staff also meet weekly with senior representatives of their respective departments. Thus internal communication is well established.

Although there are strengths when research, management and implementation are all functions of a single organisation, there are also potential weaknesses in terms of complacency and lack of accountability. To safeguard against this, the NSB is subject to external evaluation. It is part of the portfolio of, and answerable to, the provincial Department of Economic Affairs and Tourism. Its financial affairs are audited by the Auditor General of the Province of KwaZulu-Natal. Catch and bycatch data are submitted annually to the Chief Directorate; Sea Fisheries, Cape Town of the national Department of Environment Affairs and Tourism. The NSB is also accountable in terms of service delivery to the coastal local authorities which have protected beaches. Monthly summaries of catch statistics are provided to these authorities and to the provincial government. The NSB is also required to furnish information in response to questions raised by members of the national or provincial parliaments. Trends in catches are published by scientists from the NSB and other institutions. Various environmental monitoring organisations keep themselves informed about the activities of the organisation and the NSB is regularly subject to public, print and electronic media scrutiny.

3.7 Management success

3.7.1 Success of the shark control programme

The programme has been extremely successful in terms of reducing the frequency of shark attack (see Section 2.8.2). There has been no fatality at a netted beach since the first beach was netted in 1952, and only three serious injuries, the last in 1980.

3.7.2 Environmental costs

It is believed that a reduction in numbers of large sharks is the primary mechanism whereby the nets have succeeded in reducing the frequency of shark attacks on the coast of KZN, (Dudley 1997 and references therein). Catch rates of most shark species declined initially but have shown either no trend, or, in the case of the tiger and spotted ragged-tooth shark, an increasing trend, since the mid-1970s (Dudley 1997, Dudley and Cliff 1993a, b). The nets also take a bycatch of dolphins, sea turtles, batoids and teleosts. Turtle and teleost stocks do not appear to be threatened by net mortalities (Dudley and Cliff 1993a, Hughes 1989), but there is concern about the sustainability of the humpback dolphin (Cockcroft 1990). Reflectors of dolphin sonar are being tested as a means of reducing dolphin catches and tests of “pingers” (sound-emitting devices) are imminent (V.M. Peddemors, Natal Sharks Board, pers. comm.). Catch rates of certain batoids may have declined despite a high release rate, but the quality of early data is poor (Dudley and Cliff 1993a). All live animals, including sharks, are released. An assertion that shark netting resulted in a proliferation of small sharks through reduced predation was re-examined by Dudley and Cliff (1993a) and considered to be exaggerated.

3.7.3 Profitability of the programme

The programme creates wealth indirectly through its part in the valuable coastal tourism industry in KwaZulu-Natal cost-benefit analysis has been done but the existence of the programme is regarded by government and industry as essential. Evidence of this is that the programme is funded from these sources.

3.8 Management costs

Total cost of the NSB operation in 1996/97 was R16.2 m ($3.6m), making it the most expensive of the three major shark control programmes. There is, however, a combination of constraints on potential cost reduction which is unique to this programme:

There is no umbrella organisation which could potentially provide boat and equipment storage facilities or supervision.

The process of surf-launching requires a minimum crew of five per boat.

Accommodation is provided for the crew.

If the organisation were to revert only to maintenaining shark nets, costs could be reduced by a considerable margin, with or without a reduction in the quantity of gear deployed per beach. But the NSB offers a multi-faceted service in addition to the basic maintenance of shark nets. Among these services are:

NSB field officers are trained so that captured animals are accurately identified, live sharks and some batoids are tagged and released and physical oceanographic data are collected.

Resources are provided to transport captured sharks and other animals to the NSB headquarters for dissection and the resulting data are published.

Four biologists are employed to ensure a steady output of both basic and applied research on sharks and cetaceans.

The NSB maintains the South African Shark Attack File, which is a component of the International Shark Attack File. The NSB also advises countries with shark attack problems.

NSB research staff sit on various provincial and national committees which address matters ranging from coastal zone policy development to the management of commercial shark fisheries.

As one of the few institutions conducting marine biological research in KZN, the NSB is frequently asked to advise on issues related to the marine environment.

Maintening a public “edutainment” facility, consisting of a modern audio-visual presentation in a large auditorium, a shark dissection accompanied by live commentary, static displays and even a curio shop offering high quality products. In the financial year 1996/97, 30 000 school children and 29 000 tourists visited this facility.

Film companies regularly include the NSB in documentaries referring to sharks and/or to KZN tourism and members of the organisation are interviewed by journalists and writers. The NSB uses these opportunities to convey its philosophy of providing safe bathing in an environmentally sustainable manner and to convey a respect of, and appreciation for, sharks, rather than fear and hatred.

The NSB is on 24 hour call as part of the Aquatic Rescue Co-ordinating Committee, which is responsible for both freshwater and nearshore marine rescue. The NSB is also a member of the Sea Patrol Co-ordinating Committee and South African Search and Rescue. Many of these services are either non-profit or have intangible financial benefits and it is not easy to identify specific cost-recovery and the cost-effectiveness of management. The operation, although undoubtedly expensive, has resulted in the NSB being regarded as a KZN flagship organisation with an international reputation for shark attack prevention and shark research.

4. QUEENSLAND SHARK CONTROL PROGRAMME (QSCP)

4.1 Introduction

The emphasis of the analysis and summary of the QSCP is from the perspective of swimmer protection. The shark “fishery” in this instance is a by-product of a swimmer protection programme installed at popular swimming beaches close to centres of human population. While it is accepted that swimmers at present are not “totally” protected from shark attack on QSCP controlled beaches, the probability of attack is low. This fact is borne out by the history of the programme where there has been no substantiated death due to shark attack on any beach under QSCP control since its inception over 34 years ago. Due to legal and moral responsibilities, fine tuning of gear-types or gear placement must be for the primary purpose of lowering the risk of shark attack on swimmers. The secondary concern of the programme is the reduction of incidental capture of bycatch species, including harmless shark species, which has been an ongoing process within the programme over a number of years. Thus, the shark control “fishery” is not commercially oriented and is fully statesubsidised, for the purpose of reducing the risk of shark attack on humans. Economically, the justification is enhancement of coastal tourism.

4.2 The resource

4.2.1 Species composition of programme

The objective of a “public safety” shark control programme is to catch those shark species and sizes which are potentially dangerous to man. In Queensland this was determined as sharks over two metres in length, and initially a bounty was paid to QSCP contractors for shark of this size or larger. Since the beginning of the programme the QSCP shark nets have been constructed of 20 inch (50cm) mesh which means they are most effective for the larger species. The major categories of shark that were historically considered dangerous to man are the tiger shark (10% of the total sharks recorded), white pointer or great white shark (8%), and the whaler sharks (75%). The latter category is a multi-species grouping which has only been reliably differentiated into species since 1992.

The current species list (Tables 3 and 4) differentiates the bull whaler shark or Zambezi shark (Carcharhinus leucas). This shark was included in the general “whaler” category prior to 1992-3. The Zambezi shark is of particular concern as it occurs at all protected areas along the Queensland coast. is an inshore estuarine species that is highly aggressive and feeds in relatively shallow turbid waters.

4.2.2 Distribution of programme

In September 1962 protective measures consisting of a combination of shark nets and baited drumlines were introduced at the following centres:

The programme was further extended to include the following centres:

Since 1996 the programme could only be extended if local councils pay the costs involved. Currently there are 72 beaches protected, with drumlines or a combination of nets and drumlines maintained by the QSCP, at 10 “controlled” areas along 2000km of tropical and sub-tropical coast.

| QSCP logbooks* | Species | Current QSCP common name |

|---|---|---|

| Pristiophorussp. B | Tropical sawshark | |

| Unidentified Heterodontidae | Unidentified Port Jackson | |

| Heterodontus galeatus | Crested Port Jackson | |

| Heterodontus portusjacksoni | Port Jackson | |

| Chiloscyllium punctatum | Grey carpet shark | |

| 0.03% | Brachaelurus waddi | Blind shark |

| Unidentified Orectolobidae | Unidentified wobbegong | |

| Eucrossorhinus dasyopogon | Tasselled wobbegong | |

| Orectolobus maculatus | Spotted wobbegong | |

| Orectolobus ornatus | Banded wobbegong | |

| 0.72% | Stegostoma fasciatum | Zebra shark |

| 3.23% | Nebrius ferrugineus | Tawny shark |

| 0.01% | Rhiniodon typus | Whale shark |

| 0.08% | Carcharias taurus | Grey nurse shark |

| Unidentified Alopiidae | Unidentified thresher shark | |

| Alopias vulpinus | Thresher shark | |

| 0.65% | Carcharodon carcharias | Great white shark |

| 0.04% | Isurus oxyrinchus | Mako |

| Lamna nasus | Porbeagle | |

| 0.01% | Galeorhinus galeus | School shark |

| Mustelus sp. B | Gummy shark | |

| 0.01% | Hemigaleus microstoma | Weasel shark |

| Hemipristis elongata | Fossil shark | |

| 22.81% | Galeocerdo cuvier | Tiger shark |

| 0.77% | Negaprion acutidens | Sharptooth shark |

| 0.74% | Prionace glauca | Blue shark |

| 0.44% | Triaenodon obesus | Whitetip reef shark |

| 6.57% | Unidentified Sphyrnidae | Unidentified hammerhead |

| 1.08% | Sphyrna lewini | Scalloped hammerhead |

| Sphyrna mokarran | Great hammerhead | |

| Eusphyra blochii | Winged hammerhead | |

| 0.31% | Unidentified Squalomorphea | Unidentified shark |

| QSCP logbooks* | Species | Current QSCP common name |

|---|---|---|

| 46.77% | Unidentified Carcharhinus spp | Unidentified whaler shark |

| Carcharhinus altimus | Bignose whaler | |

| 0.03% | Carcharhinus amblyrhynchoides | Graceful whaler |

| Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos | Grey reef whaler | |

| 0.51% | Carcharhinus amboinensis | Pigeye whaler |

| Carcharhinus brachyurus | Bronze whaler | |

| 3.87% | Carcharhinus brevipinna | Longnose whaler |

| 0.21% | Carcharhinus cautus | Mangrove whaler |

| Carcharhinus dussumieri | Spot-tail shark | |

| Carcharhinus falciformis | Silky whaler | |

| Carcharhinus fitzroyensis | Creek whaler | |

| Carcharhinus galapagensis | Galapagos whaler | |

| 9.12% | Carcharhinus leucas | Bull whaler |

| Carcharhinus tilstoni | Australian blacktip whaler | |

| Carcharhinus limbatus | Blacktip whaler | |

| 0.03% | Carcharhinus macloti | Hardnose whaler |

| Carcharhinus melanopterus | Blacktip reef whaler | |

| 0.87% | Carcharhinus obscurus | Dusky whaler |

| 0.46% | Carcharhinus plumbeus | Sandbar whaler |

| 0.64% | Carcharhinus sorrah | Spot-tail whaler |

| Carcharhinus albimarginatus | Silver tip whaler | |

| Carcharhinus longimanus | Oceanic whitetip whaler |

4.2.3 Associated species either as bycatch or discards

The QSCP database records the capture of non-shark species and the number “released alive” The percentages of bycatch released alive over the 1992–1995 period (Gribble et al. submitted) was:

Rays and harmless sharks such as the whale shark, milkshark, angelshark, Port Jackson shark and wobbegongs are also released alive if possible. It has always been the practice of the QSCP to release bycatch species and in 1992 the QSCP formed volunteer rapid-response marine mammal rescue teams to improve survival of dolphins, dugong or sea turtles entangled in nets.

The major category of bycatch was “rays” at 40% of the total catch (including sharks) recorded in the full 34 year database. Since 1992 the ray category has been differentiated into species (Table 5). As with the shark species list, these rays could potentially be caught by the QSCP although some would be unlikely. Other species incidentally captured by the QSCP over 34 years are dolphins (2% of the total catch), dugong (2%), sea turtles (16%), and a variety of large fish (see Table 6). Only since 1996 have these been listed by species in the database and species identification by contractors is now the subject of ongoing training.

| Species | Current QSCP common name |

|---|---|

| Unidentified Pristidae | Sawfish (ray) |

| Pristis zijsron | Green sawfish |

| Pristis clavata | Queensland sawfish |

| Anoxypristis cuspidata | Narrow sawfish |

| Rhynchobatus djiddensis | White-spotted guitarfish |

| Rhina ancylostoma | Bowmouth guitarfish |

| Unidentified Rhinobatidae | Unidentified shovelnose ray |

| Aptychotrema rostrata | Eastern shovelnose ray |

| Rhinobatus typus | Giant shovelnose ray |

| Trygonorrhina sp. A | Fiddler ray |

| Torpedo macneilli | Torpedo |

| Hypnos monopterygium | Numbfish |

| Unidentified Urolophidae | Unidentified stingrays |

| Gymnura australis | Butterfly ray |

| Unidentified Urolophidae | Unidentified stingaree |

| Unidentified Myliobatidae | Unidentified eagle rays |

| Myliobatus australis | Bull ray |

| Aetobatus narinari | White-spotted eagle ray |

| Rhinoptera neglecta | Cownose ray |

| Unidentified Mobulidae | Unidentified devilrays |

| Mobula eregoodootenkee | Pygmy devilray |

| Manta birostris | Manta ray |

| QSCP logbook* | Common name | QSCP logbook* | Common name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.53% | Dolphin (sp. not recorded) | 0.02% | Crocodile |

| 0.35% | Irrawaddy dolphin | 0.08% | Unidentified fish |

| 1.04% | Dugong | 0.10% | Kingfish (Y-Tail) |

| 2.73% | Green turtle | 0.02% | Lobster |

| 0.35% | Leatherback turtle | 0.10% | Mackerel |

| 3.47% | Loggerhead turtle | 0.30% | Marlin |

| 18.26% | Turtle (sp. not recorded) | 0.03% | Mud crab |

| 0.05% | Barramundi | 0.03% | Puffer fish |

| 0.02% | Black kingfish | 0.10% | Snapper |

| 3.18% | Blue groper | 0.13% | Swordfish |

| 0.02% | Bonita | 0.03% | Toadfish |

| 0.05% | Catfish | 2.13% | Tuna |

| 0.30% | Cod | 0.30% | Whale |

| 0.02% | Conger eel | 64.25% | Ray (see Table 5) |

| 0.02% | Crayfish |

4.3 Development and current status of the programme

4.3.1 Catching methods

The QSCP uses a mixed gear strategy for local reduction of large shark numbers. A combination of baited drumlines and nets have been used since the inception of the programme and drumlines are now the dominant mode of shark population control. This is in contrast to the other two major shark control programmes, the Natal Sharks Board and the NSW Protective Beach Meshing Programme, which use nets exclusively. A mixed gear strategy allows the QSCP flexibility in gear placement. Dreamlines can be deployed in areas that are not suitable for nets and vice versa. Flexibility is also possible in response to environmental concerns. For example, the replacement of nets with drumlines at Bundaberg in 1982 was carried out after concern was expressed for the safety of breeding sea turtles at a near-by rookery.

In 1997 the QSCP deployed a total of 30 shark nets and 340 baited drumlines. Drumlines were deployed at four protected areas and a combination of nets plus drumlines deployed at the other six areas. Each protected area consists of a number of beaches and at each beach the normal amount of gear deployed would be between one and two nets and/or up to six drumlines. Each net is 186m long; consequently any one beach will have a maximum of 372m of net set though the majority of beaches have less. QSCP shark nets are not designed as barries but as a fishing device to reduce the shark numbers.

Each set of fishing gear is serviced every second day unless weather conditions render this impossible. The gear is removed from the water at least once every 21 days for repairs, cleaning or replacement. A complete replacement set of equipment is kept at each location for backup use.

4.3.2 Fleet characteristics, evolution of the fleet and fishing effort

The evolution of the programme has been linked to the expansion of Queensland's coastal tourist industry. Submissions were made periodically by local councils or community groups to the Queensland State Government for a shark control programme to be established at particular beaches. This usually followed a well publicised shark attack or incident. The Government of the day would then direct the QSCP to set an appropriate number of nets and drumlines and to call for tenders for a local contractor to service the gear. The vessels specified in QSCP contracts are high speed catamarans not less than seven metres in length. Small vessels are used in some inshore areas. All vessels comply with relevant Queensland Marine Safety Standards. Currently there are 10 contract districts each with a boat.

4.3.3 Economics of the programme

The programme is a fully subsidised, non-profit, state government operation run as a public safety measure. The QSCP however makes a positive contribution to the coastal tourist industry of Queensland and to marine tourist in general. Queensland's premier beaches are advertised, with justification, as being “fatality free” in regard to sharks. The effect of this contribution could be measured in millions of dollars over the 34 years of the programme's operation. The alternative would be continual shark “scares” with resultant of tourist bookings cancellations. The tourist industry in Queensland is the second largest industry in the state and generates significant income, particularly foreign exchange income, which is taxed both at the federal and state level. QSCP policy is that no shark products will be sold from the programme. The programme enjoys considerable support from industry groups involved in Queensland tourism, as well as from public safety organisations such as the Surf Life Saving Association.

4.3.4 The programme's workforce

The organisation and overall management of the QSCP is centralised in Brisbane but service delivery is developed to local districts and contracted to locals who are in charge of daily servicing of the programme's shark nets and/or drumlines. Each shark control district has a liaison officer (Queensland Boating & Fisheries Patrol) who supervises the contractor and liaises with a local community focus group. These focus groups have representatives of client groups such as local councils, Queensland Surf Lifesaving Association, life guards, community interest groups and conservation groups, and provide community feedback to the district and Brisbane QSCP. Head office staff is limited to one or two employees. There are 10 local district “shark” liaison officers, who also fulfil other normal QB&FP duties, and usually a single contractor per district although he may have an assistant. Therefore between 22 and 30 individuals are involved in the “fishery”.

Staff participation is encouraged through devolving responsibility for day-to-day shark control to the district teams of the shark liaison officer and shark contractor. Annual workshops ensure exchange of techniques and knowledge and maintain consistency of client service between the districts. Central leadership, vision and team cohesion is provided from the head-office management team. Changing client attitudes and needs of the programme are reflected in regular staff training programmes.

4.4 Management objectives

4.4.1 The programme within the context of national fisheries policies

The QSCP could be defined as an inshore fishery and hence comes under Queensland state jurisdiction and the Queensland Fisheries Act (1994), in part, covers the actions of the QSCP. The most pertinent Section of the Act is the requirement for ecologically sustainable development of the fishery. This requirement is also reflected in national fisheries policies. As the QSCP does not sell product it is not covered by the Queensland Fish Management Authority and is exempt from the Authority's licensing regulations.

A number of other policies and/or pieces of legislation affect the activities of the QSCP, the most important being the Queensland Nature Conservation Act (1992) and in particular the Cetacean Management Plan and the Dugong Management Plan. Currently the QSCP is exempt from these management plans. Again the plans reflect national policies on nature conservation and on the protection of endangered species.

There is an overlap of jurisdictions between the state and federal governments because a number of the QSCP controlled beaches are within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park world heritage area which is administered by a federal authority, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA). Historically the inshore areas have been controlled by the state but in 1996 the responsibility of GBRMPA was expanded into these areas. The effect, if any, of this change of jurisdiction on the QSCP is unknown.

4.4.2 Objectives for the management of the shark control programme

Objectives of a shark control programme differ markedly from those of “normal” fisheries in that they are intended to:

These priorities were reinforced at the 1996 ministerial Committee of Enquiry review. Profit is not a motivation as the programme is fully state subsidised but it is financially accountable to the government of the day.

The ongoing management of the QSCP must exhibit two levels of ethical decision making and behaviour. Any changes in the number or placement of shark nets and/or drumlines must be made against a background of the potential risk of such actions to human life, and, while maintaining acceptable levels of swimmer safety, there is an ethical need to reduce unnecessary mortality of bycatch species.

4.4.3 Discussion

There has been a clear and enduring direction given by the management objectives of the QSCP over the years. Even amongst the most vocal conservation groups the concept of protecting human life is considered a powerful argument in favour of maintaining a shark control programme. Management policies, however, are subject to changing community standards and client needs. A permanent feature of the QSCP is client focus groups in each of the programme's 10 controlled districts to provide a venue for local groups to determine a community consensus with regard to shark control. The perception of these needs can diverge, particularly between tourist development and conservation interests. All interest groups have the opportunity to discuss issues and to provide advice to the QSCP. Shark control, and particularly mortality of non-shark species, can be strongly emotive issues and a high degree of diplomacy and judgement is required in dealing with them. Focus groups provide the continuing community feedback the QSCP needs to balance these sometimes conflicting views to determine policies appropriate to the local area. That the QSCP has survived for 34 years is testimony to the balance it has maintained between conflicting client needs and to its dedication to the programme's primary objective of protecting human life.