The impossible development of poor agricultural countries

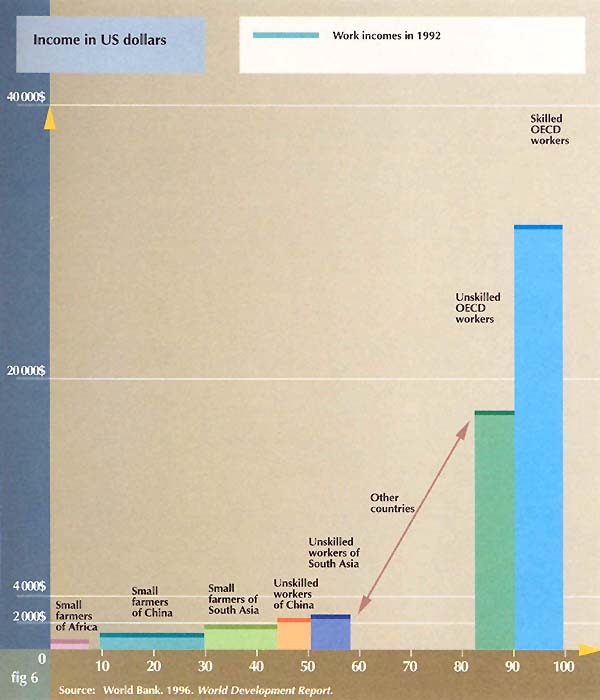

The crisis of deprived small farming communities in developing countries does not only produce a continuing renewal of rural and urban poverty. It also reduces the production capacities of poor agricultural countries and increases their food dependence (there are more than 80 low-income food-deficit countries). Above all, their serious lack of agricultural resources denies these countries a public budget and sufficient foreign currency to modernize, even by falling heavily into debt. They cannot therefore attract enough capital to absorb the build-up of urban unemployment and wages fail to rise much above the level of income of the poor small farming sector. Wages in different parts of the world closely reflect levels of small farmer income (fig. 6).

Insufficient effective demand and the slowing of the world economy

Half of humanity living in rural areas and urban slums finds itself with derisory purchasing power. The UNDP reports that 2.8 billion people live with under US$2 a day, and that 1.2 billion of these have less than US$1 a day. This desperate inability to meet social needs, this colossal under-consumption today constitutes the main factor holding back growth of the world economy.

World production already needs to increase by one-third to feed the current population of 6 billion people without undernutrition, while it will need to almost double to feed the 9 billion people projected in 50 years' time. There is therefore no global agricultural excess production, but rather a dramatic under-consumption that leads to the emergence of surpluses that are difficult to sell and that are in fact often sold at a loss, which only further discourages production.

The regulation of agricultural production through free international trade, which tends to align agricultural prices everywhere to the lowest existing level, is therefore doubly restrictive: on the one hand, it reduces production by eliminating ever-replenished strata of poorly-equipped small farmers and discouraging production by those that remain and, on the other hand, it reduces effective demand by lowering the income of small farmers, other rural inhabitants and rural migrants. Such a mode of regulation reduces both production and consumption and will fail to double production in 50 years or eliminate poverty and undernutrition.

These objectives can only be achieved by mobilizing the world's total land and human capacities. The agricultural revolution stricto sensu can be extended to certain parts of the developing world that have already experienced the green revolution and where motorized mechanization will help increase worker productivity and surface area, without necessarily boosting yields per hectare and production, but this will only reduce agricultural employment and therefore increase rural migration. The agricultural revolution can still enhance yields and production in some regions of the developed countries, but in other regions its excesses will need to be largely remedied. It could be adopted to recover millions of hectares of land that have been abandoned, because of falling real agricultural prices, in regions with some handicap (poor, high-lying, rough, stony, wet or dry terrain, etc.). However, this will only happen if agricultural prices are sufficiently high and if effective world demand actually corresponds to needs, meaning that world poverty is being effectively tackled. This will also only happen on the condition that research and development, which has so far prioritized the privileged regions, redirects a large proportion of its resources towards tailoring biological and mechanical progress to conditions in these regions.

Similarly, the green revolution in its classic form can still produce yield gains in some regions and penetrate further into a number of relatively favourable regions, but it will also have to rectify excesses in other regions. But all this will do nothing to resolve the problem of extreme impoverishment and undernutrition of hundreds of millions of rural inhabitants and small farmers. Not only will research and development need to be massively redirected towards disadvantaged regions and small farms but their economic viability will also need to be assured if they are to benefit from a “second green revolution”. This presupposes significantly raising agricultural prices that are presently far too low to permit investment or progress, or simply to ensure survival beyond the duration of a project.

Figure 6

Scale of wages in the world in 1992