More than any other Centre within the CGIAR, IPGRI relies on partnerships and networks to carry out its research, capacity building and related activities. As a scientific research institute without laboratories or experimental fields, IPGRI has had "by necessity" to work through partners using partners' facilities to achieve its goals. IPGRI has employed partnerships and networking as means of leveraging additional financial and other resources, thus multiplying the efficiency of investment of its own resources.

Networks are generally expected to deliver results more efficiently and effectively than any partner operating alone. However, working through networks also has drawbacks. Transaction costs can be high. Negotiated decision making takes more time and often results in compromise solutions. Coordination of international networks can be expensive and, after the project funding ceases, networks can be unsustainable.

A study conducted by IPGRI in 2002[15]: analysed three well-established partnerships in its own portfolio COGENT; in situ conservation of agricultural biodiversity in Nepal; and traditional leafy vegetables in SSA. The results underscored three important lessons. First, very tight coordination on the part of IPGRI may not be sustainable or desirable in the long run. Second, partners must be carefully selected to ensure maximum benefits. And third, costs of partnership must be carefully weighed against benefits. Partnerships are worthwhile where they are likely to deliver desired outcomes cost effectively.

Nevertheless, partnerships conducted and managed through networks are often better able to achieve multiple goals simultaneously. If carefully planned with a view towards sustainability, they can serve as important conduits for long term, scaled up impact. IPGRI considers potential for sustainability, multiplier effect and excellence as a major part of their criteria for partner selection.

IPGRI's key institutional partners continue to be NARS agricultural research institutes, genebanks and universities, international organizations, regional centres of excellence, PGR research organizations and networks, (formal and informal). To a more limited extent, IPGRI also has collaborative relations with NGOs, private companies and farming communities. In most cases, collaborations with these latter groups have been designed as part of multi-stakeholder implemented activities that often also involve NARS partners. Among IPGRI's projects, the In situ project has presented the most opportunities for this type of collaboration, which has slowly increased in recent years.

Around the time of the last EPMR, IPGRI had significant involvement in 11 regional networks and nine international commodity focused networks. IPGRI continues to be engaged with these. During the period under review, several new regional and sub-regional PGR networks and commodity specific networks have been created with varying degrees of IPGRI engagement. Consistent with the recommendations of the GPA, IPGRI has given priority to facilitating the establishment of new PGR networks in regions where they did not previously exist. Likewise, increased effort has gone into strengthening existing networks or integrating countries not presently served by them. These networks, particularly the newly established ones, will continue for some time to require technical assistance and capacity building support.

However, unlike in the past when IPGRI assumed direct responsibility for network coordination and management, e.g. in COGENT and even funding, IPGRI now mostly provides only technical backstopping support, e.g. in APFORGEN and EAPGREN. Primary responsibility for assisting these networks is increasingly being assumed by regional centres of excellence or leading network members. This strategy of mobilising strong partners to assist weaker partners not only reduces the demand on IPGRI, but also elevates the profile of local centres of excellence and promotes greater collaboration among partners in the region. Such an approach is expected to instil a greater sense of ownership, responsibility and participation in network activities among partners, which are of key importance to future network sustainability. Thus the Panel commends IPGRI for adopting this approach and strongly endorses its continuation. The Panel also recognizes IPGRI's remarkable contribution to the implementation of the GPA recommendation on PGR network strengthening during the period under evaluation.

Letters of Agreement (LoA) are the principal legal instruments through which IPGRI engages other organizations or individuals for partnership in research and research related activities. Despite the contractual arrangements, the relationship of IPGRI with LoA partners typically goes beyond simple outsourcing or hiring external research capacity. Under these arrangements, partners make contributions based on their core competencies. In return, as well as from LoA funding, they receive capacity building support, access to data and information and links to IPGRI's extensive network of local and global partners. Although LoAs do not encompass all of IPGRI's partnerships, they are a good indicator of the Institute's work programme and of the profile of its collaborators.

A consultant's evaluation[16] conducted in 2003 on IPGRI's LoA profile reveals striking trends and implications for managing IPGRI's partnerships. Between 1996 and 2001, IPGRI issued 1 222 LoAs to 630 different partner institutions in 127 different countries around the world. Total funding made available through LoAs during the period amounted to US$18.9 million, an average of more than US$3.0 million per year. This corresponds to around 15% of IPGRI's total annual expenditure. The number of LoAs increased while the average amount per LoA decreased from an average value of US$29 460 per LoA in 1996 to US$15 478 in 2001 (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 - IPGRI LoA resources by partner and period 1996-2001

|

Partner Category |

1996 |

2001 |

Total funding for |

Average |

Share of LoA |

LoAs |

|

CGIAR |

512 597 |

67 670 |

2 053 838 |

26 331 |

11% |

78 |

|

Individuals |

212 959 |

23 137 |

641 715 |

6 054 |

3% |

106 |

|

National research institutions |

686 064 |

1 709 004 |

9 216 805 |

13 455 |

49% |

685 |

|

Non-governmental organizations |

280 300 |

315 989 |

1 166 429 |

15 763 |

6% |

74 |

|

Private companies |

61 146 |

15 576 |

322 637 |

11 950 |

2% |

27 |

|

Regional networks or associations |

104 800 |

84 664 |

417 981 |

11 297 |

2% |

37 |

|

United Nations |

|

1 010 |

268 510 |

89 503 |

1% |

3 |

|

Universities or other educational institutions |

1 353 288 |

456 867 |

4 799 878 |

23 076 |

25% |

208 |

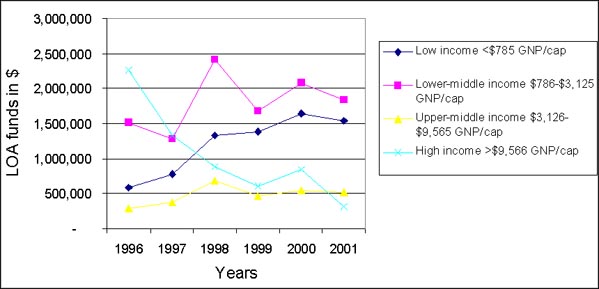

More than half of LoAs signed and about half of the funds expended during the review period were directed towards partnerships with national research institutions while universities and other educational institutions received 25% of the funds. Increasingly, LoA funding was also directed towards lower and lower-middle income countries with annual per capita GNP below US$3 125 and away from higher income countries which in the past received the major share of LoA contracts (Figure 6.1). LoA contracts to individuals dropped dramatically. The shift towards smaller contracts to lower income countries, usually with less developed capacity, demonstrates IPGRI's strategy of using LoAs as mechanisms for delivering funds and targeted assistance where they are most needed. However, this raises questions about quality of the research output and intensity of IPGRI staff time commitment to ensure that products from these collaborations meet quality standards.

The Panel fully appreciates this difficulty. More attention to selection of LoA partners based on a realistic assessment of their requirements and potential could facilitate closer matching of partner institutions with IPGRI's output expectations and capacity development objectives. Mobilising strong regional partners to provide technical support to needy countries, as already planned, could also mitigate this difficulty. Where resources allow, the Panel suggests that IPGRI also consider posting additional regional staff to more effectively fill gaps, help keep staff work load within reasonable bounds and ensure that research quality standards are maintained (also see recommendation 9).

IPGRI's use of the LoA mechanism is also contributing to the production of outputs targeted by the CGIAR system. During the period under review, around 21% of LoA funding was used to enhance NARS capacity. However, the bulk of funding, almost 60%, supported germplasm collection and improvement, 15% was used for activities to promote sustainable production systems and the rest was used for policy studies (Table 6.2).

The number of collected accessions and collection activities undertaken by IPGRI's national and regional partners is one indicator of the effectiveness of this approach. Data from IPGRI regional offices reported a total of 9 962 accessions during the period from 1996 and 2002. About two thirds of these accessions, 6 571, were from APO, of which 5 067 were coconut samples. Through its regional offices, LoA contracts also supported courses, internships and individual training (see Section 5.1.4).

Figure 6.1 - Development of LoA funding by recipient countries’ income groups

Table 6.2 - LoA assessed by CGIAR output categories

|

Type of activity |

LoA Funding |

CONTRIBUTION TO CGIAR OUTPUTS (US$) |

||||

|

Germplasm |

Germplasm |

Sustainable |

Policy |

Enhancing |

||

|

Collecting |

381 141 |

|

381 141 |

|

|

|

|

Consultancy (*) |

212 075 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ex situ conservation |

488 539 |

|

488 539 |

|

|

|

|

Germplasm characterization and evaluation |

2 897 934 |

2 897 934 |

|

|

|

|

|

Germplasm health |

1 309 060 |

1 309 060 |

|

|

|

|

|

Germplasm utilization |

2 733 588 |

|

|

2 733 588 |

|

|

|

In situ conservation |

4 616 909 |

|

4 616 909 |

|

|

|

|

Policy and legislation |

763 461 |

|

|

|

763 461 |

|

|

Publications and public awareness |

833 092 |

|

|

|

|

833 092 |

|

Purchase (*) |

136 394 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Research unspecified (*) |

378 668 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seed technology |

633 638 |

633 638 |

|

|

|

|

|

Software development data management and dissemination |

937 994 |

468 997 |

|

|

|

468 997 |

|

Training |

1 312 413 |

|

|

|

|

1 312 413 |

|

Workshop/meeting |

1 278 888 |

|

|

|

|

1 278 888 |

|

Totals |

18 913 793 |

5 309 629 |

5 486 588 |

2 733 588 |

763 461 |

3 893 390 |

|

Contribution LoAs to CGIAR outputs |

|

29% |

30% |

15% |

4% |

21% |

|

Comparison with IPGRI Research Agenda, 1999-2001 averages (in million US$) |

|

3.1 |

8.1 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

6.6 |

|

Shares of CGIAR Outputs |

|

13% |

35% |

12% |

12% |

28% |

The Panel recognizes the significant outputs generated through IPGRI's collaboration with national and regional partners. The Panel endorses IPGRI's continued use of LoAs in the manner and direction already described. However, the Panel strongly urges IPGRI to guard against unproductive LoA partnerships and to take appropriate steps to ensure that the research and related outputs emanating from these partnerships are of sufficiently high quality.

Apart from its leadership role in the SGRP (see Section 5.2.2), IPGRI has a wide range of collaborative arrangements with other CGIAR Centres. IPGRI staff is hosted by seven other Centres: ICRAF (SSA office in Nairobi); IITA (WCA office in Benin); ICARDA (CWANA office in Syria); CIAT (AMS office in Colombia); ICRISAT (APO office in New Delhi); ICARDA (CWANA office in Tashkent); and IRRI (INIBAP-AP office in Manila). IPGRI also shares staff with IITA and IFPRI. IPGRI has an Honorary Fellow at ILRI. In addition, IPGRI participates in several Systemwide initiatives coordinated by other Centres.

IPGRI has been formally collaborating with CIFOR and ICRAF on forest genetic resources since 1993. With recent programme restructuring and staff changes in these Centres, the terms of collaboration need to be reviewed (see Section 3.2 and Recommendation 3). The Rainforest Challenge Programme initiative and other nascent forestry focused programme developments within CGIAR provide fertile areas for further IPGRI collaboration with these Centres.

Collaboration with IFPRI, primarily through shared staff, has focused on economic and policy dimensions of in situ and ex situ PGR conservation. The relationship appears to be working although IPGRI could take greater advantage of IFPRI's recognized strength in socio-economic and policy analysis.

Relations with CIP, CIAT, ICRISAT, ICARDA and other Centres have been largely project or activity driven, or in the context of their common participation in crop specific networks. IPGRI has also worked in partnership with ISNAR on training and has been in consultation with ISNAR on impact assessment tools and methods. In recent years, IPGRI has been providing assistance on an ad hoc basis to other institutions in framing and designing impact assessment processes and instruments. IPGRI's budding expertise in this area is beginning to be recognized within the CGIAR.

Feedback from other Centres in response to a Panel survey for this EPMR indicates a high regard for IPGRI's contribution to the CGIAR system, especially its leadership role in the SGRP.

FAO has been and continues to be, one of IPGRI's most important partners. Since 1990, IPGRI has collaborated with FAO on agricultural PGR under the terms of their MoU on Programme Cooperation and their joint programme on forestry. FAO is represented as a non-voting ex officio member on IPGRI's Board and Executive Committee (see Section 7.2). IPGRI-FAO joint activities have included research and training, co-sponsorship of meetings and workshops and preparation and dissemination of publications. The development, negotiation and now the monitoring of implementation of the GPA have been the major focus of IPGRI-FAO collaboration over the past decade. Through a letter of agreement with FAO, IPGRI has developed and is currently pilot-testing the GPA National Information Sharing Mechanism in Kenya and Ghana. FAO and IPGRI have worked in partnership to establish the GCT and FAO has offered to temporarily host the Trust until it moves to its permanent location. (See Section 5.2.5.)

FAO views its relationship with IPGRI since the last EPMR to have been excellent. FAO is also of the view that its future collaboration with IPGRI should focus on monitoring the implementation of the GPA and on assisting countries in the implementation of the provisions of the ITPGRFA and, during the interim period until its entry into force, on providing information that will facilitate rapid ratification. In addition, FAO expressed interest in possible collaboration with IPGRI on animal genetic resources. (See Chapter 11)

Currently, IPGRI has limited formal collaborations with NGOs although IPGRI-NGO partnerships are gradually expanding especially on a few in situ activities. IPGRI is to be commended for having gained acceptance and credibility among some sections of the global NGO community through its balanced and skilful role in the Information Technology negotiations. However, IPGRI remains unknown throughout most of the sector. Partnership with carefully selected NGOs would greatly add value to IPGRI's work, especially in national projects that have very explicit development objectives (see Section 2.4). This would help IPGRI set reasonable bounds on its involvement in development activities and therefore concentrate its energies on research, technical assistance and related activities that it is best configured and able to undertake. If IPGRI takes on work related to biosafety issues and genetic technology related risk assessment, it would be important also to have NGOs involved in this exercise. NGOs can provide alternative perspectives and add to the credibility of IPGRI's efforts in this area.

IPGRI is slowly developing collaborative relations with the private sector, primarily with small entrepreneurs and private companies that cater to domestic markets. While private companies and entrepreneurs are seldom directly concerned with conservation, they are often important users of PGR. As IPGRI adopts a production to consumption commodity chain approach in its field projects, the participation and involvement of the private sector will be increasingly necessary. Much of the research and development on genetic modification of the major crops is done by the private sector, particularly the large companies. Hence, they are an important player in PGR research. Thus the Panel suggests that IPGRI continue to proactively engage with their target segments of the private sector where this is in keeping with its goals and ethical standards[17].

IPGRI was established as a legal entity under international law in October 1991 and recognized as such by the host country, Italy, through the parliamentary ratification of IPGRI’s Establishment and Headquarters Agreements in January 1994.

The Government continues to be very supportive of the Institute. Strong links have been established with many Italian institutions. In 1999, the Government provided special financial support towards the cost of moving IPGRI’s Headquarters to Maccarese, near Rome, which were inaugurated by the President of the Republic of Italy. Strong and very productive links have been established with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Italy, as one of the world’s leading countries when it comes to PGR, has increasingly recognized the crucial role IPGRI is playing in this area.

Recently, IPGRI submitted a request for an additional annual contribution towards the cost of operating IPGRI’s Headquarters in Italy. The request is based on the fact that other international organizations with headquarters in Italy (such as FAO, WFP, IFAD and IDLO) have this provision built into their host country agreements. IPGRI’s request is being given positive consideration at a very high level. However, the process of legalising such contribution is likely to be complex. If approved, it would be of enormous strategic importance to IPGRI.

As part of this EPMR, the Panel used a survey to get partners' and stakeholders' assessment of IPGRI's performance. The Panel received 103 responses out of over 500 questionnaires that were sent electronically to IPGRI's institutional partners and PGR contacts. Despite the relatively low response rate and the uneven responses across regions, the respondents represented a good approximation of IPGRI's partnership profile. Around 37% were from NARS and PGR networks, 22% from universities, 15% from genebanks, 12% from international organizations, 7% from governments and 7% from NGOs. Although the results can only be interpreted with caution, they strongly suggest broad patterns that IPGRI would do well to follow up.

The survey consisted of four questions. The first question asked the respondent to assess IPGRI's global contribution through research, training, technical assistance, networking, policy and legislation and its other regular activities. The second question asked whether or not IPGRI meets expectations of the respondent's organization with respect to these activities. The third question asked the respondent to assess IPGRI's credibility and reputation among different stakeholder groups. And, the fourth question asked whether or not the respondent's organization has adequate opportunity to participate in setting IPGRI's research, training and outreach agenda.

Responses to the first question indicate a highly positive assessment of IPGRI's global contribution, (Table 6.3). Overall, assessment of IPGRI's contribution through its regular activities is seen to be significant or very significant. However, interestingly, respondents who have not collaborated with IPGRI and hence have little first hand experience with the Institute, tended to have less favourable assessments. IPGRI's contributions in research, technical assistance, training, workshops and information provision were especially highly rated. IPGRI's contribution to policy and legislation, while also seen as very positive, was assessed to be relatively less significant. IPGRI's contribution was similarly very positively assessed in all regions, although less so in the Americas. NGOs gave the least positive assessment; where 40% assessed IPGRI's global contribution as not significant.

Table 6.3 - IPGRI Stakeholder Survey; Responses to Questions 1 and 2 by Region and by Stakeholder Group (%)

| |

Region |

Stakeholder group |

|||||||||

|

Americas |

Africa |

APO |

CWANA |

Europe |

banks |

NARI |

NGOs |

Univ. |

Int. |

Govrn. |

|

|

Question 1: What is IPGRI’s global contribution? |

|||||||||||

|

Very |

29.9 |

30.7 |

56.0 |

40.0 |

49.8 |

58.3 |

45.5 |

12.5 |

47.2 |

52.8 |

25.9 |

|

Significant |

48.5 |

58.4 |

35.2 |

48.0 |

43.6 |

35.8 |

40.3 |

50.0 |

48.4 |

43.1 |

65.5 |

|

Not |

21.6 |

10.9 |

8.8 |

12.0 |

6.6 |

5.8 |

14.2 |

37.5 |

4.4 |

4.2 |

8.6 |

|

Question 2: Does IPGRI meet your organization’s expectations? |

|||||||||||

|

Yes |

61.0 |

81.6 |

72.4 |

77.2 |

79.6 |

84.6 |

71.4 |

63.0 |

77.6 |

94.0 |

47.8 |

|

No |

39.0 |

18.4 |

27.6 |

22.8 |

20.4 |

15.4 |

28.6 |

37.0 |

22.4 |

6.0 |

58.2 |

Based on responses to the second question, IPGRI appears to meet expectations, particularly those of its main partners. However, governments and partners in the Americas appear less satisfied. Responses suggest that this may be due in part, to unmet expectations regarding funding. Responses from NARS also indicated some unmet expectations with respect to research and technical assistance.

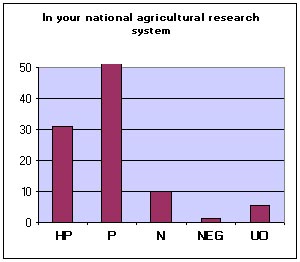

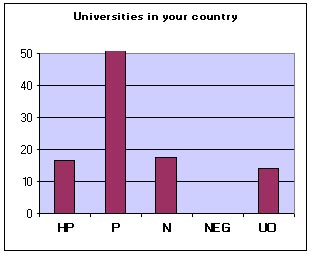

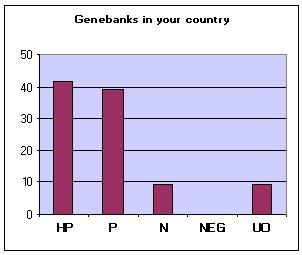

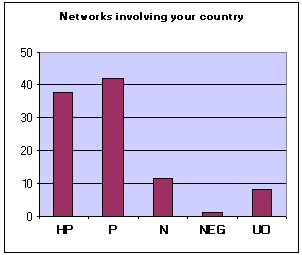

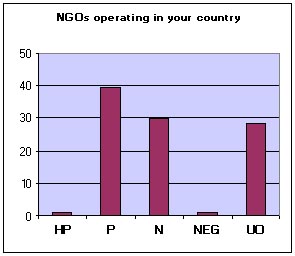

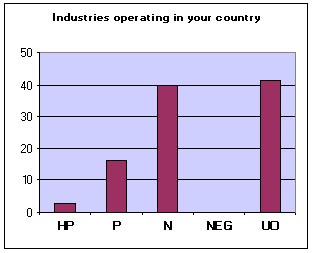

Responses to the third question strongly indicate that IPGRI has credibility and enjoys a positive, or non-negative reputation among most stakeholder groups (Figure 6.2). Not surprisingly, IPGRI seems to be relatively unknown among the private industrial sector and, to some extent, among NGOs. Thus, the Panel suggests that IPGRI's public awareness efforts try especially to reach NGOs and the private sector, as discussed above.

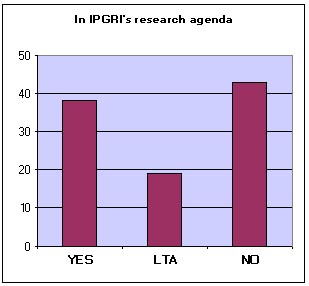

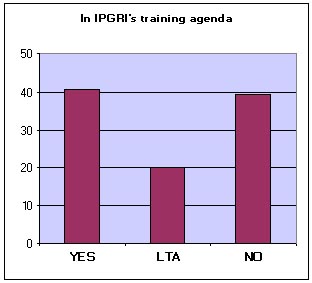

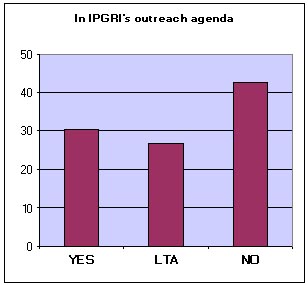

Responses to the fourth question are disappointing. Sixty percent or more of the respondents indicated that they had less than adequate or no opportunity to participate in IPGRI’s agenda in research, training and outreach. The Panel strongly suggests that IPGRI follow up these responses, particularly from NARS, who should have the opportunity through their involvement in regional networks. IPGRI relies principally on partnership and collaboration as its modus operandi. It is possible that the avenues for greater participation by partners need to be provided or strengthened.

Panel believes that IPGRI needs to review its planning and priority setting practice and mechanisms to facilitate greater participation by partners and stakeholders in setting the agenda for its research, training and outreach.

Figure 6.2 - IPGRI Stakeholder Survey Responses

Question 3: What is IPGRI’s credibility and reputation?

HP = Highly positive; P = Positive; N = Neutral; NEG = Negative; UO = Unheard of

Question 4: Does your organization have adequate opportunity to participate in setting priorities?

LTA = Less than adequate

In summary, the Panel commends IPGRI for its performance and contributions that its partners and stakeholders evidently regard very highly. That IPGRI has managed to build its credibility and to maintain a positive, or at least non-negative, reputation in an increasingly contested area of work is also quite remarkable. However, IPGRI needs to increase its engagement with NGOs and the private sector. Where appropriate and consistent with the Institute's ethical principles, IPGRI could also benefit from greater links with the private sector.

|

[15] Robinson, J. and Watts,

J. 2002, Nature and effectiveness of partnerships across several IPGRI

coordinated projects. IPGRI, Rome. [16] Groenewold, J.P. 2003, Evaluation of the IPGRI Letters of Agreement Database for the years 1996-2001. IPGRI, Rome. [17] IPGRI's Statement of Ethical Principles, BOT 14 papers. |