Step by Step: Scaling-up Agricultural Investment

Transforming rural lives in Bangladesh

Like millions of farmers in Bangladesh, Renu Bala lives at the mercy of annual floods. Because of the low-lying topography, almost 18% of the country is inundated during the monsoon season every year. During extreme events over half the country can be flooded.

“Our farm and the paths are completely drowned by the water” she explains, “it’s very challenging to farm here.”

Renu Bala lives in Panjor Bhanga village on the banks of the River Teesta, in northern Bangladesh. When the floods come she moves her family, possessions and animals to higher ground. Since 2014, her animals include 10 Friesian dairy cows. They provide milk for her family and an important source of extra income.

Renu Bala milking one of her Friesian cows with her husband (left) and members of the Panjor Bhanga Women’s Milk Cooperative collecting the morning milk (right).

Panjor Bhanga, Bangladesh, October 27, 2017.

To sell milk in larger quantities and at higher prices, Renu Bala established a dairy cooperative with 30 other local women. The group is known as Panjor Bhanga Mahila Dugdha Samabay Samity, or Panjor Bhanga village Women’s Milk Cooperative Association.

Obtaining finance to invest in higher milk-producing breeds is a major challenge for the women. Individually they have no collateral to secure loans. The women also lack experience in looking after, feeding, immunizing and breeding cattle. Between 2014 and 2016, Renu Bala and the Cooperative received training from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) through the Integrated Agricultural Productivity Project (IAPP).

“I learnt so much about cattle breeds, and about how to take a loan from a bank” she says “and we have also learnt a lot from the exchange visits to larger farms and farmer organizations”.

With this support, the women were able to use the Cooperative as collateral for a low-interest loan of USD 13 000 to invest in the dairy business. The investment is now paying dividends. Having paid back the loan within a year, the group received a second loan.

Milk production is now over 200 litres per day and they have secured buyers in the local town and from a milk processing company. The Cooperative has united the village women, increased their incomes and improved their cash reserves to provide food for their families.

Investing at scale

Renu Bala’s story is one of many.

Rural and agricultural development in Bangladesh has dramatically reduced poverty. According to the World Bank, agriculture accounted for 90 percent of the reduction in poverty between 2005 and 2010 [i]. With almost half of the national workforce employed in agriculture this is not surprising.

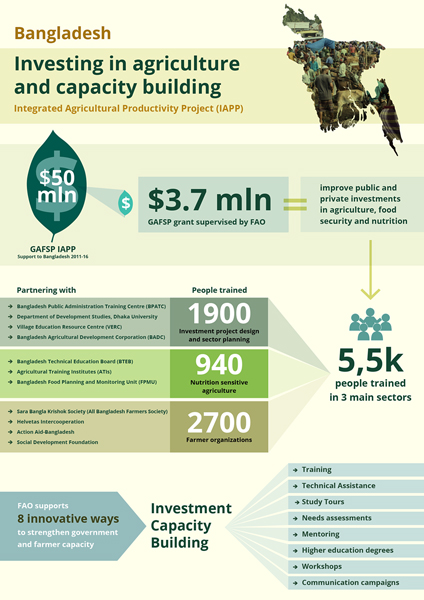

In 2010 the Bangladesh Government, with technical and methodological support from FAO, developed its Country Investment Plan (CIP) for agriculture, food security and nutrition. This was done by engaging a broad spectrum of actors in the public and private spheres. This national 5-year Plan (2011 to 2016) outlined the need for USD 7.8 billion in investments. To be effective, the CIP also emphasized the need to improve how public and private entities design, manage and monitor investments.

Rice, Bangladesh’s staple agricultural crop, growing in paddy fields near Jatrapur, Bangladesh. October 25, 2017.

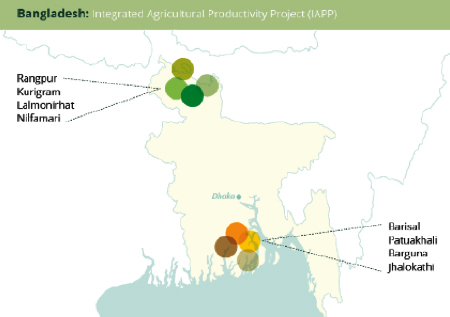

IAPP was the first initiative to work with the Government to address these challenges in the CIP, and was the Project which Renu Bala later benefitted from. The IAPP was financed by the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program (GAFSP) and focused on improving agricultural productivity in 4 economically depressed northern districts and 4 southern districts of the country - areas that are particularly vulnerable to flooding, drought and tidal surges. The USD 50 million IAPP consisted of investing in water management, technology development and dissemination (supervised by the World Bank), while capacity development aspects were implemented by FAO.

Benoist Veillerette, FAO senior economist and FAO Bangladesh GAFSP coordinator (left) Nichola Dyer, programme manager of GAFSP (right).

FAO headquarters, Rome, Italy. October 10, 2017.

Nichola Dyer, programme manager of GAFSP, explains that

“the IAPP in Bangladesh worked to enhance agricultural productivity by testing and piloting technologies, good practices, and training with a high level of focus on climate resilient approaches”.

Whilst the IAPP budget was only a fraction of the national CIP investment, it was designed to be scalable and long-lasting. As she emphasises

“scale is crucial, because if we can scale up good practices, build investment capacity, and empower smallholder farmers then that will be transformative for the whole economy including for the development of its private sector.”

The capacity development element of the IAPP, which was led by the FAO Investment Centre, sought exactly this. As Benoist Veillerette, a senior economist at FAO, explains

“drawing on its long standing presence in Bangladesh and agricultural investment expertise, FAO sought to improve the way in which both the public and private sector invest in rural livelihoods. This is essential to achieve a food secure Bangladesh, with rising levels of nutrition”.

In addition to working with staff in 11 Ministries (e.g. Agriculture, Planning, Finance, Fisheries & Livestock, Disaster Management and Relief, Women and Children Affairs, Food and Local Government Rural Development & Cooperatives) and other public agencies, FAO also ensured that farmer organizations were involved in the many investment capacity development activities.

Investing in farmer organizations

For Abdul Jabbar, scale is also essential.

“More than 80% of farmers in Bangladesh struggle a lot” he explains“ that is why it is essential we work together”.

Abdul Jabbar, President of the SBKJ farmers society in his paddy field (left) and meeting of members of the SBKJ (right)

Jatrapur, Bangladesh, October 25, 2017.

With average farm holdings of less than one ha, and many below 0.2 ha, working together makes sense . Farmers can jointly buy in bulk at lower prices and sell in bulk at higher prices. It also facilitates access to credit, the exchange of new and better farming practices, and puts smallholders in a stronger position to negotiate with public and private actors in the value chain, including large private sector companies.

Like Renu Bala, Abdul Jabbar farms in the Rangpur District of northern Bangladesh. For him, the FAO capacity development component of the IAPP came just at the right time.

“With assistance from FAO I have been able to encourage the farmers in my area. We have strengthened our farmer organization and created new business opportunities.”

Abdul Jabbar is President of Sara Bangla Krishak Jote (SBKJ) or the All Bangladesh Farmers Society. The Society was formed in 2014. IAPP support was critical explains Abdul Jabbar,

“FAO mapped all the farmer organizations around the country. They also provided guidance on how to register a Society and advice on governance, accountability, planning and financial transparency”

In the absence of an autonomous national farmer network, the SBKJ now brings together and supports 44 local farmer organizations under one country-wide umbrella.

These farmer organizations play an important role in investment planning and implementation. Between 2014 and 2016 more than 2,600 farmers and agricultural leaders benefited from IAPP capacity development.

FAO offered a diverse series of innovative approaches. These ranged from leadership mentoring and exposure visits (both in Bangladesh and to the Philippines, Kenya and India) to expert workshops, retreats and assistance with agricultural technologies. This has strengthened farmer networks, led to new farming businesses (see Abdul Jabbar’s story) and brought farmers together in surprising ways.

Strengthening public capacity to invest

“Whatever we learn from seeing and reading we can easily forget, but when you do something it is difficult to forget”

explains Dr Mahmudul Hasan, the former Director of the Bangladesh Public Administration Training Centre (BPATC).

Dr Mahmudul Hasan (left), former director of Bangladesh Public Administration Training Centre (BPATC), which trains between 1,400 and 1,600 new civil servants every year. Rehana Parvin (right) in her office in the Department of Agricultural Extension in Dhaka, Bangladesh, October 29, 2017.

Besides helping farmers’ organizations, the IAPP support to government agencies emphasised applied learning and working with national training institutes such as the BPATC, Dhaka University and Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB). Benoist Veillerette explains that the

“FAO partnerships with these education institutions was essential. Working together helped ensure the sustainability of our capacity development activities as our courses were integrated into their permanent curriculum.

Between 2014 and 2016 over 1800 government employees took part in the courses and there will be more after project completion.

The hands-on learning style was new to many, as Dr Hasan explains

“the FAO investment training took a really practical approach. All the students took part in discussions, played an active role, and used examples from the field…from real life projects”.

The courses focused on each stage in the investment cycle, from project design and implementation through to monitoring and evaluation. Leadership modules, as well as study tours, team building retreats and “training of trainers” workshops were an integral part of IAPP. Working this way proved very popular, as Dr Hasan emphasises “the course ratings by the participants were very high”.

For Rehana Parvin, who is a planning specialist in the Department for Agricultural Extension, at the Ministry of Agriculture, the training was invaluable.

“After the training in economic and financial analysis I have been calculating the Net Present Value, Benefit Cost Ratio and Internal

Rate of Return for all the new project designs.”

This is resulting in more thorough planning and improved designs for agricultural investments. In addition she has changed her approach to investment planning:

“now we always design the project from bottom up with our

colleagues in the field”.

The benefits of the capacity development were felt country-wide.

For the first time nutrition and food preparation topics were mainstreamed in the syllabus of 240 Agricultural Training Institutes.

IAPP project staff, particularly Community Facilitators and Field Assistants, also

received investment training to assist them in their work with hundreds of

thousands of livestock, fish and crop farmers.

For farmers like Renu Bala and Abdul Jabbar, who are working in remote parts of the country, this all adds up to more public and private support and new opportunities for their farmer organizations.

Mike Robson, the former FAO Representative in Bangladesh (2013-16), emphasizes that

“improving the effectiveness of investments in agriculture, food and nutrition is critical. Working with the Government of Bangladesh, the IAPP made considerable progress in improving both national and local capacities to design, implement, monitor and evaluate investments. By partnering with training institutes and the agricultural extension services, and through refining curricula and training trainers, the impacts of this 5-year Project will be seen for years to come”.

Renu Bala calculating milk receipts for the Panior Bhanga village women’s milk cooperative.

Follow-up efforts are however also needed to refresh the knowledge acquired and to support fledgling initiatives. The GAFSP-funded Missing Middle Initiative (MMI) seeks to do this. This 3-year Initiative aims to support 50 Bangladesh farmer organizations (approx. 10,000 women and men) and their members to access financing, innovative technologies, new value chains and markets.

In 2018, FAO and the Government of Bangladesh will begin implementing the MMI in close collaboration with SBKS, the Asian Farmers’ Association (AFA) and local partners. Following the success of Panjor Bhanga women’s dairy cooperative, Renu Bala was elected as an MMI spokesperson. She, along with many others, will ensure that the MMI results in long-term benefits and business opportunities for Bangladeshi farmers.

Investing in agriculture can transform lives, reduce hunger and malnutrition, and eliminate poverty. Working with international partners, FAO has contributed to over 2,000 agricultural and rural investment strategies, policies and programmes in more than 170 countries. The majority of this work is carried out by the FAO Investment Centre.