Innovation is fostered by information gathered from new connections; from insight gained by journeys into other disciplines or places; from active, collegial networks and fluid, open boundaries. Innovation arises from ongoing circles of exchange, where information is not just accumulated or stored, but created. Knowledge is generated anew from connections that weren’t there before. (Wheatley, 1992)[4]

Making a shift towards a development philosophy that emphasizes community engagement and collaboration requires new policy frameworks, institutional buy-in in the form of new skills and attitudes by professionals, and a willingness to innovate. The shift in development thinking has been taking place around the world; the accomplishments that are emerging point to some undeniable facts:

That change is possible

There are neither standard solutions nor blueprints

There is a constant need to innovate

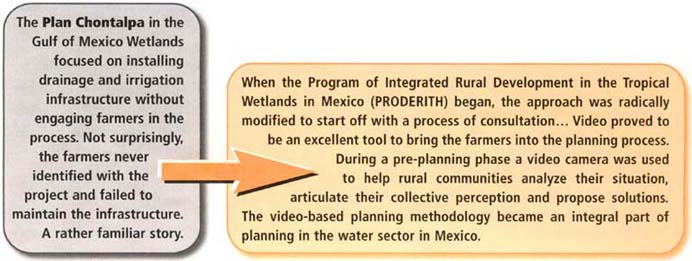

The following Mexican experience illustrates the significance of the shift:

Through the years of Proderith, these experiences had a profound impact. The Director General of the National Water Commission went on record to announce that the government of Mexico would never again build any infrastructure without first involving the people whom the program is intended and who are required to maintain infrastructure (FAO, 1992).

Our [communication] costs have remained below 1.5% of the global investment and the benefits we have had during the first phase of the project have demonstrated to us that enhanced project implementation and rapid transfer of technology have contributed to the fact that our internal rate of return has been higher than initially planned. That is 7% higher than initially planned for the project.

Fernando González Villarreal, DG,

National

Water Commission, Mexico.

The Mexican example has become a popular case study[5]; what is most relevant from that experience is the fact that a large governmental system was able to experiment with new approaches. In essence, they innovated and created a precedent.

Development managers today struggle with how to make the shift in their own contexts; there are no blueprints but many common themes.

Managers do not always initiate change on their own; outside pressure is often the trigger for innovation. In the Mexican example, it was failure in programme implementation that stimulated change. In other cases, external threats have been a powerful trigger to propel change and innovation.

In a DFID study that started in 1993, it became clear that natural resource scientists only began paying attention to communication when the very existence of their programmes became dependent on being able to show impact in the field.

The realization that people must be involved in program decision-making is beginning to be shared across donor agencies. A recent World Bank published handbook for Poverty Reduction Strategic Plans (PRSP) included a chapter on Strategic Communication Planning. This came about through donor consultation around the PRSP process. The working group for PRSP challenged the Bank by asking how it would be possible for countries to build internal ownership process without communicating among citizens.

A group of parliamentarians from Uganda also noted the lack of communication in the PRSP. They alerted the Bank to the fact that the PRSP process was leaving important citizens out of the loop. This prompted the Bank to broaden the PRSP process to facilitate dialogue with all groups (with a special emphasis on parliamentarians).

|

Participation, the keystone of PRSPs, relies on accurate, consistent and continuous communication that provokes response and encourages debate. Any communication intervention - whether it is a radio program with a phone-in component or a debate with members of the press - should inspire the audience to engage in dialogue. Dialogue invariably leads to better understanding, the application of issues to one's own circumstances and participation in all phases of PRSP. Strategic Communication in PRSP, The World Bank |

Major changes, like global warming or the HIV/AIDs epidemic, are additional factors leading to increased attention on communication.

In summary, the factors that are putting communication on the development map include:

failed or mediocre field implementation experiences;

increased accountability and transparency;

interaction and consultation processes within and among organizations; and

environmental change and epidemics that affect large parts of the globe.

Regardless of the factors that stimulate change, those organizations that are able to embrace change will be doing so by innovating (experimentation, lateral thinking, creativity). It is in these kinds of innovative environments that effective communication is most likely to occur.

Soul City

is a South African health promotion project that harnesses the power of mass media for social change. The doctor who founded Soul City wanted to use mass media to prevent the spread of HIV and promote a healthier lifestyle. Soul City's programs are "edutainment," (education plus entertainment), an enriched version of traditional TV, radio and print. They are popular, designed and produced to air in prime time (rather then in less viewed education time spots), and have become some of the most listened-to programs in South Africa. About two million people watch the show every week. Most of the story lines have focused on HIV/AIDS.

Nine radio stations throughout the country receive the TV manuscript, and rewrite a radio script departing from what was on TV. Once the radio script is done, each station produces its own continuation of the TV story line in its own language.

Soul City uses print media to reinforce the broadcast messages. The booklets are serialized in two languages and published in ten newspapers nationally.

Public relations and advertising have a dual role - to popularize the television and radio shows and to advocate for particular health issues. Soul City is increasingly focusing on media advocacy for healthy public policy, recognizing that communication strategies for meaningful social change cannot focus attention solely on individuals. The numerous structural and environmental barriers in the way of individuals advocating for healthy public policy make Soul City’s advocacy role increasingly important one.

Many evaluations have been integrated into the work of the project. Some include: a national survey with baseline (pre-intervention) and evaluation (post-intervention) measures of 2000 respondents for each survey; a national qualitative impact assessment; an evaluation of the partnership between Soul City and the National Network on Violence Against Women (NNVAW); and a cost-effectiveness study.

Data showed that Soul City contributed to the changing discourse on, and prioritization of domestic violence within National Government. The programs succeeded in putting pressure on government to speed up the implementation of the Domestic Violence Act. The Partnership Evaluation found that the implementation of the Act in 1999 was an achievement largely attributed to the advocacy initiative of the partnership between Soul City and NNVAW and the multimedia component of the Soul City initiative.

Significantly, communities began to shift from silent collusion with domestic violence to active opposition to it. There are anecdotal reports of pot or bottle banging. For example, patrons at a local pub in Thembisa collectively banged bottles upon witnessing a man physically abusing his girlfriend.

Soul City impacted positively on women’s self-worth and sense of identity, in the context of rights-awareness and "new" options. Soul City empowered women to negotiate relationships and (safer) sex. Women interviewed report that Soul City encouraged them to act on this new awareness of their rights in oppressive or abusive contexts, or in contexts traditionally associated with unequal gender power relations.

Source: Gumucio-Dagrón, 2001 and The Communication Initiative [www.comminit.com]

In the Sahel, water is scarce and its management is critical to sustaining rural communities.

However, practices in which poor rural communities are seen as beneficiaries, and where decisions are taken from the outside by government managers or international organizations representatives often lead to non sustainable results and the aggravation of poverty. On the other hand, when communities are actively involved and empowered, and other stakeholders brought to a discussion table with the communities, we can see impressive change. This has been demonstrated while addressing water related conflicts.

An IDRC supported action-research project experimented a Participatory Communication Approach to address water related conflicts with local communities. The research team worked with 19 villages in the Nakanbe River Basin in Burkina Faso. The team and the communities identified three main sources of water related conflicts: the lack or insufficiency of water; deficient management and use of existing water infrastructures; and the lack of communication between end-users.

They also identified causes and types of problems associated with these conflicts. Conflicts between different users (women, little girls, gardeners, merchants, pastoralists, etc.) competing at the water pump were the most common. Ethnic issues also played a role in these conflicts. Members from minority ethnic groups in a community would not have easy use of scarce water resources. Other issues such as ancestral beliefs and taboos, water collection by populations from other villages and the prevalence of diseases related to water were also identified and discussed.

Actions to address these problems fell into three distinct categories. Some of the proposed solutions were of a technical nature. Others aimed at understanding and influencing mentalities, behaviours and taboos. The third category pointed to the organization or restructuration of Water Management Committees.

A consensus-building and decision-making process was then activated and supported by way of a participatory communication strategy. Such a strategy began with the discussion around problems and proposed solutions and flows with the following actions: identifying specific groups in the community and other stakeholders in relation with the problems identified; analyzing communication needs and identifying objectives; developing communication activities and selecting communication tools; implementing, monitoring and evaluating activities and their contribution to the established goal.

In each local community, specific groups of women, young girls, pastoralists, community leaders, members of water management committees and members of different ethnic groups participated in the discussions. Other stakeholders identified outside the communities, such as administrative and political authorities, government managers, development partners and donors were also associated with these discussions.

Activities involved: community meetings, informal group discussions, a roundtable involving all stakeholders (community members, development partners, managers and decision-makers), training of community agents and of water management committee members, theatre, radio transmissions, video projections, organization of forum discussions on the management of water committees, organization of exchange travels between villages, council meetings (Village, Departmental and Regional levels), and elective village assemblies for the election of water management committee members.

These activities supported the process of change at the community level and introduced consultations with decision-makers at the regional and national level that are still ongoing.

As a result, communities’ capacities in organizing themselves to better manage their water, resolving conflict issues and linking with decision-makers were reinforced. Specific outputs included the following: community participation to the rehabilitation of hand-pumps and installations, funds collected in communities and demands addressed to the national water program to assist in the digging of other wells, strengthening of community organizations, improvement of dialogue and collaborative action between different ethnic groups, organizations or restructuring of water management committees, massive involvement of women in these committees, reduction of water-related diseases in the communities, involvement of local, regional and national decision-makers and managers in the search for solutions.

The research emphasised the role of participatory communication in addressing development issues. It also showed the importance of facilitating and reinforcing stakeholder participation in decision-making processes. Finally it also showed that given a dynamic of collective involvement and collaborative action, people can fight poverty and find solutions to their problems.

This project was supported by

the

International Development

Research Centre and by

a team of

CEDRES, University of Ouagadougou,

0-led by Nlombi

Kibi.

|

[4] Wheatley, M.J., 1992.

Leadership and the new science: Learning about organizations for an orderly

universe. Berret-Koehler: San Francisco, p. 113. [5] Fraser, 1996. |