Under the CDMP support project of “Improved Adaptive Capacity to Climate Change for Sustainable Livelihood in the Agriculture Sector” of FAO and DAE, the CEGIS has carried out this analytical study titled: “Study on livelihood systems assessment, vulnerable groups profiling and livelihood adaptation to climate hazard and long term climate change in drought prone areas of NW Bangladesh”. The study objectives, conclusions of the study and recommendations derived from the study are outlined in section follows.

Study objectives

The major objectives of the study was fivefold: a) assess local perceptions of climate hazard, past and present climate risk/ impact; b) study livelihood systems and establish livelihood profiles of the major vulnerable groups; c) investigate about current and past (30 years) adaptive responses and coping strategies of the vulnerable groups to risks in particular climate risk; d) institutional assessment; and e) develop a description of the physio-geographic environment and framework conditions of the study areas.

The study was carried out in four pilot upazilas of two districts - Chapai Nawabganj and Naogaon - of the northern Bangladesh. The pilot upazilas were: Porsha, Sapahar, Nachole and Gomostapur.

Synoptic of the findings

The present study found that both the climatic conditions and the anthropogenic factors are contributing towards the vulnerability of the life and livelihoods of the people. Climatic factors are creating the vulnerabilities but due to the anthropogenic capabilities (and the access to various forms of assets) livelihoods are becoming more vulnerable and leading towards disasters and losses. This is a dual effect of climatic and anthropogenic at the same time.

| |

| Climate variability (e.g. erratic rainfall.) | Non-climatic factors (e.g. availability of electricity). |

Local perceptions

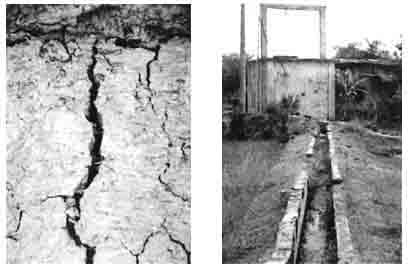

The study found that the people hold various perceptions towards the current and past risks in the study area. People perceive that the current climate in the area has been behaving differently from the past years. The seasonal cycle (locally called rhituchakar) has changed, droughts became more frequent, pest and disease incidences increased, average temperature has increased in the summer while winter has shortened and the severity of some winter days increase. However, people found difficulties in expressing the degree of changes. Local people in the study area have also perceived that their boro, aus and winter vegetable production, fruits (several varieties of mangoes) remained affected due to temporal variations in rainfall, temperature and variability in drought occurrences.

Livelihood profiles

Adopting an innovating analytical Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) the study profiles the major livelihood groups in the area. It was observed that the livelihoods are severely affected by drought situation. The access to boro, aus and rabi remains largely dependent over the access and availability of the irrigation water. Failure in getting access to DTW water in the non-irrigated areas and the occurrence of several anthropogenic factors (e.g. electricity failure, high price of agricultural input) remains as the major form of vulnerability for the farmers. The wage labourers face unemployment and crises of failed migration. Petty traders find difficulties in getting buyers on a regular basis. In this thriving situation, the large businessmen and large (or rich) farmers were found vulnerable by a lesser degree. However, these groups are found vulnerable to the climatic hazards in a covariant (all in analogous condition) way but having access to the higher degree of assets other than the natural (mostly financial, social and physical) the group actually keep them out of severe vulnerabilities caused by climatic conditions.

Local adaptive practices

In this difficult climatic conditions, the study identified that there are some local adaptive practices existing in the study area. Four major types of adaptive practices: a) traditional responses (e.g. pond and dighi excavation, retention of rainwater in khari and canals, shedding, tillage, breaking top soil), b) state supported responses (e.g. DTW facilitated irrigation), c) alternative responses (e.g. adoption of mango farming, orchard developing), and d) some domestic responses (e.g. alternative livestock and poultry/birds rearing) are existing in the study area. The study found that the successes derive from these adaptive practices are of relative nature: some are promising, some brings a limited success and some have only a low efficacy in severe conditions of severe drought or in variable climatic conditions.

Institutional domain

The study looked into the institutional domain under which these groups are trying to survive in. Several types of institutions: government and local government agencies, NGOs, social, informal and private institutions; and farmers/water user groups were found to be operating in the area. The institutional assessment found that the agencies operating in the study area have differences both in roles, capacities and how-hows to deal with climatic risks. At the moment with their mandates in providing DTW irrigation BMDA is providing some support in their operated areas but is offering only a little to the areas where the ground water is not accessible. The local level structure of union disaster management committee for disaster management was also found officially there but it emerged from the discussion with the local people that the access to these UDMCs and capacity of these institutional entity is very week. The involvement of NGOs in local disaster risk management is not quite deeper consider to any other disaster prone areas of the country. Lack of coordination among the NGOs and NGOs and with government remained as a critical institutional weakness as well.

At this point on the basis of the study findings the following issues could be recommended:

The risks persisting in the study area is of a dual nature. The climatic and anthropogenic. The former is a direct physical factor and featuring variability and the later is caused by the idiosyncratic characterization of the farmer community as well as covariant nature of state support. However, in this situation the further understandings and actions for adaptation need improvement at both levels. The study recommends multiple pathways to improve adaptive responses that would comprise of both long-term and short-term adaptive measures. Such multiple pathways could comprise of:

the treatment of the climatic risks through physical4 adaptive measures if possible (e.g. planned physical water resources management),

the adaptation to climate change through improved non-structural disaster risk prevention and preparedness activities;

the adjustment/alteration of agricultural practices (e.g. setting up adequate cropping pattern and selection of tolerant crops); and

the creation of alternative livelihoods opportunities for future other than traditional crops.

Setting up of a planned adaptive strategy for long and short term adjustments to the climate change and climate variability is a requirement. An optimal and flexible combination of the adaptation options available with respect to the climatic and non-climatic domains needs to be developed for respective geo-physical context and livelihoods. This combination and balance might comprise of a combination of adaptive options of:

physical adaptive measures (e.g. link canals, storage facilities for retaining water);

adjustment of agricultural practices (e.g. adjustment of the cropping pattern and selection of right varieties of crops);

enhancement and adjustment of irrigation procedures and systems (e.g. irrigation scheduling, canal improvements);

shift and switch to alternative crop (e.g. selective adoption of mango as cash crop),

socio-economic adjustments (e.g. migration, market facilitation);

risk reduction measures (e.g. facilitation of the existing mechanisms to reduce distressed conditions such as facilitated/planned migration),

situating enabling institutional environment and policy formulation for enhancement of adaptive livelihood opportunities;

awareness and advocacy on climate change and adaptation issues;

strengthening of community resilience including local institutions and self help capacities;

research and innovation of adequate/improved crops (e.g. drought tolerant and low irrigation varieties/crops selection), and other conducive and adaptive factors.

Figure 9-1. Combination of few possible adaptive options

Among these above adaptive options/possibilities, some initiatives would remain as the climate change only measures, some options would remain climate change and development questions and some options would remain as the development only measures. The challenge would be to find out the right combination and integrating among these varied adaptation options that would be required for respective “geo-physical settings” and “livelihoods systems”.

Setting and selecting these livelihood options are about stretching the limits of the local adaptive responses as well as the innovation, experiences, technologies appropriate to the livelihoodsculture and environment of the respective areas. In this respect, these adaptation options could comprise of climate change specific adaptation options but also build on with the mainstream development endeavors (for a schematic presentation see the Figure 9-1).

The study identified that although the climatic conditions have a covariant impacts or effects over agriculturally based livelihoods in the area. But the impacts are of varied in nature for the major vulnerable livelihoods groups in the area. These relative differences are often associated with the idiosyncratic natures or characteristics of the livelihood groups themselves. In devising and considering adaptation options these adaptation options needs to keep open for respective livelihood groups. One good example is the need of water for fishers and for farmers. Fishers need water to be retained for culture fisheries where as the farmers need water for irrigation. Adaptation options needs to be kept open for both kind of situations and with a more solution oriented mindset for future changed conditions.

At this point considering the adaptive responsibilities awareness activities considering futuristic adaptive sensitivity should be devised. The awareness of both the layers the community level people’s awareness raising activities as well as capacity building activities of the grass-root and operational level managers of respective sectors needs to carried out for a growing a habit of adaptation at a functional level.

A major recommendation of the study, however, is that the further awareness and advocacy activity is needed. It should comprise of both the technical understanding of the probabilistic climate change/variability with a combination of deep consideration of the local practices and local idiosyncratic factors that are deep rooted into the cultural characteristics of the community itself. This could be recommended that an enhancement of the awareness activities need to be developed interpreting the technicalities of the climate science into a locally understandable (and interpretable) format. This could be considered as a pivotal aspect of a sustainable awareness rising for future adaptation and internalizing the process at community level.

The institutional assessment in the study area suggested that the official presence of the line agencies at upazila level is there in all study upazilas. Some of the departments such as the BMDA and DAE seems to have a more local level presence. However, one striking aspect as identified by the common livelihood group members at community level is that the functioning of the disaster management at the lowest tier which is the “Union Disaster Management Committees (UDMC)” at union level seems quite poor. These UDMCs taking the line agency representations from the respective departments (i.e. DAE, Department of Livestock, Department of Fisheries) needs to be considered for capacity building and for creating further awareness on climate change/variability issues and their possible adaptation measures. In this respect this would be strongly recommended that the UDMC’s (with the facilitation from DAE and other components of DMB) could play the central role at community level.

Vulnerable group members have a very superficial idea about these union level disaster management committees where the participation is quite low. However, a central findings of the study is that the local people are aware of some of changes and variability of the climatic nature but people are not quite institutionally adequately formed together for making their points in an organized manner for possible alternatives and seeking further options. In this respect, awareness programme along with motivational activities to grow greater participation need to be enhanced among the vulnerable groups. In order to ensure participation of vulnerable groups in a more democratic or innovative way from all sections of the vulnerable groups needs to be considered. If needed then special by-laws or policy formulations can also be devised for special situation.

Another very central element that derives from the study is that the development of the livelihoods adaptation options needs to focus on following major aspects of:

Developing “micro-meso-macro” linkages:

The horizontal and vertical linkages need to be established for situating an enabling environment for adaptive strategies. The linkages at community between the line agencies working at upazila and union level needs to be more synchronized and more focused on the climate change adaptation issues. At present, in the study are many of the organizations are seemingly operating in isolated domains and have limited concerted efforts. This needs to be enhanced.

In addition to this the vertical linkages with the agencies (govt. departments and NGOs), business bodies, markets, labour groups, agricultural machinery businessmen and farmers needs to be strengthened.

The information flow, sharing of ideas, sharing of technologies, planning systems are also needed to focus more micro to meso and macro dimensions and vise-versa.

Linkages to the BD-NAPA process and follow up to the national adaptation initiatives:

For adaptive purposes against the climatic variation and changes the national level initiative of Bangladesh NAPA has already been in formulated. At present, under the Ministry of Environment has developed the BDNAPA with the active participation from various ministries and stakeholders in regions. However, one of the major recommendations of the present study could be: the community level realization/findings through the present contribution from agriculture sector can develop an “interface of linkage” with the community level. While the national NAPA provided a regional and national sectoral outlook the present contribution from the agriculture sector in the form of present study could contribute to the mainstreaming of adaptation activities that the BDNAPA has initiative. Strength can be gained from present study and the actual realistic community level practices and perceptions can be incorporated and liked with the national and regional activities in a smooth manner. This would be an added feature to the development of national sustainable environmental governances in a more practical manner.

In this process the local level adaptive issues can be linked with national and regional regulatory, institutional and policy issues. This would be highly beneficial for the improvement of local level adaptation relating to issues such as irrigation enhancement, increased facilitation for surface water, negotiations of river links and so forth. Linkages with the developments of the national research bodies (such as rice and fruit research), programmes, national climate change-adaptation research, linkages with electrification/energy policy, environmental governance and other forms would be useful.

The study strongly recommends that both types: long-term and short-term measures for adaptation would be needed in future. The study found that the present adaptive responses are of relative success: some are promising, some brings a limited success and some have only a low efficacy in severe conditions of severe drought or in variable climatic conditions.

In this respect, along with the above stated recommendations as of immediate action the awareness raising and experience sharing for livelihoods adaptation to climate change are essential. And for future long-term adaptation innovation, technologies appropriateness and alternative adaptation measures need to study further.

But, for both the contexts: a) linkages between climate change adaptation and the mainstream development needs to be established, b) development of an enabling institutional environment is required for climate change adaptation where the institutional coordination and collaboration between right kind of institutions, policy formulation, planning and introducing policies conducive to climate change adaptation are required.