|

The implications of the Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture for developing countries |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Chapter 2: The main elements of the Agreement on Agriculture |

||||

|

What this chapter is about

This Chapter provides a brief overview of the main elements of the Agreement on Agriculture. It outlines, under the headings of Market Access, Domestic Support and Export Competition, the principle policy mechanisms which the Agreement is concerned to limit, and the main elements of the Agreement which are designed, in association with the presentation of Country Schedules, to achieve these objectives. A more detailed analysis of these elements, and how they concern developing countries in particular, is left to Chapter 3, which examines practical implementation issues, and looks at how the text of the Agreement can be interpreted.

Aims of this chapter

What you will learn

2.1 The objectives of the Agreement on Agriculture

The primary objective of the Agreement is to reform the principles of, and disciplines on, agricultural policy as well as to reduce the distortions in agricultural trade caused by agricultural protectionism and domestic support. These forces have become very strong in recent decades, as developed countries, in particular, have sought means of protecting their agricultural sectors from the implications of unfettered markets.

The purpose of the Agreement, then, is to curb the policies that have, on a global level, created distortion in agricultural production and trade. These policies can be divided into the following three categories: market access restrictions, domestic support and export subsidies. Each of these categories of policy making are dealt with in turn by different Articles and Annexes within the Agreement, and are referred to in the text as:

Before looking more closely at the Agreement's interpretations of the three main policy areas, it is worth taking a broader look at these policies, and at the rationale for subjecting them to GATT disciplines.

2.1.1 Market access restrictions: Protecting producers from international competition

The deployment of market price support policies can involve considerable cost, both to the taxpayer and to consumers, as in Europe and Japan, for example, where the agricultural support policies place a particularly heavy burden on the consumer.

Restrictions on market access typically take the form of:

The latter include, for example, complicated, time-consuming bureaucracy and restrictive licensing procedures, all of which can serve as an effective impediment to trade. Some non-tariff-barriers (NTBs), such as import quotas and variable levies, are particularly distortionary, in that they isolate domestic producers from the effects of world prices and therefore magnify instability on international market.

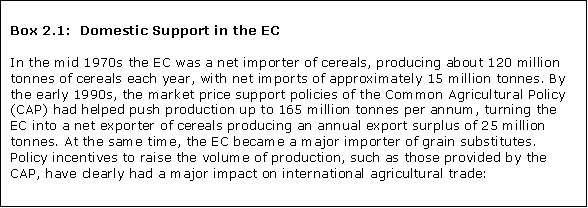

2.1.2 Domestic support policies: Their effect on production and trade

Domestic support policies include a variety of measures aimed at raising the income of producers and sustaining the profitability of domestic farming.

The following policies frequently do have a distortionary effect.

On their own, border controls are only likely to be effective in providing market price support if the country is a net importer, of more than marginal quantities, of the commodity in question. In the case of an export tax, of course, governments intervene at the border in order to acquire tax revenue. If the commodity is also consumed domestically, this could depress the domestic price by reducing the volume of exports.

Agricultural policy is usually characterised by a combination of both government intervention of the type described and border controls, since to use either of these interventions in isolation would be likely to lead to a leakage of support to those for whom it was not intended.

It is important to remember that discussion of market price support in the Agreement, refers only to support prices that are administratively set by government; it does not include price support that is achieved through import barriers alone.

As with market price support, these payments ensure that the producer's revenue per unit of production is higher than would be the case without government intervention. For, a given administered price, this form of support places less of a burden on domestic consumers.

2.1.3 Export Subsidies: Disposing of Surpluses on the World Market

As has already been suggested, policies that provide substantial support to domestic producers frequently result in the production of large domestic surpluses. For example, in many developed countries where the response in demand as a result of price and income changes is small, i.e. demand is price or income inelastic, the volume of a commodity produced by domestic farmers in response to price support, quickly outweighs the volume purchased by domestic consumers. The problem then is how to dispose of such surpluses.

Such export subsidies have been typical of the path chosen by governments in their efforts to dispose of domestic surpluses. It is these subsidies that have facilitated the sale of large EC and US surpluses on the world market, causing the international prices of many agricultural commodities to be depressed and accentuating world price instability.

2.2 The main elements of the Agreement

2.2.1 The country schedules

Most focus and interest obviously falls on the three categories of policy making outlined, especially since these are addressed explicitly by different sections in the text of the Agreement. However, it should be remembered that the Agreement was not the only legal document to come out of the Uruguay Round negotiations on agriculture. Although, the Agreement lays out the basic rules and definitions regarding policy making, it does not include within it specific quantitative commitments on a country by country and commodity by commodity basis.

The country schedules comprise a statement by each member government, on a commodity by commodity basis, of their position on each of the issues concerned (tariffs and NTBs, domestic support and export subsidies) prior to the implementation of the provisions of the Agreement, together with an outline of how the provisions will be achieved. The rules governing how the Country Schedules should be created were laid out in a document entitled the Modalities for the Establishment of Specific Binding Commitments Under the Reform Programme, generally referred to as the Modalities.

Having presented the Country Schedules, a period of time was demarcated during which any member could question and seek to change the content of any other member's schedules. This period was described as the verification process. The period that commenced in December 1993, following the adoption of the Uruguay Round Agreement, and ended in April 1994, shortly before the Marrakech Ministerial Meeting, was allotted to this process, i.e. for countries to have the opportunity to examine, and negotiate amendments to, each others' proposed Schedules. However, it would seem that only very few such amendments were actually made to the Schedules during this time.

The Country Schedules are an essential part of the Agreement, and the text makes frequent reference to the commitments made within them: for example to reduce tariffs on particular commodities by a given amount over the required time period. Once the commitments have been made, there is a legal obligation on the part of member governments to implement them.

We will now consider the main elements of the three categories of policy described above, in terms of the technical requirements placed on governments. A more detailed appraisal of the policy implications of these provisions is left to the following chapter.

2.2.2 Market access

The provisions and commitments defined by the Agreement and the Country Schedules with regard to Market Access include a number of important elements. These can be roughly divided into the following four areas:

Tariff reduction.

Market access provisions, that oblige countries to provide "low" import tariffs for a fixed quota of imports.

Special treatment and special safeguard provisions, that provide exemptions from the above commitments.

Tariffication and tariff reduction

Tariffication, or the replacement of NTBs by tariffs, is an important part of agriculture's inclusion within the framework of the GATT, in that it brings agricultural trade policy into line with the GATT principle of transparency, and potentially eliminates some of the distortionary effects that NTBs have on trade. The Agreement has the following provisions:

In cases where there were no NTBs at the start of the Uruguay Round, the value of the baseline tariff was taken to be either the customs duty that was prevailing at the beginning of September 1986 (the start of the Uruguay Round), or where this was lower than an existing tariff binding/commitment, the value of the latter.

For developing countries the commitments are 24 percent and 10 percent respectively, and the implementation period extends to ten years.

For least-developed countries there are no reduction commitments.

Market access commitments

Market access provisions are an important element of the Agreement. These are designed to encourage the development of trade, and to ensure existing export markets are maintained. Thus, where there is little existing trade (taking the base period average as the benchmark), or where existing levels of imports are not maintained, importing countries are required to allow stipulated quantities of imports at a reduced rate of tariff. Thus, the market access provisions allow for the following:

These market access provisions do not apply when the commodity in question is a traditional staple of a developing country. Provided that certain conditions are met, a different set of provisions apply which give governments greater flexibility with regard to what are described as sensitive commodities. These arrangements are discussed in the next chapter. Also reviewed are the mechanisms for providing the opportunity for market access, particularly the implementation of import quotas at reduced tariff levels.

2.2.3 Domestic support commitments

As suggested in Chapter 1, in order to limit the trade distortions caused by domestic agricultural support policies the Agreement introduces commitments intended to curb these policies. These commitments on domestic support are aimed largely at developed countries, where levels of domestic agricultural support have risen to extremely high levels in recent decades. This constraint on policy design is to be achieved by:

For developing countries, where agricultural support policies are deemed to be an essential part of a country's overall development, the obligations are generally less demanding.

The aggregate measure of support

This concept is a measure that quantifies, in monetary terms, certain aspects of the support provided by agricultural policies. The AMS calculation includes all domestic support policies that are considered to have a significant effect on the volume of production, both at the product level, and at the level of the agricultural sector as a whole. Market price support, except that which is achieved through border controls alone, is a major component of the AMS calculation.

The AMS is calculated by first deriving the levels of support for each commodity, plus a similar calculation for non commodity-specific support. Each of these is then summed to provide the aggregate measure. Apart from those polices which are included in the calculation, there are a large number which are excluded. Whether or not these have, in reality, a significant effect on production is, in some cases open to interpretation. Policies are categorised as follows:

The 'green box'

'Green box' policies include a variety of direct payment schemes, that subsidise farmers incomes in a manner that is deemed not to influence production decisions. They also include assistance provided through:

From the point of view of developing countries exemptions relating to food security, domestic food aid and the environment are of particular interest.

The 'blue box'

Most of the exemptions to AMS commitments are policies placed in the 'green box'. Some additional polices also gain exemption, however, as a result of the accord reached at Blair House. These are the so-called 'blue-box' polices. The most notable of these are the compensatory payments and land set-aside programme of the EU's Common Agricultural Policy, and the United States' deficiency payments scheme. Such direct payments under production-limiting programmes are exempted from AMS reduction if:

'De minimis' exemptions

As noted above, AMS calculations are carried out for each commodity and for no-specific support. The 'de minimis' exemption allows any support for a particular commodity (or non-specific support) to be excluded from the total AMS calculation if that support is not greater than a given threshold level. Thus, an additional exemption is contained in the provisions of the Agreement, in the following circumstances:

For evaluating the level of support that is provided to the agricultural sector, the Agreement refers to four different measures of support. These can be summarised as:

The domestic support commitments are defined in the Modalities as requiring a 20 percent (13.3 percent for developing countries) reduction in the Base Total AMS, to take place in equal annual instalments over the implementation period.

The resulting domestic support reduction commitments are included in the Country Schedules. To ensure that annual reduction commitments are being complied with, Current Total AMS values are established in each year of the implementation period.

2.2.4 Export Subsidy Commitments

As we discussed in the opening chapter, the subsidised export of agricultural surpluses has been a major source of international trade disputes, and the distortions that it has created on world markets, in terms of price and general market instability have been substantial. It is partly for this reason that the Agreement reached on export subsidies is seen by many to be the most important element of the Agreement, and likely to have the most immediate and direct impact on world markets.

Although agriculture does still receive special treatment in the area of export subsidies, in that, unlike in the trade of other commodities, export subsidies are still permitted, the Agreement did introduce constraints on such policies, where previously there were none. The essence of the Agreement with regard to export subsidies is as follows:

Reduction commitments

The schedule for implementing cuts appear in the Country Schedules. These specify:

These commitments are given for both the value of subsidy expenditures, (expressed in US$) and in the volume of subsidised exports (in tons).

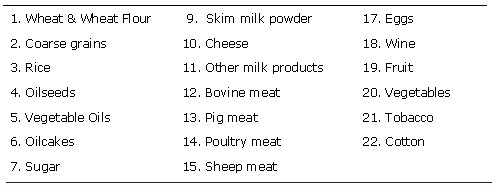

Table 2.1: Commodity grouping for export-subsidy commitments

The base period

The base period for the purpose of the export subsidy commitments is different from the 1986-88 base period relating to commitments on market access and domestic support.

However, an exception to this was negotiated between the US and the EC, under what was called the "front loading" accord, which was reached in December 1993, just before the conclusion of the Round. This allowed that:

This was permitted provided that by the end of the six year implementation period, the cuts still brought subsidies down to the level that would prevail had the base period level been used as a starting point.

The Agreement came about because in some cases export subsidies had continued to increase substantially following the 1986-90 base period, and it was felt that a sudden cut to the base period level would have been too demanding. The result was that while the overall cut in export subsidies, under these arrangements, will have to be larger, the impact of the reduction at the beginning of the implementation period is minimised.

|

||||