|

What this chapter is about

This chapter focuses on the policy responses and implications that stem from the Agreement on Agriculture. The focus is upon the manner and extent to which policy design is constrained, or otherwise influenced, by the commitments undertaken in the Agreement. Central to this is the influence the Agreement will have on production policy in developing countries and government concerns to promote both internal food security and external market opportunities via agricultural exports.

For most developing countries, the implications of the commitments undertaken in the Agreement need to be examined within the framework of policy initiatives currently taking place. The trend in recent years has been towards market-oriented economic reforms and unilateral trade liberalisation. In Africa, in particular, these reform packages have been introduced under the guise of structural adjustment programmes with emphasis on internal and domestic liberalisation. Clearly there is an intuitive rationale in assuming that the two, internal reforms and external liberalisation commitments, are compatible.

It is difficult to make broad generalisations as each developing country is faced with particular constraints and objectives in the formation of macro-economic and agricultural policies. However, in this Chapter we seek to elucidate some of the broad trends in policy formation in developing countries, and investigate the implications the Agreement will have on internal policies with respect to compliance with both the Agreement and reform programmes.

Aims of this chapter

- To highlight the implications of the Agreement for Agricultural Policy in Developing Countries.

- To examine the implications of the Agreement in the context of policy constraints presented by domestic reform programmes.

What you will learn

- About domestic policy considerations in the light of both the Agreement and structural adjustment/economic reform programmes.

- An understanding of both internal and external opportunities and constraints in agricultural policy design.

5.1 The policy environment

5.1.1 Domestic policy and the Agreement commitments

The economy-wide impact of reforms to domestic policy is likely to be insignificant in the short term, because of the combination of 'green box' policies available and the special and differential conditions.

As we showed in chapters 2 and 3, the 'green box' policies in conjunction with the special and different treatment given to developing countries provides a degree of flexibility for developing countries with regard to policy design. Recall that the essence of the 'green box' measures is that they must be Government funded and entail neither transfers from consumers to producer (particularly those via manipulation of the price structure) nor direct price support. The basic aim of the exemptions is to avoid distortions that encourage overproduction and hence distort comparative advantage.

Conditions attached in the 'Green Box' include:

- General services: including research; pest control; training and extension;

- Public stockholding for food security purposes, provided that any buying and selling associated is carried out at market prices;

- Food aid provided that the financing is transparent;

- Direct payments to producers, e.g. de-coupled income support; income insurance; retirement schemes; investment aids for restructuring;

- Payments under environmental programmes;

- Payments under regional assistance programmes.

Under the Special and Differential conditions accorded to developing countries the following types of support are exempt:

- Investment subsidies which are generally available to agriculture;

- Input subsidies to low income or resource poor producers in developing countries;

- Subsidies to reduce the export marketing costs for agricultural products;

- Internal, and international, transport subsidies for agricultural exports.

5.1.2 Economic reform programmes and the structural adjustment framework

Since the mid-eighties many developing countries have embarked upon economic reform programmes that have aimed at internal and external liberalisation. These market oriented reforms have been high on the agenda of developing countries prior to the completion of the Uruguay Round of Negotiations. It is true to say that these countries have maintained, and in some cases speeded up, the pace of economic liberalisation during the Uruguay Round Negotiations, notably the countries of Latin America and south-east Asia.

The trend towards greater liberalisation in domestic policies has been due to both internal and external forces. In the countries of Sub-Saharan Africa many countries are undergoing Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) which have involved substantial liberalisation measures accompanied by fiscal and monetary austerity and devaluation. Whilst in Latin America and South Asia structural adjustment loans have been accompanied by similar economic reforms initiated by governments in conjunction with a move towards greater openness in multilateral trade. Thus, the trade liberalisation resulting from the Uruguay Round can be seen to complement the implementation of these reform programmes.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, since the 1980's, the policy environment has been characterised by constraints and disciplines imposed by a structural adjustment framework which has been externally driven. Loans from the World Bank and the IMF are made conditional on the implementation of substantive economic reform programmes. Countries undergoing these programmes and in receipt of these loan packages are highlighted in table 5.1.

The stabilisation component of SAPs usually involves the devaluation of the national currency (the overvaluation of exchange rate has been a common underlying cause of non-competitiveness and domestic price distortions) in relation to the major traded currencies, and government expenditure reductions. The aim is to transfer resources from the production of non-tradable to tradable goods. Thus, the greater openness encouraged via the conclusion of the Uruguay Round negotiations reinforce this trend.

Economic reforms have encouraged a movement of policy initiatives away from taxing agriculture to supporting it as the source of economic growth and foreign exchange earnings. This places great emphasis on agricultural commodity producers who have experienced a dual effect of reforms, namely higher producer returns and higher costs of imported inputs. The pressure to increase production is reinforced by both rising populations and high food import bills stemming from the devaluation.

- Thus, as a result of the reform programmes, the agricultural sector has moved gradually away from a position where it was subject to indirect taxation via an overvalued exchange rate, and a recipient of low levels of investment in rural infrastructure.

The need for policy support in the short to medium term provides the rationale behind the concessions in the special and differential treatment provided in the Agreement. The issue is the provision of support in the face of fiscal constraints imposed by the structural adjustment programme itself. As a consequence, appropriate targeting of policy is crucial since expenditures need to be directed towards

- producers and regions in most need of support;

- areas where the resources will be most efficiently used.

We examine the policies to achieve this in the next section, while also looking at the extent to which the commitments undertaken in the Agreement place constraints on them.

Table 5.1: Developing countries in receipt of SAF/ESAF and/or SAL/SECAL Loansa

a The years refer to the dates of approval of each country's first SAF/ESAF and SAL/SECAL.

Source: UNCTAD, The Least Developed Countries, 1993-1994 Report.

5.2 Agricultural production policy tools after the Agreement

5.2.1 The domestic policy options

In this section we will examine the impact the Agreement will have on some of the policy instruments currently used in developing countries and whether they comply with the disciplines it imposes. Box 5.1 highlights the total support allowed to agricultural producers compliant with the Agreement.

Source: Konandreas and Greenfield, 1996

In relation to the commitments/constraints imposed some special points should be noted or reiterated:

- It is important to understand that at no point does the Agreement ban any specific production policy, either for developing or developed countries, even for those policies that have trade distorting effects.

5.2.2 AMS issues

The agreement that the current total AMS must not exceed the base total AMS which, where positive, must be reduced by 13.3% over 10 years by developing countries. It might appear that this does not provide developing countries with too severe a commitment. However, there are problems which may arise as a result of a zero or low base AMS.

This point can be illustrated, if we consider the commitment undertaken concerning government purchases for food security purposes.

- Food security purchases must be undertaken at prevailing market prices. In addition, provision for developing countries allows for purchases at administered prices as long as the difference between the purchase price and the external reference price is included in the AMS of the country. The value of this concession is effectively negated by the zero or negligible AMS submitted by the majority of developing countries, since its inclusion would lead to a non-compliant rise in the AMS.

In certain cases, this problem can be overcome through use of the de minimis clause which would allow procurement at administered prices.

5.2.3 The de minimis implications

As explained above, the de minimis provision is extremely important in view of the lack of flexibility which may be implied by the AMS provisions. The 10% de minimis commitment for developing countries means that as long as price support is less than 10% of the value of production, then the policy will comply with the agreement.

The importance of this is sizeable if one considers that price support is given to the value of marketed output rather than total value. As suggested in Chapter 3, the lower contribution of marketed production in relation to total production creates the situation where the lower the marketed share of output the higher the price support that can be provided. Thus, if marketed output is 25%, then the 10% de minimis could be equivalent to a 40% price support on marketed output.

5.2.4 The implications for specific policy instruments

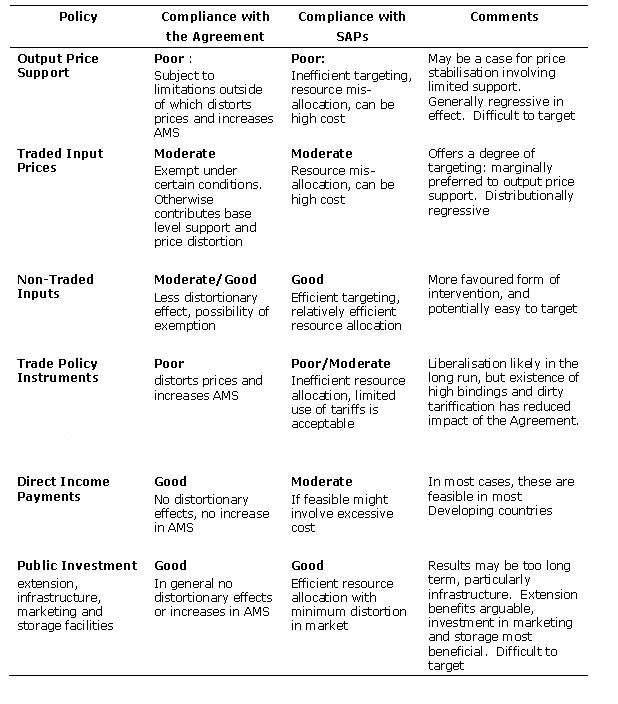

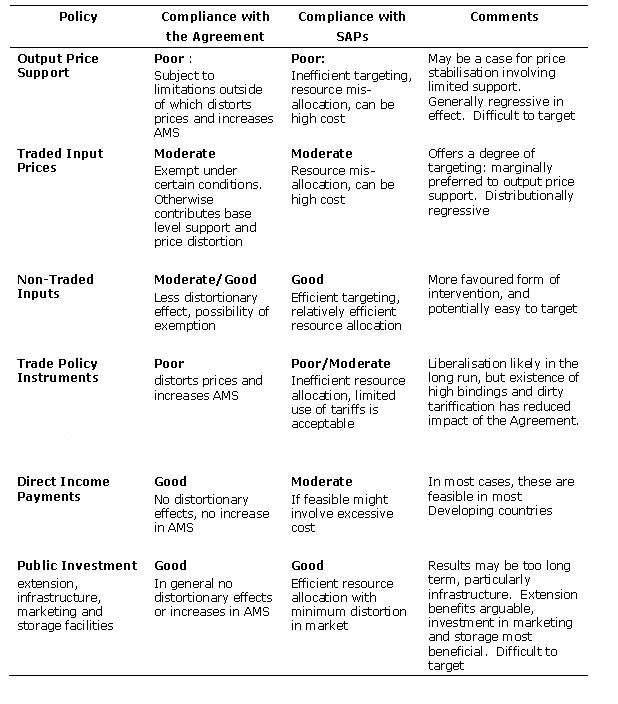

Table 5.2 provides an overview of the implications for specific policy instruments in the context of the Agreement and domestic reform programmes as embodied by economic reform programmes. We examine the implications for each instrument outlined in Table 5.2 in more detail below:

Table 5.2 The policy options under the Agreement and SAPs: A conceptual framework

- Output Prices: Commodity specific mechanisms using some form of administered price to support producer prices.

This has been the most common form of government intervention and protection used in the agricultural sector in developing countries. Domestic intervention to influence output prices involves the commitment of scarce public resources and/or further protection of domestic production via tariffs or, prior to the Agreement, other restrictions on imports.

The manipulation of the price system is a blunt instrument in that it is unable to target its impact and fulfil its objective of raising or ensuring an adequate income on an equitable basis. It is also likely to be regressive in its nature since the producers will benefit according to the quantity of produce marketed.

Greater effectiveness can be achieved if intervention stabilises domestic prices at the border price, using the range determined by the import and export parity prices. Provided that a long enough time period is used and account of the limitations of import-export parity prices is made, such a policy may not distort prices unduly.

- The key issue with regard to the use of this form of intervention is the effect on the AMS. As noted in earlier chapters, however, the de minimis provisions and Special and Differential conditions provide a degree of flexibility.

- Traded input prices: Actions influencing the prices of seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, machinery etc. Typical forms of intervention are subsidies for chemical inputs and fertilisers, either on a sectoral basis, or targeted towards particular groups of farmers or commodities. The distribution of these inputs has usually involved public sector activity since private sector efforts usually mean remote areas not receiving access because of poor rural infrastructure.

The advantages of input over output price support include:

- the ability to promote the use of certain techniques or patterns of production;

- lowering the perceived risks involved in using a new technique or input;

- greater impact on production per unit cost relative to output subsidies;

- they are more straightforward to use, since they can be enacted at source, and may not necessarily involve the maintenance of physical capital to purchase and sell commodities.

In relation to the Agreement, when they are targeted towards the poor they are exempt. Thus, input commodity intervention may substitute for output price intervention. But the critical issue for Policy-makers is how to target the subsidies effectively to those most in need.

There are some disadvantages:

- support does not guarantee the use for a particular commodity;

- subsidisation of one input can distort factor prices and lead to inefficient combinations;

- may be non-compliant with respect to structural adjustment;

- excessive or inappropriate fertiliser use resulting from subsidies can contribute to environmental problems.

Overall, like output price intervention, input price intervention can have a regressive impact as the better off farmers are usually the ones to benefit most in the absence of effective targeting.

- Non-Traded input prices: primarily credit subsidies; also implicit subsidies/taxes on water electricity etc. Such subsidies are generally compliant with the Agreement, since it are not considered to be trade distorting.

Interest rate subsidies, have certain advantages: they are less difficult to target and less likely to lead to inefficient resource allocation or price distortions. As such, they promote efficient use of resources and are compatible with both structural adjustment programmes and the Agreement. Moreover, credit subsidies need not directly affect commodity prices or quantities.

- Marketing Interventions: activities which influence the functions of marketing intermediaries and the financing of marketing costs. Marketing subsidies are often considered as a concomitant of output price manipulation. Typically, the marketing subsidies have been linked to commodity price policy in so far as the supported price or price range cannot be maintained without public subsidy of the marketing agency or parastatal. Support to import substitutes contribute directly to the AMS and would therefore be influenced by the 10% de minimis commitment in the Agreement.

However, this is not the case for exports where subsides to reduce the marketing costs and to reduce domestic and international transport costs are exempt from contributing to the AMS.

- Non-price Measures: direct ('decoupled') income payments; income insurance; restructuring grants. In general, these are policies more commonly used and applicable in developed countries where the problem is 'over' and not 'under' production.

Other 'green box' measures, include public investment in the form of extension services, infrastructural development or the provision of marketing and storage services.

==> Such public expenditures have been squeezed at a time when they are most needed in order to support agricultural development, as a result of the fiscal austerity imposed via structural adjustment programmes. In addition, agricultural development requires the provision of services which the dismantling of state enterprises has impeded.

Thus, there are specific agricultural production policies that can reinforce macroeconomic and trade policy reforms, but careful consideration needs to be given with respect to the setting of the levels of intervention. The following extract highlights the policy issues faced by developing countries in the context of internal and external policy influences:

Domestic market reform involves sending appropriate price signals to producers as to what goods are needed and wanted by consumers (both home and abroad) and allowing producers access to productive inputs and capital for investment. This usually means relaxing government restrictions, in particular those that keep prices down, and often involves more private sector (competitive marketing). It may also require the development of suitable policies to target assistance to the poor (both as producers and consumers). In addition, stabilisation programmes can usefully protect domestic industries from the vagaries of short term world market price fluctuations. Such stabilisation policies should not, however, mask the longer term trend of prices on world markets.

FAO 1993a, page 40.

5.2.5 Consumption policy options

The provision of affordable food is a key component of the food security policies pursued by developing countries. The implications of the Agreement for consumption support programmes, either via general food subsidies or ones targeted towards the poorest groups in society, is an important issue.

The relevant provision in the Agreement is under 'food aid' in the 'Green Box'. In general, the basis for food assistance is based on nutritional criteria. The additional and more relevant provision for developing countries allows for subsidised food prices that aim to provide the poorest sections in urban and rural areas with food at reasonable prices.

- the real constraints on government food security programmes will come not from any constraints imposed by the Agreement but rather budgetary constraints that may come from economic reform programmes which cause cuts in consumer support programmes.

Food security issues are addressed by the Decision on Measures Concerning the Possible Negative Effects of the Reform Programme on Least Developed and Net Food Importing Countries. The essence of this decision allows for increased food aid and other measures of support which will allow the effects of any consumer price increases to be dampened while allowing producer prices to rise for farmers. The issues surrounding this Decision are addressed in greater detail in Chapter 7.

5.2.6 Domestic market stability

In the previous chapter we argued that there would be likely price changes as a result of the liberalisation process initiated by the Agreement commitments. The important issue for the domestic policy concern how to absorb any external shocks resulting from greater openness to the international domestic agricultural markets.

Four likely trends or impacts on market stability can be highlighted which will require policy responses and changes. These are:

- The positive effect from the tariffication process.

- The negative effect from the uncertainty created by shifts in the location of production from high to low protection countries. This may create domestic market instability if the shift is to a country with greater production variations.

- The negative effect from the likely reduction in public stocks as government intervention is reduced. The trend will be towards greater private stockholding to fill the gap, but estimates by FAO suggest that only 40% of this gap will be filled. Thus, stock levels are likely to be lower in the future. This has obvious market stability implications but there is also the food security dimension which we examine in Chapter 7.

In response, policy responses could be devised to dampen the impact of such market instability. These are listed:

- The use of Special Safeguards is provided for in the Agreement for countries that opted for it. If you recall from Part I, the special safeguards allow for imposition of additional tariffs whenever prices fall significantly below the Agreement base period of 1986-88 or when import volumes surge. The problem for developing countries is that not many reserved this right as it was only allowed for products subject to tariffication.

- Countries may adopt a sliding scale of tariffs that is inversely related to the level of import prices. This is particularly practical for developing countries who bound tariffs at a high level in order to provide the opportunity for such flexibility. As long as the different levels adopted in the sliding scale are no higher than the rate bound in the Schedule, the action is WTO compliant. To achieve this a price band policy may be used whereby tariffs change only when import prices move outside the band between floor and ceiling prices. As long as the price band is not too narrow, the world price signal is not entirely lost so domestic prices would still move in line with world prices.

However, there is a question of WTO legality with such a policy. The issue is whether the price band mechanism is seen as a "ordinary customs duty" (WTO Legal) or whether it is argued that it is a "variable import duty" (WTO illegal and subject to dispute procedures). To sum, only a formal dispute settlement proceeding can settle this issue. But it is unlikely that a dispute would arise as long as the policy is predictably and transparently implemented.

- A third policy to ensure greater market stability would be to ensure supply stability through the provision of food security measures. As we have seen this is allowed for in the Agreement.

- Article 12 of the Agreement allows a country to place limits on exports provided that the food security of the importing country is taken into account.

- The use of instruments that mitigate the effects of price uncertainty whilst allowing price variability to remain the same. These instruments, such as the use of futures contracts, are WTO compatible.

5.3 Trade policy reform before and after the UR

5.3.1 The trade policy environment in developing countries

As we have seen from the discussion above, economic policy reform programmes have been underway to some degree, for some time in developing countries. Agricultural trade policy reform is an integral part of the success of these programmes. As such, the market access provisions in the Agreement should reinforce the implementation of such reforms. Trade policy reform is likely to support agricultural development via:

- a transparent import policy through tariffication;

- avoidance of undue export promotion of uncompetitive industries;

- an increased role of the private sector in trade decisions i.e. minimising any distortions created via state intervention;

- the removal of overvalued exchange rates that allow domestic sector to compete both domestically and overseas.

From our understanding of the Agreement, we can see that the first two of these factors are addressed explicitly in the Agreement. The latter two will arise from trade policy reforms that support the wider economic reform programme. In this section we examine the trade policy trends in developing countries which existed prior to the Uruguay Round and examine how the Agreement commitments affect the direction of trade policy.

We will now consider border policies with respect to agricultural commodities and examine the influence of the Agreement on these trends i.e. whether they have reinforced, stunted or reversed the liberalisation.

As we have argued, the pattern of agricultural policy in developing countries was tax agriculture. Domestic markets were often highly protected by import controls. The years preceding the Uruguay Round negotiations saw trade policy reforms in developing countries centred on the removal of quotas or licensing restrictions, and changes in the tariff structure. Export promotion policies included:

- reduction of export taxes and quotas;

- exchange rate reforms;

- duty free imports for exporters;

This emphasis on export promotion began a process of moving away from the taxation of agriculture, and the associated disincentive effects on production and consequently export of agricultural commodities.

The implications of the commitments to the Agreement will vary according to the precise nature of the trade policy instruments employed by each country. The matrix presented provides some guidance on the compliance of different trade policy instruments with the Agreement and with the domestic policy reforms usually undertaken in developing countries.

5.4 Policy options under SAPS and commitments in the Agreement: A framework for analysis

The following matrix encapsulates some of the issues we have been discussing so far. The aim is to provide you with a quick overview of the twin compliance stemming from SAPs and the Agreement.

The matrix highlights where policies are neutral with respect to the Agreement and where there may be policy pressures and constraints presented by domestic policy reform as encapsulated by SAP programmes. It also highlights the efficiency and equity issues associated with each policy.

It would be a useful exercise for you to compile a similar matrix to the one shown by looking at the policy instruments currently applied to the agricultural sector, and on specific agricultural commodities in your own country. This will enable you to bring many of the issues discussed in this Chapter and other Chapters in the manual into a more familiar and relevant context.

Table 5.3 A summary of the compliance issues for the domestic policy-maker

| |

Domestic policy environment

|

Compliance with the Agreement on Agriculture

|

Compliance with structural

adjustment programmes

|

Efficiency and equity considerations |

A. Domestic

agricultural policies

1. Output prices

Commodity specific mechanisms using some form of administered price to

support producer prices.

|

* Use of minimum guaranteed prices

for products such as wheat, rice or sugar?

|

Both types of support will influence the AMS, although the de minimis

ruling may exempt commodities with a low degree of positive

protection.

In general, support in developing countries is negative in aggregate. The

AMS may become positive with the removal of implicit Taxation.

However, such support may still be exempt because the de minimis

ruling is based upon 10% of the total value of production and this may

be larger in the case of marketed production. Increasing the

possibility of exemption of positive support to key commodities. |

SAPs emphasise the elimination of producer subsidies or taxes.

If current levels of support are negative such policies do not comply.

Implementation of SAP provisions should lead to removal of the gap between

domestic and adjusted border prices and increasing returns to producers.

|

Minimum price guarantees can provide a degree of price stabilisation which

may increase efficiency.

However, reducing market risk via general output price intervention may

result in an inefficient allocation of resources.

Minimum price guarantees are generally regressive in their impact, favouring those

who market the most, or those able to produce commodities for which support

is most positive. |

|

2. Traded input prices

Actions influencing the prices of seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, machinery

etc. |

* Is there use of input subsidies? e.g. on fertilisers, seeds etc.

NB in most countries this policy tool is being gradually phased out.

|

Input Subsidies generally available to poor

farmers are exempt from inclusion in the AMS. |

Input subsidy elimination is an important part of SAP conditions. Current

policies in line with this therefore comply. |

Such support is potentially more cost effective to administer than output price

support, and it can be used to promote technical innovation, but is a blunt

instrument in that it frequently by-passes the poorest farmers who may not

use these inputs. May be easier to forgo than output price support.

|

|

3. Non-traded input prices

Primarily credit subsidies; also implicit subsidies, taxes on water, electricity etc.

|

* How prevalent is this kind of

subsidy?

* Is there substantial government expenditure on implicit subsidies for areas

such as irrigation water, credit, electricity etc.?

|

Input Subsidies generally available to poor

farmers are exempt from inclusion in the AMS. |

There is pressure from SAPs to eliminate implicit subsidies as well as

general interest rate subsidies since they are not compatible with the

spirit of SAPs. |

Credit subsidies, being input neutral compared with traded inputs, provide a

relatively efficient form of support with substantial scope for targeting

towards the poorest. However, water and electricity subsidies and other

similar support may lead to excessive and inefficient use. |

|

4. Marketing interventions

Interventions which influence the functions of marketing intermediaries and

the financing of marketing costs.

|

* What agricultural commodities are marketed, at least partly, by public

sector agencies? |

Only those

subsidies which �distort� prices of inputs or outputs are the concern of the

Agreement. Therefore, it is neutral with regard to any subsidies which

merely facilitate public sector marketing.

Marketing

subsidies which affect input or output prices are included in the AMS and

considered above.

Subsidies which reduce export marketing costs are exempt.

|

De-regulation and privatisation of public sector enterprises are a

significant feature of SAPs. |

Public sector marketing is often regarded as highly inefficient, although

frequently this is due to a failure to account separately for commercial

and social functions. The latter can be important to areas disadvantaged by

poorly developed physical and market infrastructures. |

|

5. Non-price measures

Direct (�decoupled�) income payments; income insurance; restructuring grants.

|

* Are these measures currently

being operated?

* This is not a common policy instrument in developing countries.

|

Although most �Green Box� policies are not currently applicable, there may

be scope in the future especially with regard to payments under

environmental programmes. |

SAP

conditionality rarely makes reference to this type of policy measure, except

in so far as high levels of government expenditure are discouraged.

At

the same time, environmental considerations are increasingly favoured.

|

In so as

decoupled non-price support does not directly affect resource allocation it

can be an efficient mechanism of intervention.

Direct

income transfers may also be potentially easy to target.

At

the same time, administrative costs may render such interventions

prohibitively expensive in developing countries.

|

|

B. Trade policy instruments

1. Export policies

taxes,

subsidies, and export prohibitions.

|

* Are export duties used?

* Are export subsidies used?

* Are there export prohibitions?

|

Export

taxes do not run counter to the Agreement. However, prohibitions do, except

for health or social reasons, and will hence be hard to justify.

Transport and Marketing subsidies on exports of developing countries are

exempt. For example, a freight subsidy for cut flowers would be exempt.

|

Export taxes and subsidies, in so far as they distort domestic resource

allocation, are frowned upon, although the promotion of export earning

activities are encouraged. |

Export

taxes are a relatively inefficient way of raising government revenue since

they act as a disincentive to export production.

However,

windfall taxes following world price escalation may be justifiable on equity

grounds, and is in the interests of economic stability.

Export

Subsidies may be efficient in the short term (but only in the short term) to

foster market access or, in the small country case, to dispose of atypical

surpluses.

|

|

2.

Import Policies

Tariffs, ,

quotas, other non-tariff barriers, import prohibitions.

|

* Are import

subsidies used?

* Are there import

tariffs?

* Are there import

prohibitions?

* What are the

tariff commitments undertaken in the country schedule?

* Is

there a ceiling binding and gradual reduction commitments?

|

Do current

tariffs fall into the range of commitments undertaken, in the schedules. To

what extent has greater transparency been achieved?

|

SAP

conditionality encourages reduction of tariff barriers and tariffication of

non-tariff barriers, although limited use of tariffs is acceptable at a

common rate.

Import

subsidies provide disincentives to domestic producers and are discouraged.

|

Tariffs are

more efficient than other forms of import restriction, although any

intervention which increases the import price of food is likely to

disadvantage the poorest, particularly the urban poor.

Import subsidies are highly inefficient, since the subsidy benefits foreign

suppliers directly, although the distributional effect, likely to be

ambiguous, may benefit consumers, many of whom are poor, at the expense of

producers, many of whom are also poor.

|

|

C. Public investments

Investment

in research and extension; provision of physical or marketing

infrastructures

|

* How sizeable is

the expenditure on agricultural research and extension?

* What is the percentage of this expenditure in total agricultural subsidies?

|

Expenditure on research and extension is exempt from AMS considerations,

i.e. falls into the �green box� category, as does investment in physical or

marketing infrastructures. |

Investments that aim to facilitate economic and physical infrastructure

development are encouraged, where they are within spending constraints,

especially if they aim to overcome market imperfections while leaving

resource allocation to market forces. |

This type

of investment is regarded as efficient since it facilitates private sector

development, and does not directly affect prices.

At the same

time, public investments are typically long term, and the poor have

relatively short time horizon. Such investments are particularly hard to

target.

|

|

D. Food security measures

Consumer

price subsidies; food stock maintenance; food aid provision.

|

* What consumer

subsidies are in operation?

* For example, are products/commodities such as wheat, edible oils and sugar

affected by consumer subsidies?

|

The

Agreement is neutral with regard to consumer subsidies, so these do not

affect compliance.

Neither do the maintenance of food reserves (which are not used to support

producer prices) or the provision of foodstuffs at subsidised prices.

|

SAPs

generally require the curtailment of public spending, particularly on

consumer subsidies.

Conditionality is likely to require the reduction or elimination of consumer

subsidies.

|

General food subsidies are highly inefficient since the poor and non-poor

may benefit equally. Such leakages are reduced through targeting, but the

associated administration costs are likely to be high. |

5.5 Concluding comments

The structural adjustment reforms undertaken have encouraged greater reliance on private sector activities as well as fiscal and monetary austerity. Increased competition to foreign competition has been often a key feature. The tariffication process and the other commitments of the Agreement have, on the whole, reinforced this process. It is argued that the gains for developing countries from incorporating agriculture under the trade rules of the WTO, will come in the long run via more secure markets and more stable agricultural commodity prices in particular for food commodities.

The impact of the Uruguay Round Agreement on any country will primarily depend upon its domestic economic environment in conjunction with changes in external prices or markets. The central task faced by Policy-makers is to ensure the transmission of any benefits of the Agreement to domestic producers and consumers, as this will determine the extent to which higher and more stable prices, improved transparency, and greater market access are translated into improved incentives to domestic producers and investors. Thus, agricultural trade reforms combined with macroeconomic reforms which enhance the efficient use of scarce natural, human and financial resources are critical in ensuring the maximisation of the opportunities created by the Agreement.

|