Concept 2: Socio-territorial units

Concept 3: Residential patterns

Concept 4: Production system and sub-systems

Concept 5: Socio-economic strategies

Through its work, the SEU has attempted to clarify and work upon a number of basic concepts which have far-reaching implications for development.

In addition to providing a clear conceptual framework for the research process itself, an understanding of these concepts and their inter-linkages contributes greatly to the elimination of sources of confusion in the implementation of development activities.

Seven basic concepts have been retained: kinship groups, socio-territorial units, residential patterns, production systems, socio-economic strategies, poverty and impoverishment, and culture.

The social structure of communities in Balochistan is made up of groupings essentially based on kinship. Individuals characterize themselves as part of these groupings, sharing ideology and cultural values. Kinship links permeate individual behaviors and collective attitudes.

Membership in descent groups involves collectively recognized rights and obligations of assistance and vengeance.

The main kin groupings are the following:

· the family is the elementary social unit established by marriage, and constituted of a couple and their children

· the lineage (called zai in Pashtun) is a localized and unified group of families who can trace links of common ancestry;

· the clan (aziiz) is a group of lineages which claim common ancestry, though without necessarily being able to trace it;

· a number of clans form a tribe (khel), a more general structure whose members consider themselves culturally distinct from other such units;

· tribes are parts of larger, usually regional, political structures, which may be called 'confederacy' or 'confederation' (kom) (such as the Kakar confederacy of Pashtun).

The individual perceives himself/herself within a set of concentric circles. At the center is the immediate world of daily social interactions. The intensity of integration and sociability diminishes as one moves farther and farther away from the center, i.e., as the fields of social relations expand at a higher level of social organization.

Social organization, at least in the case of Pashtun, is characterized by an egalitarian ethos positing tribes, clans and lineages, as well as individuals within these groupings, at the same level. Society is thus conceived along the model of brotherhood. The notion of brotherhood can entail conflict as well as cooperation as an over-arching authority is lacking.

R The ideology of 'kinship group' helps explain the behaviors and practices of individuals at the local level. For instance, the Pashtun communities the IRLDP is working with are prone to individualism and schisms. Each individual family head may pursue activities perceived in terms of his own family's interest beyond any form of tribal and clanic solidarity. These behaviors have to be taken into account in the context of development initiatives based on a community-oriented approach. |

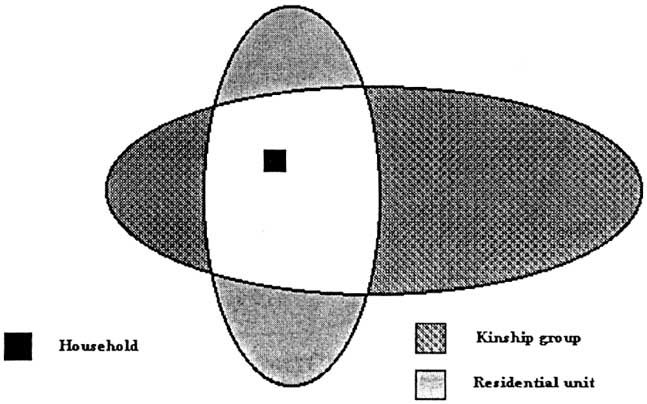

In the course of its work, the SEU soon realized that, while kin groups strongly affect the life of individual members, kin ties are not the unique ensemble to which individuals belong. In fact, alongside of their affiliations to clans and tribes, individual households tend to identify themselves as small residential units with or without kinskip links.

In addition to the traditional kin relations, concrete economic forms of cooperation and solidarity between households may shape new links within more or less homologous neighborhoods. Thus, territorial identification, common interests and common grievances cement communities psychologically and generate an esprit de corps.

Socio-territorial units may thus be identified at the level of an area and/or of a specific territory, with different forms arising from different systems of production and/or specific socio-cultural practices:

· The household (or domestic group) may be defined as a group of relatives (kins and affines), who eat from the same cooking pot (unit of consumption), live in the same compound (unit of residence), and cultivate the same land and manage the same flock (unit of production). That is, a household constitutes the focal point for production, consumption and social life, as well as the basic unit for land and livestock holding, socialization, sociability, moral support and mutual economic help. Age, gender and kinship act as determinants of who does what and who is dependent on whom. A household is made up of one or several nuclear families. A household usually comprises blood relatives from one to three generations (as the lineage). However, contrary to the family, it is not only blood ties, but the total participation in the daily life of production, sociability and consumption which defines household membership. A household includes members who share a common residence and a common estate (that is capital assets, such as cultivation rights, animal holdings and wells, and expendable goods, such as grain, vegetables, milk products, etc.), but also temporary dependents such as brothers, sisters, parents, or even hired workers;

· The village is the basic residential unit. Its components are: the main habitat (usually including several neighborhoods or wards); peripheral hamlets; non-cultivated areas (such as the land under common tenure, called shamilat, the state lands and the public areas); and cultivated areas, i.e., dry agriculture fields and irrigated land, particularly orchards). The village territory includes also various types of water points;

· The pastoral camp is the basic residential unit for pastoral nomadic populations. Its main components are: the summer quarters (garam elaka) in the cooler highlands, the winter quarters (yakh elaka) in the warmer lowlands, and the transhumance routes linking these two seasonal niches.

· Close camps constitute a 'migratory group'! which is a larger network of solidarity and cooperation.

R In a development perspective which takes into account the complexity of the linkages between affiliation to a descent group and membership in a territorial entity, research and development activities need to stress the importance of both kinship and coresidence, two concepts which deeply shape the social life of individuals. In certain circumstances, the residential unit has been found as the most appropriate body to implement and monitor initiatives such as those related to village infrastructures or management of natural resources.. But for other initiatives, such as those involving the use of money (income generating activities), localized kinship groups are more appropriate because of their higher degree of cohesion and solidarity. |

FIGURE 2: Overlapping contexts (The figure illustrates how an individual household may belong at the same time to two overlapping, separate and complementary levels, the kinship group and the residential unit).

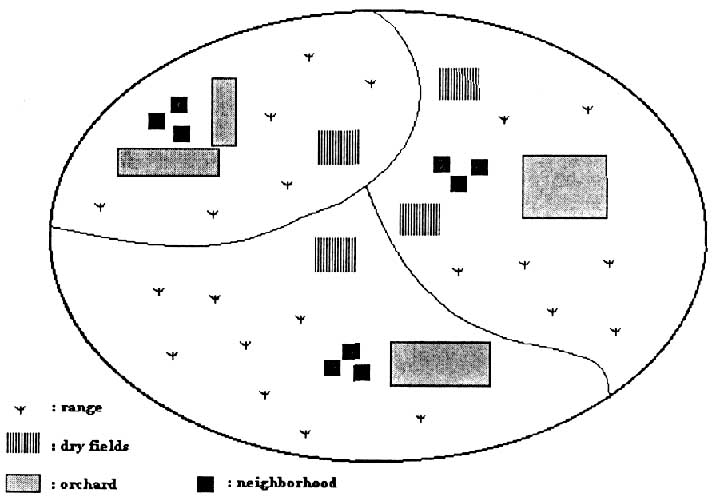

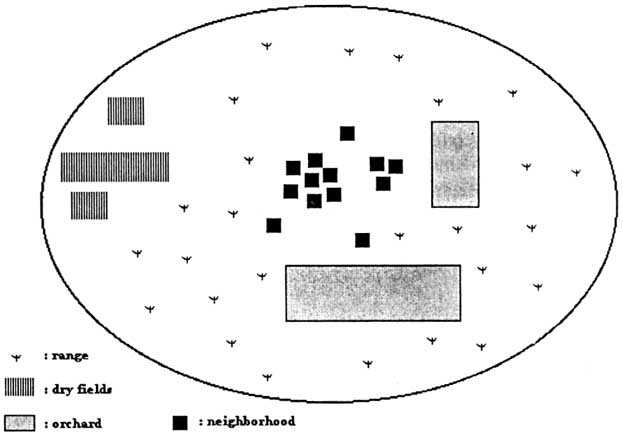

In the pilot areas covered by the IRLDP (inhabited by settled or semi-settled agro-pastoralists), the SEU has found two different residential patterns arising out of different environmental conditions and forms of economic organization characteristic of highland Balochistan.

In the first pattern (see Figure 3), the basic residential units are small groupings of kin-related domestic groups. Although scattered, habitations constitute homogenous neighborhoods jointly sharing the management of their natural resources and maintaining close cooperative links. These neighborhoods do not assume the configuration of a visible village. Kinship links are relatively strong, but social communication (especially among women) is relatively weak. This pattern was found in the two pilot sites in the Loralai district (Asghara-Wazulun valley and Uch Wani).

In the second pattern (see Figure 4), the village is a compact and visible physical entity. Distinct features of neighborhoods are less visible (although each neighborhood may be symbolized by a mosque, a graveyard, etc.). Close relatives do not necessarily live together. This configuration facilitates daily social communication and cooperative links, and serves to promote new forms of relations beyond kinship. In the IRLDP pilot areas, this pattern may be found around Muslimbagh (Qila Saifullah district), in the Kach Mulazai and Ragha Bakalzai areas.

Figure 3: Scattered residential configuration

Figure 4: Compact residential configuration

R Residential patterns strongly affect social interaction and models of cooperation among individuals and households. They have to be taken into account in any development process which aims at creating new solidarities through community-based initiatives which have to be adapted to each context. |

The underlying principle of the work of the SEU is that only a general description and analysis of local production systems may provide a comprehensive view of interrelations between factors of production (labor, natural resources and capital), as well as the social relations between individuals in the productive process.

Contrary to the habit of labelling people as 'rural', landless', 'sedentary' or 'nomads', the SEU has tried to build up its analysis according to a general typology of the production systems existing in the highlands, using economic criteria such as type of agriculture and dependence on livestock for subsistence and revenue. This has led to a typology distinguishing two main production systems (pastoral and agro-pastoral), with various sub-systems (see Table 5).

From an economic point of view, a pastoral production system is one in which at least 50% or more of household gross revenue (i.e., the total value of marketed production plus the estimated value of subsistence production) comes from livestock or livestock-oriented activities. Moreover, more than 20 % of household food energy consumption consists of milk and milk products and meat. This general definition (which applies also to the conditions of production in Balochistan) stresses the economic importance of livestock in pastoral economy.

Agro-pastoralists, on the other hand, are producers for whom agricultural activities take a substantial part of their labor and inputs, but for whom livestock is still an important element for revenue and food as well as a key cultural value. From an economic point of view, an agro-pastoral production system is one in which more than 50% of household gross revenue comes from farming and at least 10 to 15% from livestock keeping. This production system is characterized by the integration of livestock and agricultural activities as an essential strategy in a context in which natural resources are scarce and unpredictable.

TABLE 5: GENERAL TYPOLOGY OF PRODUCTION SYSTEMS IN HIGHLAND BALOCHISTAN

CATEGORY |

DEFINITION |

REMARKS |

PASTORAL |

Households essentially living on animals, usually with other more or less important economic activities. |

Seasonal mobility between winter quarters (mainly in the Kachhi plains and Sibi) and summer quarters (mainly in Kalat, Mastung and Nushki, as well as in the Toba Kakar Range area and in Afghanistan). |

AGRO-PASTORAL |

||

+ subsistence-oriented agro-pastoral sub-system |

Households living on agriculture (mostly rainfed), but considering livestock as an important asset for subsistence. |

A large proportion of households in lower highlands |

+ market-oriented agro-pastoral sub-system |

Household practicing irrigated agriculture (horticulture) essentially for the market, and raising livestock for subsistence and production of revenue. |

Populations in the upper highlands (north- western districts). |

Other categories which a comprehensive socio-economic study should take into consideration are: agriculturalists (with agricultural activities but no significant animal capital); urban-based merchants and civil servants; and transporters; as well as the growing number of 'producers without means of production' (such as landless and livestock-less people, and wage laborers).

R The focus on production systems leads to a careful examination of local potentials and constraints, before the initiation of any development initiative. |

In its attempt to understand local production systems, the SEU has placed particular emphasis on the social and economic strategies adopted by local populations, especially those which are related to production, management of natural resources, investment and survival.

DIAGRAM: 6 ESSENTIAL SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC STRATEGIES AT THE HOUSEHOLD LEVEL

TABLE 7: BASIC STRATEGIES (This table compares the main production strategies of the three production systems)

PARAMETER |

SUBSISTENCE-ORIENTED AGRO-PASTORALISM |

MARKET-ORIENTED AGRO-PASTORALISM |

PASTORALISM |

Practice of dry agriculture |

*** |

* |

* |

Practice of irrig. agriculture |

** |

*** |

- |

Animal husbandry |

** |

* |

*** |

Marketing of produce |

* |

*** |

* |

Use of hired labor |

* |

*** |

* |

Productive investments |

* |

*** |

- |

Mobility of livestock |

* |

- |

*** |

Association agric./livestock |

** |

* |

- |

Productive role of women |

* |

- |

*** |

Degree of socio-economic stratification |

** |

*** |

* |

Search for salaried jobs |

** |

- |

* |

KEY:

- nil

* weak

** medium

*** high

Sequence in the selection of strategies

The SEU research found that there is usually a sequence to what households do in order to produce, survive and cope with crisis. Strategies are planned to cope with risks and responses are not adopted in a random manner. The order in which responses are selected has important consequences for the welfare and very survival of some or all of the household members:

* In normal periods, in order to reduce risks, farmers adopt a variety of techniques to conserve or improve conditions for production (for instance, building small dams, dikes and terraces to reduce water erosion and increase water infiltration), and practice a wide array of activities designed to permit optimal utilization of available resources (e.g., choices of crop species, use of animal manure, etc.);

* At the initial stage of impoverishment, following major ecological and economic crises, households try not to deplete key productive assets (such as land or productive animals), but only assets held essentially as stores of values (such as non-productive animals, jewelry);

* At an advanced stage of impoverishment, poor households try to borrow large sums of money from relatives and to sell their labor force. Furthermore, changes in cropping and planting practices are introduced and current consumption levels are reduced;

* At the initial stage of the destitution process, households decide to dispose of productive assets, normally in the following order: sale of agricultural tools, sale of substantial part of food crop production, sale of productive livestock (females), and sale of significant tracts of fertile land. These strategies usually have the effect of worsening the situation and trapping poor households in a spiral of destitution.

R The study of the strategies of local producers involves not only assessment of individual and collective behaviors and practices, but also measures the potential responses of individual households and groups of homogenous households to development initiatives. Households are likely to respond positively to project initiatives only if their basic objectives and priorities are acknowledged and their strategies strengthened. |

Dimensions of poverty

Findings from the SEU research clearly show that poverty and wealth are always the results of complex mechanisms arising from social, economic and ecological factors which have to be understood in a development perspective.

An important topic considered by the SEU research has been the indigenous notion of poverty. Poverty and wealth are defined in respect to the three elements which regulate the functioning of local production systems, that is natural resources, labor and capital. Thus, poverty is always a lack of resources and/or labor and/or capital. These three dimensions may be considered in combination or independently.

In a development perspective, this analysis leads to a pragmatic definition of poverty through identification of poor households.

R Households are considered poor if: * their income is low (below a specified level which is variable); * they are not capable of self-sufficiency in terms of food security; * they are forced to sell productive assets; * they have to look for wage labor to subsist * they are compelled to borrow money in order to buy food; * they need to purchase grain due to the absence of their own reserves; * they are unable to make productive investments; * they are incapable of producing surplus and investments in assets, constantly living in an unstable equilibrium. |

Processes of impoverishment do not affect all households or communities in the same way. Villages are not monolithic entities and the difference between households may be significant. A relatively advanced process of social stratification and inequality is currently taking place in all rural areas in Balochistan as a consequence of a relatively high monetarization of the economy.

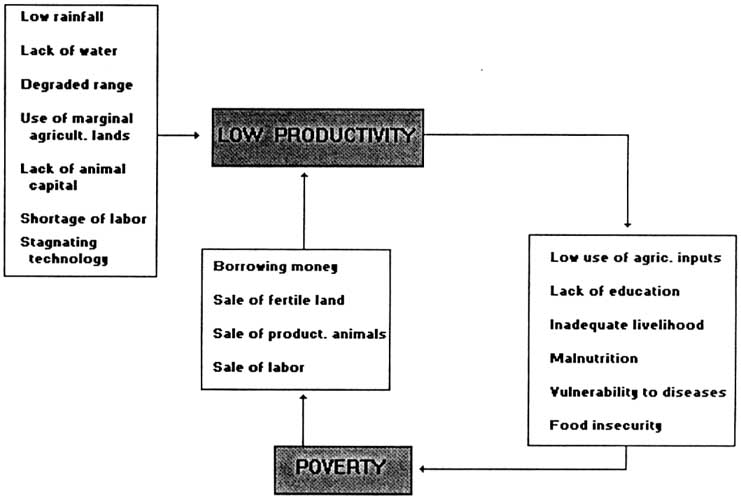

DIAGRAM 8: THE IMPOVERISHMENT PROCESS (This diagram illustrates key elements of the impoverishment process in the changing context of the highlands of Balochistan. It presents some of the causes leading, first of all, to low productivity and, secondly, to poverty and destitution. Survival strategies will eventually have the effect, more often than not, of worsening the situation and leading to lower productivity levels.)

One of the consequences of the impoverishment of large sections of the rural populations is that a relative small proportion of wealthy people may easily control a relative high proportion of the animal capital and of cultivated lands.

Another consequence is the emergence of a large category of destitute people with no capital nor property, who must move to urban areas and sell their labor in order to survive.

Culture may be defined as a set of beliefs, behaviors, and ways of living and acting in society. In the particular context of Pashtun society, 'being a Pashtun' means behaving according to a precise system of values, called pashtunwaali, a social code of morality. It is a concept which covers all kinds of public behaviors and includes everything a Pashtun should or should not do, with rigid requirements.

These cultural values exert a strong influence on behaviors and practices, and, in consequence, affect development processes.

Within the array of cultural values contained in the pashtunwaali, the SEU found that development initiatives based on principles of community particularly contend with those values emphasizing individual male honor and seclusion of women.

An ideology of honor

Among Pashtu-speaking populations, the notions of nang and gherat are essential features to patterning individual attitudes and behaviors as well as interactions between persons and groups of persons. They refer to concepts of "honor', 'bravery', 'esteem', 'reputation', 'name', 'status', 'face', and 'self-expression' or 'serf-determination'. In short, they designate the quality of the person who is not defined by others, but is capable of defining himself, his rights and his property. Together, these notions define the Pashtun man, giving him both an identity and a parameter to judge the behavior and life of other Pashtun. Honor, as a limited good, can be acquired at others' expense. All men wish to avoid losing honor, but many men also attempt to increase their own honor and reduce that of others. Thus, honor is at the root of violence, expressing itself in individual and collective aggressive and individualistic behavior, retaliation and revenge.

Seclusion of women

The honor of a man (as husband as well as father and brother) is strictly related to the control of women (as wives as well as daughters and sisters). This control is expressed in its most extreme form through the imposition of physical mobility and restriction to the private domain (parda), but also appears through various practices aimed at rendering women 'invisible' in the public domain. The relative inactivity and invisibility of their women is considered by Pashtun as the most evident earmark of social status.

Seclusion of women as an indicator of pride and family honor, as well as of wealth, is thus an important feature of the communities the IRLDP is working with. Women are secluded in their courtyards, have to wear a burqa, or veil covering the entire body, are not allowed to leave their compound to visit other households or to participate in social ceremonies in nearby villages. They do not go to market places or even to shops, their direct participation in agricultural activities is limited, as is their role in decision-making and in the management of the resources. They are also denied formal education.

R Culture values may become a crucial constraint in all development initiatives, especially those attempting to set up grass-roots institutions and establish new decision-making mechanisms, as well as those attempting to facilitate the participation of all social categories in the development process without consideration of gender and age. |