Fields of research and relevant findings

Taking into consideration differences between the production systems, the main fields of the research of the SEU have been the following: labor, marketing, and land and water tenure. Findings of this research have significantly affected development initiatives undertaken in the project areas.

RESEARCH

Research on labor has dealt with questions concerning the local division of labor (by gender, age and social categories), and seasonal labor allocations. It has addressed the ways households recruit, mobilize, organize and retain labor, as well as the ways labor limits production. The following are the main questions related to labor:

How is labor used, who does what, how much labor is required, what labor is available, when is it available, is there any competition between agriculture and livestock activities? Other questions relate to social relations in production: who is working for whom, who is working with whom, how the product is distributed? |

MAIN FINDINGS

The labor force is essentially made up of family members, mobilized into age- and gender-specific tasks. Thus, the size of the domestic group and the availability of labor appear to be the most important elements for the economic viability of individual households.

When family labor is not sufficient, especially at certain peak periods of the production cycle, salaried laborers are hired on a daily or seasonal basis. Another way of compensating the lack of labor force in case of need is the organization of one-day group work or reciprocal work groups (called ashar in Pashtu), where relatives and neighbors provide free labor (with expectation of eventual reciprocity).

Table 9 presents the main seasonal activities involved in the productive cycle of agriculture and livestock. Table 10 outlines the main women's activities in an agro-pastoral system, and Graphic 11 illustrates the average monthly labor allocation within individual households.

TABLE 9: CALENDAR OF THE MAIN AGRO-PASTORAL ACTIVITIES (in the highlands)

ACTIVITY |

JAN |

FEB |

MAR |

APR |

MAY |

JUN |

JUL |

AUG |

SEP |

OCT |

NOV |

DEC |

Dry/lood agriculture |

||||||||||||

wheat |

animals grazing in the fields |

weeding |

harvesting |

preparing land |

sowing |

animals grazing in the fields | ||||||

pulses |

planting |

harvesting |

||||||||||

Irrigated agriculture | ||||||||||||

apples |

pruning |

planting |

spraying |

spraying, watering |

grafting |

harvesting |

|

harvesting |

pruning | |||

apricots |

pruning |

planting |

watering |

pruning |

pruning | |||||||

fodder |

watering |

cutting |

cutting |

cutting, watering |

cutting |

watering |

watering |

watering | ||||

tobacco |

preparing seedlings |

preparing seedlings |

harvesting |

|||||||||

Livestock | ||||||||||||

feeding |

lambing |

lambing |

milking |

|||||||||

animals grazing in the fields |

lamb caring |

2nd shearing |

feeding | |||||||||

shearing |

animals grazing in the fields | |||||||||||

to summer quarters |

to winter quarters |

|||||||||||

Others | ||||||||||||

repairing houses |

repairing bunds |

wage labor | ||||||||||

TABLE 10: WOMEN'S PRODUCTIVE AND REPRODUCTIVE ACTIVITIES (example of Pashtun agro-pastoral women in the highlands)

YEAR-LONG ACTIVITIES |

SEASONAL ACTIVITIES | ||||

DAILY |

WEEKLY |

SPRING |

SUMMER |

AUTUMN |

WINTER |

EARLY MORNING: (winter: 06 00-09 00; summer: 05:00-08:00) |

Annual visit to | ||||

Prayers |

Milking |

1st milking |

her natal home | ||

MORNING: (09:00-12:00) | |||||

Fetching water |

Washing clothes (twice a week) |

Taking care of lambs |

|

Collecting firewood stock |

Preparing or |

AFTERNOON: (12:00-18:0) | |||||

Making bread |

Embroidery |

Collecting wild plants |

Making water containers |

Preparing drymeat (landi) |

Preparing dry meat (landi) |

EVENING: (18:00-21:00) | |||||

Preparing dinner |

2nd milking |

||||

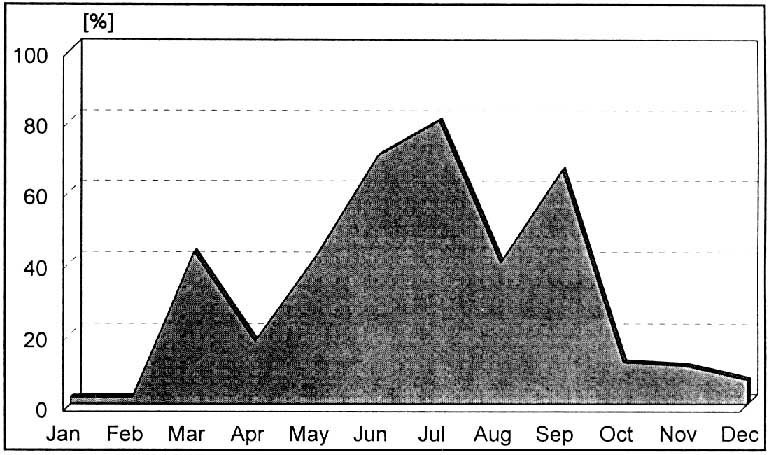

GRAPHIC II: AVERAGE MONTHLY LABOR ALLOCATIONS FOR ACTIVITIES (% of workdays of individual adult members in the pilot areas covered by the IRLDP)

RESEARCH

The market operates as an interface between individual producers and the outside world. Research on the marketing animals and agricultural products has provided information concerning the use of livestock (as productive capital and/or as an assets or a store of wealth) and agricultural products, the seasonal functioning of marketing networks, and the marketing behaviors and strategies of local producers, as well as their relationships with outsiders (laborers, contractors, transporters, etc.).

The main issues which have been explored are:

who sells

what,

where,

when,

how much

and why?

who buys what,

where,

how much,

and why?

Research findings have assisted the project in designing the most appropriate economic incentives for producers, under the general assumption that more efficient marketing systems will encourage producers to participate more actively in market activities, thereby decreasing livestock pressure on rangelands and generating inputs to improve productivity and help rehabilitate natural resources.

MAIN FINDINGS

IRLDP's research found that:

* more than 90-95 % of the products of irrigated agriculture (especially fruits but also vegetables) is destined for market;

* almost all wheat production is destined for internal consumption;

* animal products (milk, hides, skins and, partly, wool) are usually destined for domestic use, with cultural values preventing people from selling them;

* live animals may be sold at different periods of the year, especially by households with low revenues from dry agriculture.

CHART 12: SUBSISTENCE PATTERNS [ The Chart presents the average subsistence patterns of a highland agro-pastoral family of 10

persons, with 6 adults].

RESEARCH

The SEU research confirmed that in Balochistan, ownership or control of land/ water, economic power and political influence are closely inter-related, determining social status and roles.

The analysis of land and water tenure systems may elucidate underlying issues related to access and lack of access to resources, poverty, and the links existing between vulnerability to crisis, impoverishment and environmental degradation.

Data on land and water tenure systems provide indications on how to devise a legal and institutional framework for community use of communal land and water points, together with appropriate economic and social incentives which will guarantee the access rights of rural households to essential pasture and water.

The main research points of the SEU study on land and water are the following:

What are the main characteristics of the land, how is it occupied, used, transferred and inherited; what major types of water points exist and what are the rules concerning their use? Other important questions are related to the ownership and use rights of individuals and/or groups of individuals, the status of communal lands and their control/management by the community. |

MAIN FINDINGS

Land categorization: Three main categories of land have been identified in the highlands:

* the non attributed, non cultivated lands (called shamilat in Pashtu), which are community property under communal tenure. These constitute between 90% and 95% of the total area which is under the control of a community. They are indirectly considered as grazing lands and their use is regulated by the customary rules of the community (nomadic pastoralists are allowed to use these rangelands for free). This land may eventually be divided up and distributed to individuals according to present shares and brought into cultivation;

* the privately-owned land (called malkiat in Pashtu), including lands presently cultivated as well as all other arable lands. Shares of communal lands are allotted to individual households under customary regulations, but only a few people have individual records of property. Land is inherited only by adult males, usually at the death of their fathers. Sale of individual lands to non relatives is prohibited by the tradition;

* the state land (called hokumat in Pashtu). such as reserved forests, which are under the control of governmental departments.

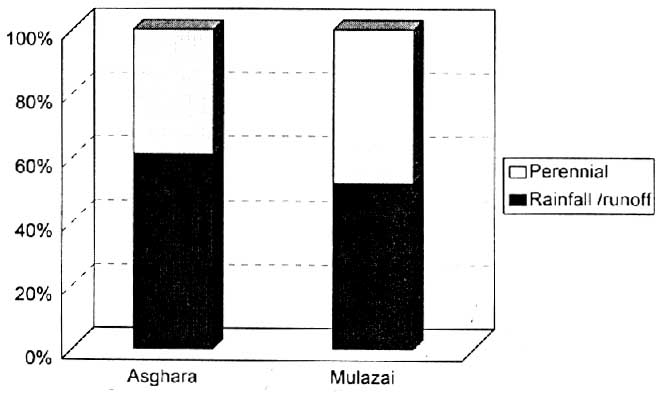

Agricultural land uses Graphic 13 illustrates the main agricultural land uses in the areas covered by the IRLDP. It distinguishes two forms of land uses linked to the type of soil and water, with relative proportions of each depending on a number of factors such as environmental features, availability of water and economic behavior:

(i) rainfed and flood/runoff agriculture with dry-crop agriculture (called khuskaba or barani in Pashtu) made possible only by rains and snow, and flood agriculture (called seilab or neiz in Pashtu) made possible by floods. This form of agriculture is essentially for food crop production destined for domestic use;

(ii) agriculture under perennial irrigation for cultivation of vegetables and fruit trees. The products of these agricultural activities are essentially destined for market.

GRAPHIC 13: AGRICULTURAL LAND USES (in two areas covered by the IRLDP)

About 20 or 30 years ago, the main forms of land use were rainfed and flood agriculture, as the basis of a production system essentially oriented towards subsistence.

But new technological changes have profoundly changed these forces. The commercial orientation of agricultural production has been growing dramatically, constituting the basis of a new form of land use (cultivation of irrigated lands) which has multi-faceted implications (ecological, economic and sociological).

Diagram 14 illustrates the complex process which is affecting a great number of rural communities in the highlands of Balochistan. In this process of change, relatively minor technological innovations may cause a chaine reaction leading to a transformation of the social system itself in line with the features and characteristics of the system itself. It is an example of what sociologists call a 'mixed' process, exogenous and endogenous at the same thee, i.e. derivating from outside and originating from within.

Obviously, this process is not affecting all the areas and all the communities in Balochistan in the same way. For some households, this process is still embryonic or rudimentary, still co-existing with semi-subsistence practices in the context of traditional social relations of production and land uses.

Diagram 14: SEEDS OF CHANGE

Pastoral land use

Among pastoral groups, there is a complex patterns of land use. Land is utilized by different groups according to their particular alternating cycles and different economic objectives.

This pattern of use of pastoral land arises from a system of territorial differentiation, which distinguishes three types of pastoral territories:

(i) the territory utilized by nomadic pastoralists for several months in the summer: this territory, considered as a home-area, is not only a geographical entity, but also an economic, social and political reality. In this territory, pastoral groups have usually traditional land rights (with built houses and cultivated fields);

(ii) the vaste zone being between the summer and winter quarters: this territory is not really exploited by pastoralists, but only traversed in the course of their spring and autumn migrations. Conflicts and disputes may arise between pastoralists and settled villagers who inhabit their territory in a permanent way, holding secure land rights;

(iii) the territory utilized by nomadic pastoralists for a few months in the winter: in this territory, pastoralists co-exist with settled populations who hold secure land rights. Grazing is generally free (both in the uncultivated common lands and in the fields after the harvests). There are no grazing fees to be paid but only general customary regulations to be followed. There are no watering fees, although the use of water points is more strictly regulated than the use of range.

The general rule, with some permutations, is a corporate access to pasture.

Rights to pasture are held collectively by the members of a tribe or a clan, and they include the right to create water points, to use water for animals and people, and the right to graze uncultivated lands. But they do not imply a permanent, private appropriation of uncultivated areas.