1.1 What are food supply and distribution systems to cities?

1.2 Understanding food supply and distribution systems to cities

1.3 Efficiency and dynamism of food supply and distribution systems

Food1 supply and distribution systems (FSDSs) to cities are complex combinations of activities, functions and relations (production, handling, storage, transport, process2, package, wholesale, retail3, etc.) enabling cities to meet their food requirements. These activities are performed by different economic agents (players): producers, assemblers, importers, transporters, wholesalers, retailers, processors, shopkeepers, street vendors4, service providers (credit, storage, porterage, information and extension), packaging suppliers, public institutions (e.g. city and local governments, public food marketing boards, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Transport) and private associations (e.g. traders, transporters, shopkeepers and consumers).

Players need infrastructure, facilities, services and laws as well as formal and informal regulations to govern their decisions. This definition lends itself to the "system" concept: each element influences the other elements in a system of cause and effect, and reciprocal relationships5.

Because the provision of food to a growing city implies food being produced in and transported from rural and periurban areas or imported, an analysis of FSDSs must have an appropriate geographical limit. A system design also needs criteria to characterize what issues are directly relevant.

1.2.1 Key elements of food supply and distribution systems to cities

1.2.2 External and internal factors

1.2.3 The delimiting criteria

The purpose of the analysis of FSDSs is to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each component of FSDSs with the factors influencing their efficiency and dynamism. To improve FSDSs, it is essential to:

1.2.1.1 "Food supply to cities" subsystem

1.2.1.2 "Urban food distribution" subsystem

The various functions performed by an FSDS can be grouped in two subsystems:

1. the "food supply to cities" subsystem includes all the activities that are required to produce food and bring it to cities: production (including urban food production6), imports as well as rural- and periurban-urban linkages (processing, storage, assembly, handling, packaging, transport, etc.);2. the "urban food distribution" subsystem includes all the formal, informal, traditional and modern activities that are required to distribute food within the urban area: wholesale, intra-urban transport, retailing, street food, restaurants, etc.

Production

More food will have to be produced in areas presently under cultivation (if higher yields are possible), from new lands (which are likely to be more distant and less productive) and/or imported (see Table 1.1). This requires increasing private investments and efforts which producers often lacking suitable land, safe water, fertilizers, pesticides, machinery, skills, manpower as well as credit may not be able to undertake. In addition, markets may not be accessible. Private investments in food production are limited also by lack of rural roads to potential production areas and rural markets, required to assemble marketable production.

Urban and periurban agriculture can be an important source of food for some cities, especially when the national food marketing and transportation system is not well developed (see Table 1.2).

Food production in urban and periurban areas has being receiving increasing attention because it can contribute to:

Urban and periurban food production helps cities feed their growing population.

There are a number of problems connected with urban and periurban food production which stem from its close proximity to densely populated areas sharing the same air, water and soil resources. Food production in the polluted environment of cities may cause food contamination. The inadequate use of chemicals, solid and liquid waste in farming can contaminate food, soil as well as water resources used for drinking and food processing. The practice of livestock raising inand close to urban areas may generate health problems to residents. While many of the problems could be solved by information and extension assistance, CLAs have responded by destroying food crops and evicting food producers from public lands under cultivation.

|

Table 1.1 Cities Need More and More Food Increasing quantities and varieties of fresh and processed food are required to meet the needs of urban dwellers. Other requirements are:

Source: Argenti, 2000.

|

For some needs of food producers, see A4.1.

Twenty percent of the Colombo Metropolitan region is occupied by paddy fields and 35 pe cent by highlands crops. Paddy is grown mainly for self consumption. Highland crops, particularly tropical vegetables and fruits, are grown for the urban market. These products have strong demand. During the last two decades many paddy fields have been converted into growing highland crops, especially leafy vegetables. At the same time, some lands have been lost to urban housing and factory construction, especially in Colombo. This trend has been on the increase.

Imports

Cities depend to a varying extent on imported food. Imports require infrastructure, facilities and services, an administrative system and regulations. Issues of relevance to the analysis of FSDSs are: the enforcement of import control regulations for health and environmental purposes, the efficiency of the administrative system for clearing imported goods, dockside storage conditions, the control of imports by importers, etc.

Rural- and periurban-urban linkages7

Once produced, food products need to be assembled, prepared, packaged, stored, processed and transported to urban areas (see Figure 1.1). These functions require skills; assembly markets in rural and periurban areas; handling, packaging, storage, processing and transport facilities; credit to transporters and traders; market information and extension for production and marketing decisions; appropriately enforced legislation and regulations. All such infrastructure, facilities and services need to be efficiently provided and managed. Otherwise, the various costs relating to each of the above elements will be higher than necessary. Post-harvest food losses can be as high as 35 percent in perishable food products.

Table 1.2 Extent of Urban and Periurban Land Used for Food and Agricultural Products in Selected Cities

|

Country |

Land used for food and agricultural

products |

|

Bangkok (Thailand) |

60% of the land in the metropolitan area is in

agriculture. |

|

Beijing (China) |

28% of the city area is used for agriculture. |

|

Beira (Mozambique) |

88% of the green spaces in the city are used for family

agriculture. |

|

Madrid (Spain) |

60% of the land in the metropolitan area is used for

agriculture. |

|

San Jose (Costa Rica) |

60% of the metropolitan area is used for

agriculture. |

|

Santiago de los Caballeros |

|

|

(Dominican Republic) |

15% of the urban area contributes to less than 5 percent of

the city’s food need. |

|

Zaria (Nigeria) |

66% of the city area is cultivated. |

Source: UNDP and FAO.Food assembly

Assembly markets in production areas facilitate both the concentration of marketable food supplies and the encounter of producers and traders. Lack of rural assembly markets means that marketable food products need to be collected from a large number of small farmers at higher costs. Otherwise, these food products cannot be sold.

Produce preparation and food handling

Preparation includes cleaning, sorting and grading. At all stages in the marketing chain produce will have to be packed and unpacked, loaded and unloaded, put into store and taken out again. Each individual handling cost will not amount to much but the total of all such handling costs can be significant.

The Greater Accra region in Ghana is a deficit food production area. It must rely on production transported from the Forest zones, Transitional zones and further north from the Savannah areas. The arable agricultural sector performs erratically from year to year dependent mostly on rainwater. Food imports into the Accra Metropolis to supplement local production shortfalls are a regular feature.

Food packaging

Most produce needs packaging. Packaging serves three basic purposes. First, it provides a convenient way of handling and transporting produce. Second, it provides protection for the produce. Finally, packaging can be used to divide the produce into convenient units for retail sale and to make the produce more attractive to the consumer, thus increasing the final sale price.

Food products may be packed and repacked several times on their way between producers and consumers, depending on the length of the marketing chain. The type of packaging used in a particular country and for a particular marketing chain will depend on the costs and benefits of using it. Thus, plastic crates are likely to be used more for produce marketing in a country where they are manufactured than in a country where a high import duty is charged on such crates. Sophisticated packaging will be used more when it significantly reduce losses; nonperishable produce will not require expensive packaging because the benefits of using it will be marginal. The possibility of using improved packaging made with local materials should always be considered.

Figure 1.1 Rural-Urban Linkages

Food storage

The main purpose of storage is to extend the availability of produce over a longer period than if it were sold immediately after harvest. The assumption behind all commercial storage is that the price will rise sufficiently while the product is in store to cover the costs of storage. Such costs will vary, depending on the costs of building and operating the store but also on the cost of capital used to purchase the produce which is stored. If a store is used to its maximum capacity throughout the year costs will obviously be much less than if it is only used for a few months and is, even then, kept half empty.

Cold-storage facilities are usually insufficient and rent is often high. The few cold-storage rooms built by market managers are often inefficient, mostly because of inappropriate design, or do not work at all, for lack of proper maintenance. Perishable food products, therefore, deteriorate rapidly.

Cold-storage facilities are usually insufficient and rent is often high. The few cold-storage rooms built by market managers are often inefficient, mostly because of inappropriate design, or do not work at all, for lack of proper maintenance. Perishable food products, therefore, deteriorate rapidly.

Food processing

Processing means changing a product’s form, presentation and substance. Processing may occur several times before a given foodstuff is consumed, in advance (after harvesting) or just before the product reaches the consumer (in a food processing unit, a restaurant or as street food). To meet the demand for processed products, there must be:

Processing costs can vary according to the efficiency of the organization doing the processing, the processing facility’s throughput and the frequency of its operation. It will also vary according to the organization’s costs which can depend on factors such as fuel costs, depreciation costs, import duties, taxes and wages.

Processing activities can be an important source of jobs and income, particularly for women (see Table 1.3).

Table 1.3 Importance of Street Food in Selected Cities

|

City |

Consumption |

Value of trade |

|

Calcutta (1995) |

Approx 130 000 street food vending stalls. 33% of the

customers purchase street foods each day. |

Sales estimated at US$ 60 M per year. |

|

Bangkok |

Street foods were found to contribute up to 40% of total

energy intake, 39% of total protein intake and 44% of total iron intake for the

residents of Bangkok. 88% of total daily energy, protein, fat and iron intakes

of children 4-6 years. |

Sales of registered street food businesses exceed US$ 98 M per

year. |

|

Santiago Chile (1991) |

Approx 14, 000 vendors. |

Approx US$ 70 M per year. |

|

Guatemala City (1994) |

Approx 20 000 vendors. |

|

|

Abidjan (1995) |

700 000 street food meals per day in 1993. |

|

Source: ESNA, FAORural- and periurban-urban food transport

In many countries the initial transportation may be the farmer or his labourer, carrying the produce themselves or using animal-drawn carts. Alternatively, traders may send agents around to farmers to collect produce for assembly in one central area. Transport costs will vary according to the distance between farmer and market. But they will also depend on the quality of the roads. A farmer living close to a main highway will probably face much lower transport costs than one living at the end of a rough road which causes much damage to trucks and is frequently impassable. Transport costs will be lower in countries where trucks and fuel are cheap than in countries where import duties are high. Truck owners have to buy their trucks; costs will be lower where bank interest charges are low than where they are high.

For some needs of food transporters, see A4.1.

Frequent road check points and (il)legal taxation add expenses and delays in transport.

Wholesale activities are often dispersed over the urban area, limiting the potential benefits to be derived from organized wholesale markets.

The urban food distribution subsystem is composed of the following elements: wholesale, intra-urban linkages (e.g.: packaging, transport, market information and credit), formal-informal and traditional-modern retailing (markets, shops and supermarkets), street food and restaurants.

For some needs of food traders, shopkeepers, market managers and consumers, see A4.1.

Wholesale markets

Many wholesale markets have not adapted to the increase in food quantities consumed by cities. Most of them were constructed twenty or thirty years ago and are now positioned in areas which urban expansion has transformed in central, high-density spots. This increases traffic congestion and there is no space for market expansion. On-market storage facilities, and particularly cold storage, are insufficient and/or badly managed. Difficulties faced by traders operating in such markets are thus responsible for additional costs and losses as well as increased food contamination. Examples of these problems can be found in cities throughout the world: Accra, Abidjan, Lahore and Santo Domingo.

The inadequacy of wholesale facilities is also an impediment to achieving an efficient FSDS.

While African cities, with very few exceptions, totally lack specific wholesale market facilities, the countries of Eastern Europe and of the Commonwealth of Independent States are increasingly realizing the need for market infrastructure and facilities to support the transition to liberalized food markets.

Markets are often not properly managed and maintained. Funds generated by market fees are not reinvested into maintenance, expansion and better services. This leads to traders feeling that market taxes are not justified and to unrest when rates are increased. Lack of maintenance has been responsible for the burning down of a large number of markets, particularly in Africa.

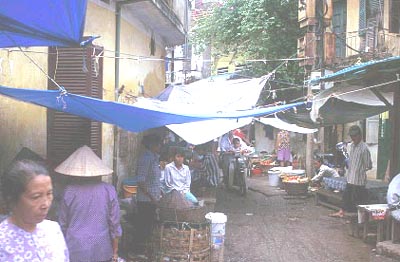

Of the four wholesale markets in Hanoi only Long Bien market was planned, whereas Cau Giay, Bac Qua, Nga Tu So, Trung Hien developed spontaneously, operating along streets in the early morning with no proper market facilities and management. They are all now located in the inner city, wich makes it very difficult for foodtrucks to reach markets as traffic jams are the norms and parking space is insufficient. Market and storage facilities are inadequate and poorly maintained, although traders pay a market fee. The result? High food damage and losses, reduced quality of food, especially for fresh foods and, consequently, higher consumer prices than they need be.

Most informal traders sell in the street because they believe that they can reach more customers. Others do so because they are denied access to market facilities and services, as they are unable to pay market charges. Because of their illegal status, informal traders are often harassed by police.

Intra-urban transport

Food transport from wholesale markets to retail markets and shops can be expensive because of traffic congestion, lack of parking place and the distance to be covered. Perishable products such as fish, meat and dairy products require appropriate transport facilities to prevent food deterioration and contamination.

Retail outlets

The traditional food retail sector (public retail markets, spontaneous markets, formal and informal shops and street vendors) is dominant and central to improving food retailing in cities.

Middle and high-income consumers shop at supermarkets while low-income consumers, who can spend as much as 80 percent of their income on food, go to local shops, to market places near their homes or buy from street vendors.

New market facilities are often badly designed and inappropriately located. They thus remain underutilized and the forced relocation of traders may cause unrest.

Public markets lack professional management and its continuity. Market authorities have insufficient skilled personnel and are unable to enforce regulations. Consequently, trading in public markets becomes more difficult and costly.

Public retail markets

Public retail markets, typically concentrated in city centres, are usually congested, unhealthy and insecure places. Because of this, spontaneous markets are generated which are seen by city and local authorities (CLAs) as a cause of traffic, health and safety problems to cities. They are consequently harassed by municipal police. Most retailers are small-scale traders, predominantly women.

There were approximately seventy two retail markets in Inner Hanoi in the year 2000, 50 percent of which were planned and have market management boards. However, most markets have no parking facilities both for traders and customers. Consumers thus prefer to buy vegetables, fruit, meat, egg and fish from street food sellers.

Public retail markets have not expanded rapidly enough in newly urbanized areas and existing markets have been unable to accommodate the increasing number of retailers. Lack of space or new market opportunities in satellite city districts are thus the cause of spontaneous markets, which fill an important gap in the distribution chain. However, their unplanned nature may create traffic, health and environmental problems. In Dakar, Senegal, three-quarters of the retail markets began on a spontaneous basis. In Lima, Peru, 80 percent have arisen spontaneously, often near slums where there is little availability of public facilities.

Public markets have burned down throughout the world over the last few years because of inadequate structures and maintenance, poor management, fire hazard practices or to force traders into new markets. These blows to the local economy have important financial implications for small traders, entrepreneurs and consumers.

Food shops

In the low-income districts of Latin American cities, a plurality of small, family-run food shops compete for the local market. Such competition, made more difficult by the growing presence of supermarkets and hypermarkets, and the lack of an entrepreneurial mentality as well as technical and managerial expertise, are responsible for low and even negative returns which, in turn, do not stimulate self-development and expansion.

Modern retailing

Supermarkets and hypermarkets, which dominate the modern food retail sector, play only a minor role in urban food distribution in developing economies. Even in Latin American cities, where this sector has developed rapidly since the 1970s, they account for only 30 percent of food retail sales. Supermarkets usually cater for the needs of high-income families, tend to be located in middle- to high income urban areas and distribute mainly manufactured food products and imports. Domestic staples are only a small part of supermarkets’ food sales. They usually rely upon direct contracts with food producers for their supplies, and are thus able to offer lower food prices than the traditional corner shop.

Covering the 800 Km between the Hunza Region in Northern Pakistan and Islamabad requires two days for a ten-tonne truck. Only fruits which can resist such a long trip can be sold in Islamabad. The other highly perishable food and vegetable products (like cherries) can only be transported by one-tonne pick-ups, which reach Islamabad in 10-12 hours, but at cost per kilo six times higher than the one charged by trucks. Producers consequently do not have an incentive to expand production and only rich urban consumers can afford such products.

Informal sector retailing

Many cities have in recent times experienced a steep rise in informal sector retailing (spontaneous markets, sales from home and street vendors), which fill an important gap in the distribution chain. Informal retailers are very dynamic and are usually the only source of food distribution in low-income urban areas where planned markets are absent. Informal activities are a source of employment and income for the poor, particularly women and the youth.

Street sellers tend to be seen as a nuisance by authorities, because they cause traffic and hygiene problems and do not pay taxes.

Street food and restaurants

Street food and small restaurants are an important and convenient source of cheap processed food for low-income urban consumers. They are a source of employment and income for the poor, particularly women (see Table 1.3). Low-income households increasingly turn to street food in time of economic hardship, but street food and small restaurants can be a source of health problems because of contamination risks.

1.2.2.1 External factors

1.2.2.2 Internal factors

The elements constituting FSDSs can be influenced vary various external and internal factors (see Table 1.4 and A4.2).

Table 1.4 FSDS External and Internal Factors

|

External Factors |

|

Internal Factors |

|

|

|

External factors define the situation within which FSDSs operate. External factors are numerous and their importance for FSDSs may vary from city to city. For the purpose of the study of FSDSs efficiency8 and dynamics, it is assumed that external factors are stable in the short run or their change can be anticipated9. The most important external factors are the following:

Urbanization

The economic, political and social framework

The retail marketing system in Colombo includes public markets, fairs, groceries, vendors, hawkers, cooperatives, and Co-operative Wholesale Establishment (CWE) shops. Supermarkets are just beginning to develop in high-income residential areas. The share of cooperatives and CWE shops is estimated at less than 10 percent of the retail trade. Seventeen public markets provide daily necessities to city dwellers, but their importance is being reduced due to an inability to compete with fairs, street vendors and roadside shops. Market competition at the retail level appears to have increased rapidly during the last decade. The recent trend is that food wholesalers retail at lower prices than before. Many retailers reported that their margins dropped to 6-5 percent from the 10 percent level. Although the entry of more retailers is generally seen as a sign of a healthy competitive food distribution subsystem, it has the disadvantage of reducing innovative behaviour, can lead to atomistic competition and higher average operating costs.

Urban food needs

Urban food needs must be met by FSDSs in terms of quantity, quality and hygienic conditions in a context which is experiencing continuous spatial, urban, social and economic modifications. Urban food needs are determined by demographic, economic and social factors and expressed in terms of consumption models and food purchasing patterns which represent the strategies used by urban consumers. Change can result from:

Urban food needs, demand and consumption are concepts based not only on the total consumed, but also on the typology of consumption units (individuals and households). An urban consumption model will consider the characteristics of an average unit. The model must be explained and differentiated by economic and social criteria. The analysis helps determine why a unit purchases a given foodstuff, the quantity, quality, level of processing of the foodstuffs bought and where it is purchased.

Many retail markets in Colombo are poorly designed and badly located (e.g. the market at Delkanda) and were constructed by the Municipality at high cost. As a consequence, pavement traders and weekly fairs near markets are crowded while public markets are underutilized. Consumers prefer the fairs so market occupancy is as low as 50 percent. The local authority has banned the fairs in the evenings following a request made by market traders.

Legal and regulatory framework

FSDS players have to obey laws as well as formal and informal regulations governing: property, contracts, players’ behaviour, the tax regime, rules of enforcement, financial management, etc.

Liberalization and decentralization programmes, that may involve sweeping legal reforms, are often based on an inadequate understanding of the relationship between the Legal and regulatory framework and the functioning of FSDSs (see: Cullinan, 1997 and 1999; Ferro, 1998).

Institutional framework

The institutional framework defines the policy measures and official norms that affect FSDSs and how they are to be implemented. It identifies administrative responsibilities pertinent to various aspects of FSDSs and the territorial levels of competence as well as how policy measures and official norms are to be implemented. It covers decentralization, the role of CLAs and private sector organizations (e.g. chambers and associations) - see Table 1.5 and A4.3, A4.4, A4.5, A4.6 and A4.7.

|

Table 1.5 Role of Civil Society Organizations in Improving FSDSs

|

This group includes infrastructure, facilities and services such as transport, communication, security, electricity, water, etc., which are developed for society at large but which are used by FSDS players.

The characteristics of rural, periurban and urban areas

The agronomic, spatial and urbanistic characteristics of rural, periurban and urban areas determine where food is produced, the availability of new production areas, their distance from consumption centres, the location of FSD infrastructure within these areas, etc.

Good market management, maintenance and upgrading are as important as raising revenues.

Hanoi is currently importing from other areas pork, chicken and vegetables (20%), fish and fruits (50%), eggs (60%) and fresh milk (80%). Urban growth also entails the loss of productive land in the suburban areas. Thus, food supplies will increasingly come from areas further and further removed from Hanoi markets at an obviously higher cost.

Internal factors drive the FSDS from within.

They are affected by but do not directly influence external factors. The most important internal factors are the following:

Urban consumers’ food consumption and purchasing preference

Urban households food consumption patterns are determined by numerous factors, the most important of which are income, taste, prices and social values.

Urban consumers buy food from public retail markets, shops, street vendors, supermarkets and restaurants. Their choice is determined by prices, taste, convenience, credit facilities by the retailer, cleanliness, costs of accessing alternative retail outlets, etc.

For details of the needs of consumers, see A4.1

Plans to develop market facilities away from urban centres often result in underutilized markets. This may be due to:

Players and their strategies

All the players involved in food supply and distribution activities and services have particular objectives (e.g. earning an income, expanding or maintaining a certain level of economic activity, reducing risks and restricting competition) that they try to attain through various means and strategies. Such types of behaviour are influenced by economic, social, individual or group factors and determine the economic trading conditions. As the public and private institutions and agencies involved in FSDSs act as players, their policies need to be examined to reflect public or group strategies.

Characterization of the players in economic, legal and social terms (e.g. sex, ethnic group, religion and family) helps towards an understanding of the players’ economic operations and behavioural patterns.

Electrical systems in markets often generate fires.

Market authorities usually guarantee cleaning inside the markets, but this is rarely adequate. Toilet facilities are rare and seldom properly cleaned. Water points, drainage and sewage are usually insufficient. Inadequate lighting in markets exposes users to additional risks and increases the likelihood of theft.

Food products flows

As food demand increases and is differentiated, more food (quantities and varieties) must reach urban consumers. This requires changes in the supply conditions, marketing and distribution infrastructure, facilities and services, as well as in all other activities through which urban food needs are satisfied. It is essential to understand these flows and their dynamics in order to understand and analyse FSDSs.

Infrastructure, facilities and services

FSD agents need assembly, wholesale and retail markets, storage and transport facilities, etc. which have their internal organization and dynamism that need to be understood.

The disadvantages that emerge when good planning, management, inspection and information are absent include:

Law and regulations

Numerous laws as well as formal and informal regulations relate directly with FSD activities.

Laws and regulations are not often complied with by players because they are inappropriate or insufficiently enforced. In some cases, regulations may become so complex and contradictory that the same CLAs have difficulties understanding and implementing them. This prompts illegal taxation and bribery. Individual FSD activities may not be regulated.

Inappropriate law and regulations can distort and reduce the efficiency of FSDSs, increase the costs of doing business and retard the development of a competitive private sector (Cullinan, 1999).

The rationalization of FSDS may require appropriate changes in the rules governing them10.

Given the numerous factors affecting urban food security, it is necessary to delimit the areas to be studied to those directly relevant to understanding the relationship between urbanization, food security and FSDSs efficiency and dynamism.

The following general criteria may be useful:

1. take the perspective of a city, rather than that of the whole country;All the factors which explain consumption dynamics aid in the understanding of FSDSs. However, the question arises as to how the current urban food model covers the population’s nutritional requirements (see Table 1.6) and whether the gap between expected and actual coverage of nutritional requirements is due to the current FSDS operations or to consumer choice given the available food. This centres on the difference between food availability and accessibility and on the factors which explain consumer behaviour (i.e. purchasing power, food access costs and social relations).2. be concerned with issues that are under the control of CLAs11;

3. focus on homogenous groups rather than individual units (e.g.: the "poor urban households" rather than "individual households", "fruits" rather than "apples");

4. discuss development strategies rather than detailed technological issues (e.g. "how to increase food production by X per cent in the next ten years" rather than "how to cultivate salads", "how to develop small food processing enterprises" rather than "how to obtain marmalade").

The precarious hygiene conditions of established and spontaneous markets, the increasing quantities of waste, and the growing number of lorries required for food transport, have an adverse impact on the environment, as they pollute air and water, increase noise and threaten public health.

This distinction allows to:

A detailed analysis of nutritional considerations or food access and distribution within households are relevant for food security but less so for the analysis of FSDSs.

How to treat external factors

The analysis of external factors should be limited to those capable of influencing FSDSs according to:

For example, the development of a ring road or a railway station will have important implications for the suitability of existing markets or the location of future markets. Consequently, market development plans need to be integrated into the transport development plan: the technical and operational issues involved are similar and the decision-making centres may be set up at the same administrative level12.

What is FSDS "efficiency"?

The efficiency8 of a system is its ability to produce expected results in relation to resources used. FSDS efficiency relates to the following:

The efficiency analysis shows how and to what degree FSDSs fulfil the above conditions. This analysis usually focuses on factors that can change. This ability to change is implicit in the internal factors but modifications can also occur among the external factors.

Table 1.6 Recommended Daily Caloric Intakes

|

Young Children |

Kcal/day |

|

|

|

<1 |

820 |

|

|

|

1-2 |

1 150 |

|

|

|

2-3 |

1 350 |

|

|

|

3-5 |

1 550 |

|

|

|

Older Children |

Boys |

Girls |

|

|

5-7 |

1 850 |

1 750 |

|

|

7-10 |

2 100 |

1 800 |

|

|

10-12 |

2 200 |

1 950 |

|

|

12-14 |

2 400 |

2 100 |

|

|

14-16 |

2 650 |

2 150 |

|

|

16-18 |

2 850 |

2 150 |

|

|

Men |

Light Activity |

Moderate Activity |

Heavy Activity |

|

18-30 |

2 600 |

3 000 |

3 550 |

|

30-60 |

2 500 |

2 900 |

3 400 |

|

>60 |

2 100 |

2 450 |

2 850 |

|

Women |

Light Activity |

Moderate Activity |

Heavy Activity |

|

18-30 |

2 000 |

2 100 |

2 350 |

|

30-60 |

2 050 |

2 150 |

2 400 |

|

>60 |

1 850 |

1 950 |

2 150 |

Source: WHO (1985), reported in Hoddinott, J. 1999.The efficiency analysis must be undertaken on different levels because:

|

Table 1.7 Food Supply and Distribution Costs Farmgate price |

The dynamism of a system is its ability to adapt to changing conditions. This is important as urban food security problems stem from changes in internal as well as external factors.

The important issues are:

Attention should focus on the players’ behaviour.

National legislation and local regulations in Rabat required that fruit and vegetables be transported through a series of wholesale markets where apparently unnecessary yet compulsory middlemen, and a series of market taxes, led to higher retail prices.

Relationship between efficiency and dynamism

Efficiency and dynamism are different concepts. It is possible to have adaptability without being efficient. For example, informal and spontaneous commercial activities show a capacity to adjust immediately to a changing environment. However, poor market and transport infrastructure may result in loss of efficiency, leading to product losses and an unnecessary rise in operational costs as well as health hazards due to poor hygiene conditions.

Economic and social considerations

Rationalization of a FSDS may decrease costs and thus improve accessibility, through lower consumer prices, but entail loss of jobs. This conflict cannot be resolved by the analyst who needs to consider the development priorities set by the state. The analyst may indicate the social and economic costs involved in attaining overall development objectives.

The Rabat market has a monopoly over supplies to the city. The wholesale market was built in 1974, it has no cold-storage and handling is entirely manual. According to the market administration, the Rabat wholesale market handled 104 000 tonnes in 1994, although the total consumption of the city was estimated at 200 000 tonnes. This suggests either underestimation of the tonnage handled or significant evasion of the market monopoly. Analysis of the supply subsystem reveals that the wholesale market operates under an outmoded regulatory system, which hampers its development and undermine its performance in the FSDSs. The main function of management seems to be the collection of taxes. Facilities are clearly inadequate and there is no uniformity or consistency in produce quality. Consequently, prices lose any significance in terms of quality. This undermines transparent dealings in the market. Free circulation of market information is also hampered resulting in producers being poorly informed about market trends. This contributes to sharp inter-and intraseasonal price fluctuations (Tollens, 1997).

Endnotes

1. This term includes cereals, fruits and vegetables, root and tubers, livestock products, fish products, etc., both fresh and processed.

2. This term defines all processing units including animal slaughtering.

3. This term includes butchers and meat shops, among other food shops.

4. Street vending covers the sale of fresh food and processed food. In FAO’s terminology, "street food" only refers to processed food. Consequently, for the purpose of FSDS analysis, "street food" needs to be analysed in terms of two functions: "processing" and "retail distribution".

5. In the pipeline ("filière") approach, operations which succeed one another may be grouped together according to their main functions: production, processing, marketing, distribution and consumption. These functions are managed by players. The pipelines are characterized according to whether they are economic, social or geographic and are influenced by a number of internal and external factors. FSDSs are also defined by the relationships between the players, within a single pipeline, between pipelines and between these and the environment in which they operate.

6. Urban food production refers to small areas (e.g. vacant plots, gardens, balconies, and containers) within the city, used for growing crops and raising small livestock or milk cows for self-consumption or sale in neighbourhood markets. Periurban food production refers to intensive semi- or fully commercial farms close to towns. They grow mainly vegetables and horticultural products, raise chickens and other livestock, and produce milk and eggs.

7. This section contains elements from Shepherd, 1993.

8. An efficiency analysis is based mainly on an economic approach and concerns the market first and foremost. Economics has produced a variety of opinions about theoretical premises and methodological approaches. Researchers are at odds about market performance (Tollens, 1997). For a FSDS case study, the problem consists of transforming the theoretical framework into an operational approach and into a system of indicators tailored to the type of study involved (see also Aragrande, 1997).

9. Some factors, such as economic, legal and institutional frameworks, are static when compared to FSD activities. However, they can change in conjunction with transitional situations such as structural adjustment processes, economic liberalization, administrative decentralization and urban growth. New political, economic or institutional arrangements are often not accompanied by changes in laws and regulations. These are likely to generate conflicts at local level which take time to be solved. The implications of transitional situations for FSDSs must be understood.

10. Economic liberalization, and the consequent dismantling of state-run food marketing organizations, created opportunities as well as difficulties in FSDSs. A proliferation of spontaneous (informal) activities can be observed everywhere. This can be seen as a transitional situation.

11. Some issues that are not under direct influence of CLAs are: the geo-political aspects of international food (grain) trade; cost of international food transport; emergency situations and food aid programmes.

12. One example concerning agricultural policy may help in the understanding of delimitation. Agricultural policy can influence production location and, consequently, consumer prices. In such cases, a national sectoral policy decision affects urban food security (supply opportunities, cost of products and transport, and international competitiveness), but urban administrators do not have the authority to intervene. What is the impact of such a situation on FSDSs when dealing with remote administrative and geographical levels? In the initial stages of the analysis, agricultural policy may be considered simply as an item of data. However, in a dynamic perspective and as the case study progresses, other questions arise:

If the answers are in the affirmative, agricultural policy becomes a significant factor and will have to be included in the analysis of FSDSs in cities as that analysis will provide feedback for national policy. Interinstitutional coordination will have to be envisaged, for various administrative levels are involved. Otherwise, agricultural policy will remain an external element. The situation will be similar in other circumstances (i.e. transport policy and public investment) where delimitation problems arise at geographical, institutional and functional level.