1. Opening of the meeting

2. Administrative arrangements for the meeting

3. Adoption of the Agenda

4. Review and discussion of ongoing work programmes

4.1 Overview of ongoing work-programmes

4.2 Methodologies used by participating organizations to establish the effects and impacts of subsidies

5. Adoption of the report

Mr A. Cox, OECD

Senior Analyst, Fisheries Division

OECD

2 rue André Pascal

75775 Paris Cedex 16

France

Tel.: +33 1 45 24 95 64

E-mail: [email protected]

Mr A. Jalil, CPPS

Comisión Permanente del Pacífico Sur (CPPS)

Av. Carlos Julio Arosemena, Km 3

Edificio Inmaral, 1er piso

Guayaquil

Ecuador e-mail: [email protected]

Mr R. Hannesson

Professor of Economics

Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration

Helleveien 30, Bergen

Norway

E-mail: [email protected]

Mr M. Haughton, CARICOM

Deputy Executive Director

Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (CRFM)

Belize City, Belize

Tel: 501-223-4443

Fax: 501-223-4446

email: [email protected]

Mr W. Schrank

Professor

Department of Economics

Memorial University, St. John’s

Newfoundland, CANADA A1C5S7

E-mail: [email protected]

Ms C. Schroder

Counsellor

Agriculture and Commodities Division

World Trade Organization,

Centre William Rappard

Rue de Lausanne 154

CH 1211 Geneva 21

Tel: +41 22 739 52 47

Fax: +41 22 731 57 60

E-mail: [email protected]

Mr B. Sharp

Professor

Department of Economics, Room 120

Commerce A Building

3A Symonds St, Auckland

New Zealand

E-mail: [email protected]

Mr Somsak Pippopinyo, ASEAN

Assistant Director, Food, Agriculture and Fisheries

Bureau of Functional Cooperation

The ASEAN Secrtariat

70A Jl. Sisingamangaraja

Jakarta 12110, Indonesia

Tel: +62 21 7262991

Fax: +62 21 7398234

E-mail: [email protected]

Mr Stetson Tinkham, APEC

APEC Fisheries Working Group

Lead Shepherd

OES/OMC US Department of State

20520-7818 Washington DC

Tel: +202 647-3941

Fax: +202 736 7350

E-mail: [email protected]

Ms Anja von Moltke, UNEP

Economics and Trade Branch

Division of Technology, Industry and Economics

United Nations Environment Programme

Tel: 41-22-917 8137

Fax: 41-22-917 8076

E-mail: [email protected]

FAO

Mr A. Jallow,

Senior Fisheries Officer

Regional Office for Africa (RAF)

Gamel Abdul Nasser Road

P.O. Box GP 1628

Accra, Ghana

Tel: +233 21 675 000

e-mail: [email protected]

Mr Ichiro Nomura

Assistant Director-General

Fisheries Department

E-mail: [email protected]

Mr J-F. Pulvenis de Séligny

Director

Fisheries Policy and Planning Division

E-mail: [email protected]

Mr Ulf N. Wijkstrom

Technical Secretary and

Chief, Fishery Development Planning Service (FIPP)

Fisheries Policy and Planning Division

E-Mail: [email protected]

Mr Angel Gumy

Senior Fisheries Planning Officer

Development Planning Service (FIPP)

Fisheries Policy and Planning Division

E-mail: [email protected]

Mr Audun Lem

Fishery Industry Officer (Trade Information)

Fish Utilization and Marketing Service

Fishery Industries Division

E-mail: [email protected]

Ms Cassandra de Young

Fisheries Planning Analyst

Development Planning Service

Fisheries Policy and Planning Division

E-mail: [email protected]

Ms Lena Westlund

Consultant

Badhusvägen 13

132 37 Saltsjö-boo

Sweden

Tel/fax: +46(0)8-57028750

Mobile: +46(0)708-548813

E-mail: [email protected]

Welcome to the Third Ad Hoc Meeting of Intergovernmental Organizations on Work Programmes Related to Subsidies in Fisheries.

Several of you have attended one or both of the previous meetings. The first took place in the summer of 2001. We organized it following the instructions of the FAO Committee of Fisheries, which met in the beginning of that year. COFI considered that some savings, and possibly some synergies, could be obtained by bringing together those directly concerned with fisheries subsidies in intergovernmental organizations.

We hope to achieve such effects also in this meeting. And we do look forward to hearing from you about your various ongoing and planned activities related to fisheries subsidies.

In addition, in this meeting we would very much like to draw on the collective wisdom of the group; this to give an appropriate shape to our own work programme.

Our concern is not about what we should achieve - that COFI has told us. In respect of fisheries subsidies COFI recommended that we should focus the Technical Consultation on subsidies to be convened next year on the relationship between fishery subsidies on the one hand and fishing capacity and IUU fishing on the other. So our concern now is: what is the best procedure for generating new and useful knowledge about the relationship between fishery subsidies, fishing capacity and IUU fishing? How should we go about developing such new knowledge?

In order for the meeting to come to some conclusions on these difficult questions we have strengthened the secretariat. We have done so first by asking Lena Westlund to review ongoing activities in IGOs on subsidies. You will have seen the result of Lena’s enquiry in a document that I believe you should all have received before arriving here. Lena has also, in cooperation with our staff, developed some of the details of a potential work programme on fishery subsidies. In doing so we have relied on the work already carried out in our sister IGOs - and we are grateful for the kind reception you gave to Lena during her recent visits in Paris and Geneva.

We have further strengthened the secretariat by inviting to this meeting three well known academicians: Professors Hanesson, Schrank and Sharp. We count on them to help us and give us guidance throughout the development of the practical aspects of our work programme.

I look forward with much interest to the outcome of this meeting. Unfortunately I will not be able to spend much time with you here in the India room, but I will keep myself informed of your progress.

I wish you good luck with the meeting and an enjoyable stay in Rome.

A report prepared for the Third Ad Hoc Meeting of Intergovernmental Organizations on Work Programmes Related to Subsidies in Fisheries held in Rome from 23 to 25 July 2003

Prepared by Lena Westlund

FAO Consultant

|

ACS |

Association of Caribbean States |

|

APEC |

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation |

|

ASEAN |

Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

|

CARICOM |

Caribbean Community |

|

CFP |

Common Fisheries Policy (EU) |

|

COFI |

FAO Committee on Fisheries |

|

CPPS |

Permanent Commission for the South Pacific |

|

CTE |

Committee on Trade and Environment (WTO) |

|

DMD |

The Doha Ministerial Declaration (WTO) |

|

EFTA |

European Free Trade Association |

|

EC |

European Communities |

|

EU |

European Union |

|

FIP |

Fishery Policy and Planning Division (FAO) |

|

GFT |

Government Financial Transfer |

|

IGO |

Intergovernmental Organization |

|

IUU |

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (fishing) |

|

MSY |

Maximum Sustainable Yield |

|

NGO |

Non-Governmental Organization |

|

OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

|

SADC |

Southern Africa Development Community |

|

SCM |

Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (WTO) |

|

UN |

United Nations |

|

UNEP |

United Nations Environment Programme |

|

WSSD |

World Summit on Sustainable Development |

|

WTO |

World Trade Organization |

|

WWF |

World Wild Fund for Nature |

The interest in fisheries subsidies in international fora continues to increase and work on environmental, economic and social effects of subsidies is carried out by several intergovernmental organizations (IGO). On the request of the 24th Session of the FAO Committee on Fisheries (COFI), the Fisheries Department took the initiative to promote cooperation among the different organizations and held the first ad hoc meeting on work programmes related to fisheries subsidies in May 2001. A second meeting was organized in July 2002 and the third meeting - for which this report has been prepared - is scheduled for 23-25 July 2003.

The IGO meetings allow participants to exchange information and to identify opportunities for collaboration. The purpose of the present report is to facilitate this process by giving an account of some of the ongoing work and recent achievements, particularly since the last meeting in July 2002. Chapter 2 presents a summary of plans and progress of work on fisheries subsidies carried out by OECD, UNEP and WTO[4]. A few comments on work by other organizations are also included and some of the academic works published recently are briefly reviewed. The work of the FAO Fisheries Department is presented in Chapter 3. Chapter 4 identifies possible synergies and links between the work of the different organizations and gives suggestions for future cooperation. Concluding remarks are given in Chapter 5.

OECD has several ongoing activities with regard to fisheries subsidies. These are generally coordinated by the Fisheries Division of the Directorate of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries. The Directorate receives its mandate from the OECD Fisheries Committee but it also has close links and collaborates with other relevant directorates, e.g. the Directorates of Environment, of Trade and of Science, Technology and Industry. There is also an OECD Ad Hoc Group on Sustainable Development, whose Bureau is composed of the Chairs of the OECD Committees on Economic Policy, Environmental Policy and Social Affairs. The Ad Hoc Group oversees horizontal work on, amongst other things, environmentally harmful subsidies. The main recent and current activities of the OECD relating to fisheries subsidies concern:

collection of information on government financial transfers (GFTs) in member countries and the study "Transition to Responsible Fisheries";

finalization of the study on fisheries markets liberalization and identification of follow-up work;

environmentally harmful subsidies and how to reduce the obstacles for their removal;

analysis of the broader effects of fisheries subsidies and their relation to sustainable development.

Each of the above four activity areas is briefly presented below. It should be mentioned, though, that there are several issues cutting across the different activities and there are also links to other programmes and studies.

(i) Information on government financial transfers (GFTs) and the "Transition to Responsible Fisheries" study

The OECD Fisheries Committee has made inventories of financial support and economic assistance to the fisheries sector in OECD member countries on several occasions since 1965. As part of a study called "Transition to Responsible Fisheries", GFTs and their impact on resources were reviewed. More detailed data on GFTs were collected for the years 1996 and 1997 and the results were published in the final report of the study in 2000. It is expected that data for the years 1999-2001 will be published in the biannual "2002 OECD Review of Fisheries Policies" and in the future in the annual "OECD Review of Fisheries in OECD Countries".

In addition to collecting detailed information on GFTs, the "Transition to Responsible Fisheries" study also developed a definition of GFTs and a classification system for different types of transfers. GFTs are defined as "the monetary value of interventions associated with fisheries policies, whether they are from central, regional or local governments. GFTs include both on-budget and off-budget transfers to the fisheries sector"[6]. The classification system builds on the different ways transfers are implemented and four main types of GFTs were defined[7]:

direct payments (grants, decommissioning payments, income support, unemployment insurance, etc.);

cost-reducing transfers (fuel tax exemptions, subsidised loans, transport subsidies, income tax deductions, loan guarantees, government payments for access to others countries’ waters, etc.);

general services (research, management and enforcement expenditures, market interventions schemes, support to build port facilities for commercial fishers, payments to producer organizations, etc.);

market price support (generally trade restrictions leading to differences between world market and domestic prices constituting transfers from consumers and taxpayers to fishers).

The fourth category - market price support - although defined and included in the classification framework, was not covered in the study but was later addressed in the fisheries market liberalization study (see below). An additional component, related to the category of general services, was included: cost recovery. This component allowed countries to report on the extent to which management costs are recovered from the industry.

With regard to the impact of GFTs on resources, the results of the study showed that the management regime under which a transfer scheme is implemented is very important in determining its effects. Moreover, it was found that capacity-reducing transfers were often targeting the improvement of industry profitability rather than resource conservation. Nevertheless, it was suggested that capacity-reducing subsidies can reduce pressure on overfished stocks when combined with adequate management measures.

The GFT data collected and reported by the OECD countries have so far mainly concerned the marine capture fisheries subsector. Information on the aquaculture, processing and marketing subsectors has been collected where available but has not been reported publicly to date. Scope for improving data collection in the future has been identified by the OECD Secretariat. The main areas of concern include:

The data reported do not at times include enough details for more in-depth analysis.

There is no independent validation of the information provided by countries.

Information on off-budget support is very incomplete, for example, on fuel tax exemptions and other tax concessions any industry exemptions from fees for services (e.g. harbours, navigation aids, etc.).

Information on regional and local transfers is usually missing; the information reported is often at a national level only.

Market price support is not included.

Untaxed resource rent is not part of the current GFT definition.

(ii) The fisheries markets liberalization study

The document "Liberalising Fisheries Markets: Scope and Effects" was published in early 2003 and presented the results of the study on fisheries markets liberalization. The objective of the study was to analyse "how fisheries trade and production are likely to be affected by reductions in present tariff levels and by changes in non-tariff barriers"[8]. In addition, the study looked into the effects of changes in restrictions on investment, access to services and subsidies. The need to contribute to the WTO negotiations was taken into account when the study was formulated.

The study was carried out by using a step by step approach including (i) description of major markets, products and trade flows, (ii) inventory of border measures, assistance and restrictions, (iii) analytical classification, (iv) identification of linkages (qualitative), and (v) analysis of impact (qualitative). Initially, it was hoped that the impact could be quantified and composite indicators could be developed but, due to lack of appropriate data, these last steps were not implemented.

The study showed that international trade has grown substantially during the last decades. The OECD members constitute the main markets for fish products and there is an important trade flow from developing countries to OECD countries. The structure of tariffs and other border measures in OECD countries is very complex. The study concluded that, generally, relaxing trade barriers would lead to benefits for both importing and exporting countries. However, the effects appear to depend on the circumstances under which the market liberalization takes place, in particular with regard to fisheries management regime and resource exploitation level. The study also identified aquaculture, non-managed shared stocks and high seas fisheries, fisheries under bilateral management agreements, under-exploited fisheries and multi-species fisheries as potentially vulnerable to changes in market structure, i.e. areas in which market liberalization could lead to supply changes affecting trade and resources.

With regard to subsidies to the capture fisheries sector, the results of the study confirmed the outcome of the "Transition to Responsible Fisheries" study and showed that the effect of GFTs on trade and catches also depend on the type of management regime in place; for example, under an effective management system, transfers to the industry would have no effects on catches (Table 1).

Table 1: Effects of GFTs to the fisheries (from Hannesson, 2003)

| |

Type of management regime |

||

|

Open access |

Catch control |

Effective management |

|

|

Total catch |

Increases in the short run but decreases in the long-run if the stock is exploited beyond MSY |

Unaffected |

Unaffected |

|

Long-term profitability of industry |

Unaffected "at the margin" but profits will rise for fishers who are more effective or have lower opportunity costs |

Same as for open access |

Increases |

|

Long-term effects on trade |

Uncertain, depends on what happens to total catch |

Small, but there might be repercussions for goods other than fish |

None |

Source: Page 19, Hannesson, R., 2003, Effects of liberalizing trade in fish, fishing services and investment in fishing vessels. OECD Papers Offprint: No. 8, from Vol. 1, No. 1.

Professor R. Hannesson assisted the study with regard to the development of the analytical framework showing the implications of different management regimes on the effects on trade and resources. However, although this framework helped bringing about some important insights, it was noted that it contains a number of assumptions that do not necessarily reflect the real world and hence restrict the depth of analysis. For example, the framework builds on only a limited number of management regime categories - open access, catch control and effective management - while real management situations are much more varied. It is also assumed that there is complete compliance with existing management regulations, which is rarely the case in reality.

The OECD is now continuing the analyses through its work on environmentally harmful subsidies, and fisheries subsidies and sustainable development (see below).

(iii) Environmentally harmful subsidies

The Fisheries Division’s work on environmentally harmful subsidies contributes to the OECD horizontal programme on sustainable development and is part of a horizontal/cross-sectoral work programme on overcoming obstacles to policy reform initiated in 2001. In November 2002, a workshop was organized with the aim to review methodologies used for measuring subsidies in different sectors, to identify information and analytical gaps, and to define further work. It was agreed that an analytical tool called "the checklist"[9] would be used in a stocktaking exercise and that it should be tested in a number of sector case studies. It was felt that the checklist could constitute a practical method for identifying environmentally harmful subsidies in different sectors even when different indicators and measurements for subsidies are used. Ideally, though, the workshop noted that the identification and measurement of subsidies should be made through environmental impact assessment and a general equilibrium model but unfortunately such a model is not yet available.

The fisheries sector will constitute one of the case study sectors. Work has already been undertaken with regard to the classification of subsidies and on how different subsidies react under different conditions. The analytical framework developed by Hannesson within the context of the market liberalization study is currently being further developed for use in this study. Additional dimensions have been added for bioeconomic parameters, e.g. concerning the level of capitalization of the fleet and the status of the stocks, and different categories of subsidies are examined within this context. The next step will be to apply the checklist and to examine the strengths and weaknesses of the checklist approach in informing the process of subsidy reform. This will be done by using secondary data in case studies looking at particular types of subsidies. The outcome of the work is expected to be a better understanding of the links between subsidies, the management regime and the subsidies’ likely effect on the environment. However, it will not be possible to quantify the environmental effects at this stage and the analysis is undertaken using a number of limiting assumptions and the market structure and demand side are, for example, not taken into consideration. The outcome of the study will be reported to the OECD Ministerial Council meeting in April 2004.

(iv) Fisheries subsidies and sustainable development

The need to analyse fisheries subsidies in the broader context of sustainable development became clear during the work on the market liberalization study. In addition to the work on environmentally harmful subsidies, work will be undertaken more specifically focusing on sustainable development, i.e. with a holistic view covering the three dimensions social, economic and environmental effects.

The work will build on the analysis of the market liberalization study and a previous study on fisheries management costs. It will also have close links with the horizontal work on environmentally harmful subsidies. The enhanced Hannesson framework approach will be used as the starting point. The intention is to develop a matrix - with management regimes and bioeconomic parameters on the two axes - for each type of subsidy and to analyse the environmental, economic and social effects under each set of given combinations. The OECD database on GFTs will be improved and used for the analyses.

While some work has already been done on the environmental and economic impact of subsidies, less is known with regard to the social effects and appropriate indicators will have to be identified for this purpose. Existing - also non-fisheries - work will be used as a basis, supplemented by special case studies with questionnaires designed to collect information from member countries. It is anticipated that this collection of information will focus on national responses to social pressures in the fisheries sector. Information on countries’ broader social programmes affecting the fisheries sector will also be important.

With regard to the analysis of environmental and economic effects, it will be possible to use secondary data to a larger extent than for the study of social effects. However, the section on environmental effects will have broader scope than earlier studies and include effects on, for example, by-catch, benthos, marine pollution, gear use, fuel use, etc. The economic component will assess the economic outcome of subsidies and include effects on costs, revenues, resource rents, investment decisions, etc. An investigation of subsidies related to public goods in fisheries management and infrastructure will also be undertaken.

The three different sections - the environmental, economic and social components - will be brought together in a synthesis report. The expected outcome of the study will be an integrated analytical framework that will provide policy makers with a basis for assessing subsidy reform, both domestically and internationally. This framework will have a strong analytical basis with sound theoretical and empirical underpinnings.

The work on the study started mid-2003 with the preparation of a scoping paper and the identification of key issues. The study will be finalized in 2005.

The work on fisheries subsidies in UNEP is coordinated by the Economics and Trade Branch of the Division of Technology, Industry and Economics. The focus of the work is on the interface between trade and the environment and on enhancing countries’ capacity in various areas related to trade, environment and development policies. The organization’s mandate gives priority to work with developing countries and economies in transition. Within this framework, UNEP is assisting countries in improving their abilities with regard to assessing fisheries subsidies and their impact, and in finding ways to reduce environmentally harmful subsidies. This work has focused on understanding the relationship between fisheries subsidies, overcapacity and the sustainable management of marine resources. The main activities are case studies, development of analytical frameworks for the assessment of impacts of subsidies and workshops.

(i) Case studies

Country case studies on fishery subsidies have been carried out in Argentina, Senegal, Mauritania and Bangladesh. The Argentina and Senegal studies were finalized in 2001 and the results published in the UNEP Fisheries and the Environment series[11]. The reports of the studies in Mauritania and on the marine sector in Bangladesh are still in draft form, currently under revision.

The studies are implemented through 18-month projects and carried out by local institutes and involve a broad range of stakeholders. The objectives of the studies include awareness creation and capacity building alongside the more policy oriented purpose of investigating the impact of subsidies and trade liberalization.

The work has brought about important insights into the likely causes and effects regarding subsidies and resource exploitation. All the studies illustrated that short-term financial gains from trade enhancing policies and subsidy schemes can be offset by longer-term socioeconomic and environmental losses. However, it also highlighted some difficulties in quantifying the effects and distinguishing the effect of subsidies from other practices leading to, for example, overfishing. The analysis has been exploratory and descriptive and constitutes rare examples of empirical field work on this subject matter, in particular in developing economies.

(ii) Development of an analytical framework - the matrix approach

UNEP’s analytical work has focused on the relationship between fishery subsidies, overcapacity and the sustainable management of fisheries. Addressing the environmental impact of fisheries subsidies, UNEP has developed a matrix for identifying these effects under different management conditions (see example in Table 2).[12]

Table 2: Example of Porter’s matrix for identifying effects of subsidies under different management conditions

|

Subsidy type |

Open access |

Open access |

Limited access |

Limited access |

Limited access |

|

Management services |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subsidies to capital costs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Decommissioning and licence retirement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subsidies to foreign access |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Income support |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subsidies to intermediate inputs |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Page 35, Porter, G., 2002, Fisheries subsidies and overfishing: Towards a structured discussion. UNEP Fisheries Subsidies Workshop, Geneva, 12 February 2001. Economics and Trade Unit (ETU).

Based on this analytical framework, UNEP is currently carrying out some further analysis of the actual impacts of different types of subsidies under different management conditions and different bio-economic conditions. For each type of subsidies the following matrix template is being used:

Matrix Template

|

|

Effective Management |

Catch Controls |

Open Access |

|

Overcapacity |

|

|

|

|

Full capacity |

|

|

|

|

Less than full capacity |

|

|

|

The following eight categories of subsidies are used for the purpose of this analysis:

The paper will use examples from developed and developing countries to analyse the effects of these subsidies on fishery resources. An informal expert consultation was organized by the Economics and Trade Branch on 16 July 2003 to discuss this analytical framework. Once the paper is finalized, it will be shared with governments and discussed in a UNEP workshop towards the end of the year.

(iii) Inter-organizational workshops

UNEP has on several occasions organized workshops in consultation with other IGOs. In March 2002, a workshop on the "Impacts of Trade-Related Policies on Fisheries and Measures Required for their Sustainable Management" was held in Geneva. Among the issues discussed, the difficulties of defining subsidies and linkages between subsidies, overcapacity and overfishing received particular attention. In relation to the WTO negotiations, the special conditions, needs and priorities of developing countries were also discussed. The workshop recommended that UNEP conducts further country and regional studies, in particular in cooperation with developing countries and regarding artisanal fisheries. There is also a need for best-practice documents and policy advice for the sustainable management of the fisheries sector. Another workshop will be help at the end of the year in Geneva.

The November 2001 declaration of the Fourth Ministerial Conference in Doha, Qatar, provided the mandate for negotiations on fisheries subsidies and it was agreed to clarify and improve the WTO rules in this regard. The relevant negotiations are taking place in the Negotiating Group on Rules. The WTO members will review progress at the Fifth Ministerial Conference to be held in Cancún, Mexico, in September 2003. According to the timetable set out in the Doha declaration, the negotiations should be finalized by 1 January 2005.

Currently, subsidies in the fisheries sector are regulated in the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM). It specifies that a subsidy exists if "there is a financial contribution by a government or any public body within the territory of a Member" and this contribution fulfils certain specified conditions, or if "there is any form of income or price support in the sense of Article XVI of GATT 1994". Moreover, benefits have to be conferred. For the subsidy to be offending, it also has to be "specific", "prohibited" or "actionable" and cause "adverse effects"[14]. It is argued that these provisions do not cover adequately for subsidies in the fisheries sector since these often are due to production distortions created through unequal access to resources by subsidised and non-subsidised participants in the fishery.

The SCM Agreement obliges member countries to submit notifications of subsidy programmes, including those in the fisheries sector. However, the number of notifications is low and those submitted vary with regard to content and level of detail. Consequently, WTO does not currently hold complete records.

The Committee on Trade and Environment (CTE) has studied the issue of fisheries subsidies for several years, but it is only relatively recently that there appears to be a more substantial move forward in the process.

The state of the debate on fishery subsidies at the CTE is reflected in the Report to the 5th Session of the WTO Ministerial Conference adopted by the Regular Session of the Committee on Trade and Environment held on 7 July 2003 in Geneva. The following five paragraphs are extracted from that report.

There was a general recognition of the importance of achieving the objective of sustainable development in the fisheries sector. It was recalled by a number of Members that the very fact that negotiations on the subject of fish had been launched at the Doha Ministerial Conference was largely based on the preceding CTE analysis. Subsequently, the WSSD Plan of Implementation had reaffirmed the call to clarify and improve WTO disciplines on fisheries subsidies, taking into account the importance of this sector to developing countries.[15]

A few Members maintained that poor fisheries management - taking place under open-access fisheries - coupled with increasing world demand for fishery products was at the root of declining world fisheries resources resulting from over-exploitation and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. In this regard, subsidies could be an effective instrument to reduce capacity, for example through vessel buy-back programmes. One Member stressed that the possible effects of subsidies on resources changed depending on resource status and fishery management regimes. The cases of skipjack tuna, and purse seine fishery in the Eastern Pacific Ocean were referred to in this regard.[16] It was argued that there was a need for flexibility among products when determining tariff levels, taking into account the level of fishery resources and the status of fishery management.

Other Members argued that over-capacity, and, consequently, a significant part of over-exploitation of fisheries, was caused by subsidies. Even when apparently sound management regimes were in place, subsidies could destabilize fisheries management and impede the objective of reducing over-capacity. A high value tuna species was given as an example of a particular fishery which was under a multinational management regime and where stocks had collapsed. It was emphasized that it was the trade measure (the subsidy) that generated over-capacity and needed to be disciplined. Trade liberalization, in concert with sustainable resource management, could stimulate more efficient production with more long-term environmental benefits. Trade barriers in the form of tariffs, or other non-tariff measures, were no substitute for effective resource management.

Most Members stressed that since relevant negotiations were taking place in the Negotiating Group on Rules and the Negotiating Group on Market Access the issue of fish was best left to these bodies. While agreeing that duplication of work needed to be avoided, one Member argued that the CTE needed to monitor the issue of subsidies from an over-exploitation point of view, i.e. an environmental point of view; this had always been the role of the CTE. Another Member pointed out that the CTE could contribute to the ongoing negotiations, while avoiding an isolated CTE discussion, through paragraph 51 of the DMD.

All agreed that more could be done to provide technical assistance in natural resource conservation and management through the various international environmental organizations in the fisheries sector. Some Members reiterated the importance of further studies on the effects of fisheries subsidies and referred, in particular, to the work of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), UNEP and the OECD in this regard. One delegation in particular called for case studies with respect to the impact of subsidies on fishery resources.

Work on fisheries subsidies is also undertaken by a number of other organizations, e.g. NGOs and regional bodies, as well as by individual countries and research institutions. Some of this work was reported on in the last IGO meeting in July 2002, e.g. by ASEAN. Among the NGOs, World Wild Fund for Nature (WWF) has been particularly active and the organization has recently been working on issues related to the new CFP and the EU partnership agreements, and on environmental aspects of the WTO negotiations[18].

In the academic sphere, Hannesson has already been mentioned in connection with his work with the OECD. Hannesson has also written several other papers on subsidies in the fisheries sector, e.g. a review of support programmes in the Nordic countries[19]. This paper looked at the development of subsidies during the 1990s and explored their effect by also looking at the development of catches, fishing fleets and the number of fishermen during the same period. However, the effect of subsidies on landings and on the state of the fish stocks was not clear.

In their paper on the impact of subsidies on the ecosystems of the North Atlantic, G. R. Munro and U.R. Sumaila developed an econometric model for investigating the effects of subsidies under different management regimes[20]. They showed that subsidies could be harmful to the resource also under a property rights system, which is contrary to the commonly held view that subsidies do not increase catches under an effective management system. Moreover, they argued that subsidies that generally are considered beneficial, e.g. decommissioning schemes, could have a negative environmental impact under certain circumstances.

Arnason developed a theoretical, generic, model for examining the impact of subsidies on fishing effort, fishing capital and the economic performance of the fishery[21]. He concluded that the economic benefits from subsidies are in most cases insignificant and that subsidies often lead to increased fishing effort. However, depending on the status of the industry when the subsidies are introduced, the short-term gains to the industry could be quite substantial. He also pointed out that capacity-reducing subsidies could have negative effects unless combined with effective management.

Schrank looked at Arnason’s analysis in the context of tracing the linkages between subsidies and their effects on fisheries resources[22]. Arnason’s analysis focused on profits - resulting from a subsidy programme - and how expected profits lead to changes in fishing effort. The fishing effort, in turn, affects the fish stocks. Schrank suggested that Arnason’s model could be further developed into an integrated econometric model including a marketing sector, a processing sector and a harvesting sector. He also proposed that the effects and costs of fisheries management should be included. Such a model could give indications of the order of magnitude of the response by the fishery to a subsidy programme. However, the data requirements would be considerable. Schrank, Roy and Tsoa developed a model of this type for looking at employment prospects in the Newfoundland ground fishery[23].

As can be seen from the examples of academic work cited above, various modelling and simulation work has been carried out and is still ongoing. However, even though the linkages between subsidies and their environmental and economic impact are understood to some extent, more work is needed for improving the knowledge of the details of the underlying mechanisms. There is also a general lack of data on subsidies and work on quantifying the effects of subsidies is missing. Likewise, very little work has yet been done on the social effects of subsidies or on their impact on sustainable development seen from a more holistic perspective.

It should also be mentioned that there are several issues, closely related to subsidies, on which work is being undertaken, e.g. IUU fishing, fisheries management costs and overcapacity, including decommissioning schemes. It is, however, outside the scope of this report to review these activities.

The FAO Fisheries Department’s work on subsidies is coordinated by its Fishery Policy and Planning Division (FIP). The department receives its mandate from the Committee on Fisheries (COFI). In 1992, FAO pointed out that subsidies were having negative effects on capture fisheries. In the 23rd Session of COFI in 1999, explicit references were made to FAO’s role in analysing these effects and in the end of 2000, an "Expert Consultation on Economic Incentives and Responsible Fisheries" was organized by the Fisheries Department. As a follow-up to this meeting and acting on the recommendations by the 24th COFI Session, a technical tool called "Guide for identifying, assessing and reporting on subsidies in the fisheries sector" was developed last year (2002) as a first step towards an improved understanding of the qualitative and quantitative effects of subsidies. This year, the Department has been asked by COFI to continue the work by looking into the impact of fisheries subsidies on resources, trade and other economic and social aspects of sustainable development. Accordingly, the Department intends to carry out case studies in collaboration with a number of member countries through which the issue can be analysed in an empirical way. A Technical Consultation on the impact of fisheries subsidies will be held in the middle of 2004 to which the results of this work will be presented. Moreover, as mentioned in the introduction and the reason for this document, the department is organising the "3rd ad hoc Meeting of IGOs on Work Programmes Related to Subsidies in Fisheries" on 23-25 July 2003.

(i) Expert Consultation on Economic Incentives and Responsible Fisheries

The preparations for the Expert Consultation included a thorough inventory of ongoing research activities and existing literature on fisheries subsidies and their effects. Four desk studies were carried out reviewing, among other things, forms and definitions of subsidies. In the consultation, the experts were asked to find an operational definition of subsidies and to identify ways and strategies by which more could be learnt about the effects of subsidies in a practical and affordable manner.

The consultation was not able to produce an exclusive definition of fisheries subsidies that could be used for measurement, analysis and political debate. None of the existing definitions in common use were found to be adequate. Instead, it was concluded that four different sets of subsidies needed to be defined. The consultation also concluded that there was very little empirical evidence of the direct casual relationship between subsidies to the fisheries industry and harmful effects on the aquatic resources. Moreover, the current state of knowledge on the magnitude of subsidies and their impact on trade was found to be limited.

(ii) The Guide

As a response to the conclusions of the Expert Consultation and according to the recommendations made by COFI, a Guide was developed for assisting governments and institutions in studying fisheries subsidies. This Guide is designed as a practical and flexible tool for those who carry out studies and prepare reports on subsidies in the fisheries sector. However, the Guide does not cover the analysis of the effects of subsidies on resources, fisheries or trade, but aims at assisting in collecting and organising the data on which these analyses would be based. This covers defining, classifying and quantifying fisheries subsidies as well as investigating the processes by which subsidies are provided. Considering the lack of quantitative data on fisheries subsidies, it was felt that this limitation was a necessary first step towards an in-depth analysis of the impact of subsidies.

The Guide is based on the main principles that were agreed on in the "FAO Expert Consultation on Economic Incentives and Responsible Fisheries". In early 2002, a preliminary draft Guide was prepared, based on available literature and information. This draft was then tested by the carrying out of prototype studies in four different countries after which it was revised to incorporate the experience from the test studies. The definitions and methodologies presented in the Guide were thus developed by combining available theoretical knowledge with practical experience. A final draft version of the Guide was discussed in the "FAO Expert Consultation on Identifying, Assessing and Reporting of Subsidies in the Fishing Industry" in December 2002 before the document was finalized. The document is currently (2003) being printed in the FAO Fisheries Technical Paper series.

The Guide proposes a broad definition of subsidies, including all government interventions - or lack of interventions - that affect the fisheries industry and that has an economic value. This economic value is interpreted as something having an impact on the profits of the fisheries industry. The action, or non-action, should also be something that is out of normal practice, i.e. something that does not apply generally to other industries. The Guide does not take any position with regard to whether a subsidy is "good" or "bad"; subsidies are only seen as government actions, or non-actions, that increase or decrease revenues and costs of the industry.

Four categories of subsidies are defined in the Guide, i.e.:

With regard to assessing subsidies, the Guide uses two complementary approaches for measuring the value of a subsidy: based on the cost (revenue) to the government and estimated according to the value to the industry. These values are often different and in an analysis of the impact of subsidies, it is probably the latter that is of most interest.

The Guide also gives recommendations for how to examine the effect of subsidies on industry profits in more detail, what comparative analyses that could be made with the information collected with the help of the Guide, and how to describe and report on subsidies.

(iii) Country case studies

As a next step in investigating the impact of fisheries subsidies, the FAO Fisheries Department is now planning a series of case studies. The overall objective of the project is to improve the current knowledge of the impact of subsidies and by what mechanisms these impacts are created. More specifically, the intention is that the case studies will give information on:

What impact do different types of subsidies have and can subsidies be categorized according to their impact?

By what mechanisms is impact created and what is the role of subsidies with regard to capacity and IUU fishing?

What particular circumstances influence the impact of subsidies?

How can impact be measured and how can trade-offs between different types of impacts be assessed?

It is expected that the case studies and the analysis of their results will provide a good insight into the above listed issues. However, it is not realistic to expect the work to give final answers. Hence, an additional objective of the work is to clearly identify further empirical and theoretical research needs.

The intention is to carry out 6-8 case studies. They will be carried out in different countries from different parts of the world with special consideration being given to developing economies[24]. While it will be important to understand the overall situation of the fisheries sector in the various case study countries, the focus of each study should be on one particular subsector, e.g. one specific fishery, in order to allow for an in-depth analysis. Moreover, the focus will be on the more explicit subsidies, i.e. direct and indirect transfers and services.

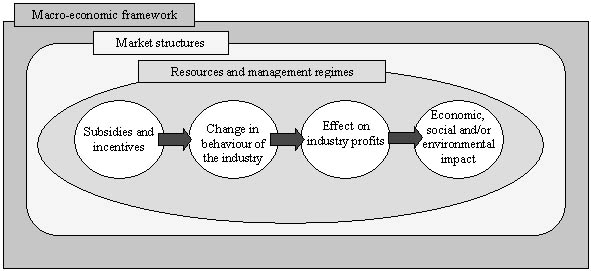

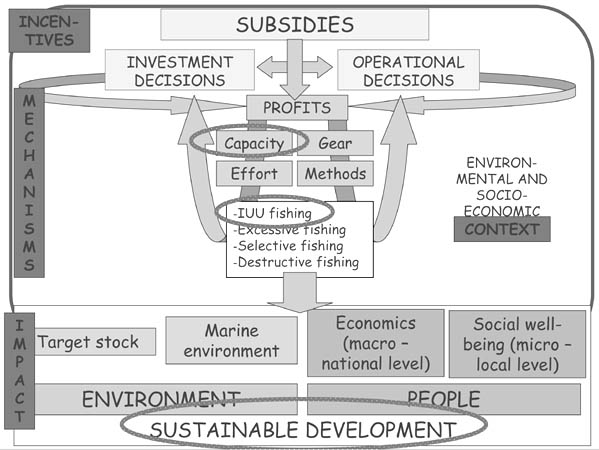

With regard to the conceptual framework and the mechanism for how the impact of subsidies is produced, it is assumed that a subsidy leads to a change in industry profits through the incentives it provides and the consequent change in behaviour which in turn leads to the economic, social and/or environmental impact[25]. This happens within the context of (see Figure 1):

Figure 1: Mechanism and context of fisheries subsidies

In order to analyse the impact of subsidies, these aspects and the links between them would have to be investigated. However, in order to keep the studies within a manageable and workable format, it is necessary to define a limited number of key issues and indicators. These issues and related indicators still need to be clearly defined and should be based on existing economic theory and the current understanding of the mechanisms of fisheries subsidies. Naturally, they should be relevant for the overall objectives of the work. Expected problems with data availability should be taken into account when deciding the level of detail of the analysis and there may be a need to use slightly different indicators in different case study countries. Figure 2 below gives a schematic overview over the different aspects, or dimensions, and what the indicators could be. The indicators should be studied in a historical perspective; the data collection should preferably cover a time series of at least 10 years.

Figure 2: Elements of a study of the impact of subsidies

According to the schema in Figure 2, the data collection will consist of:

Identification and assessment of existing subsidies

This work will be based on the methodologies outlined in the FAO "Guide for identifying, assessing and reporting on subsidies in the fisheries sector". However, only subsidies of Categories 1 (Direct financial transfers) and 2 (Services and indirect transfers) will be included.

Information on the overall framework and in particular on the characteristics of the resources, the management regimes, the market structures and the macroeconomic framework

This information will describe the context in which the subsidies exist and how it has change over time.

Assessment of changes in the state of resources (including vessel capital), in trade and in the livelihoods of the operators (the fisher communities), in the short- and long-term

In the analysis phase, the relations between the different dimensions will be explored according to the defined key issues. The "impact" (on resources, trade and livelihoods - last column in Figure 2) may be explained by a subsidy or/and by other "happenings" in any of the other dimensions[26]. It may be that a subsidy only has a certain effect under specific circumstances. These likely causes and effects will be identified and looked at in a descriptive way and through simple qualitative models as well as by analysing them in the context of existing economic theory and through econometric estimation and modelling techniques. The academic work referred to in section 2.4 above, as well as other similar research work, will be explored in this context. Moreover, particularly with regard to the relation between the impact of the subsidy and the management regime, the results will be reviewed within the context of the findings of the OECD and UNEP studies using the framework/matrix developed by Hannesson[27] and Porter[28].

With regard to the implementation procedure and the time frame, the country case studies will be carried out by local institutions/individuals in cooperation with the FAO Fisheries Department. FAO will provide technical backstopping during the course of the study in the form of visits by a consultant/staff member. Each case study will produce a report covering the results of the data collection, the elements of the analysis and its conclusions as well as a description of the methodologies used and possible problems encountered. Part of the report can be kept confidential if this is a requirement of the host government. The case study reports need to be ready by January 2004. The results of the individual studies will then be explored and synthesized into a final report that will be presented to the forthcoming FAO Technical Consultation. More details on the tentative in-country work programme are given in Table 3.

It is expected that important links can be made between the case studies and work carried out by other organizations and institutions. Lessons learnt by OECD and UNEP in their work will be taken into account. Moreover, it is expected that the work will support the WTO negotiations regarding fisheries subsidies.

(iv) Technical Consultation on Subsidies and Fisheries

The Technical Consultation on Subsidies and Fisheries is scheduled for June 2004. The meeting will be organized in conjunction with two other consultations, i.e. on IUU fishing and overcapacity. According to the recommendations given in the 25th Session of COFI, the fisheries subsidies consultation should also consider the effects of IUU fishing and overcapactiy in the context of effects of subsidies on fisheries resources. Many COFI members also recommended attention to be given to the impact of subsidies on sustainable development, trade, food security, social security and poverty alleviation, in particular with regard to the special needs of developing countries and small island states. Moreover, the consultation should consider how FAO can support the WTO work. It is expected that the outcome of the case studies described above will constitute an important input to the consultation.

Table 3: Tentative program for in-country work - FAO case studies

|

Step |

Tasks |

Time frame |

|

1 |

Agreement with host government and contract established with implementing partner. |

July 2003 |

|

2 |

Data collection - phase 1 - in accordance with methodologies outlined in the Guide: · Subsidies of categories 1 and 2 (see for example sample summary table in the Guide’s Figure 9); · Structure of the fisheries sector (see sample table in the Guide’s Box 22); · Macroeconomic framework (see section 4.3 of the Guide). NB. The data should cover a period of approximately 10 years (while the samples in the Guide show one year only). |

1 month |

|

3 |

Planning of data collection - phase 2: · Review of the data collected and the general data availability and quality. · Selection of the particular segment of the sector that should be studied in detail. · Identification of suitable indicators and variables to be examined with regard to changes in the state of resources, in trade volumes/values and patterns, and in the livelihoods of fisher communities (see examples given in Figure 2). · Assessment of further data collection needs with regard to subsidies, structure of the sector and macroeconomic framework. · Establishment of work and survey methodologies for the continuation of the data collection (e.g. data sources - primary and secondary, sample population, questionnaires, etc). This planning exercise should preferably take place in cooperation with the FIP consultant/staff member during a backstopping visit. |

1-2 weeks |

|

4 |

Data collection - phase 2: according to plan under 3. |

2 months |

|

5 |

Analysis |

1 month |

|

6 |

Preparation of draft country field report |

Deadline for draft report: |

|

7 |

Finalization of country field report |

31 Jan 2004 |

|

Backstopping missions should preferably take place during step 3 (planning of Data collection phase 2) and at the beginning of (or in preparation for) step 5 (Analysis). However, the exact timing of these visits remains flexible since the work is likely to start at different times in different places and since the availability of the consultant/staff member will have to be taken into account. |

||

Reviewing the achievements and work programmes of the different organizations discussed above, a number of common understandings, priorities and concerns are evident, for example.:

Practical policy advice is the most needed end result.

The importance of the WTO negotiations and the need to contribute to this work is generally recognized;

Developing countries have special needs which should be clarified, particularly in the context of sustainable development and the social effects of fisheries subsidies;

The relationship between subsidies, overcapacity and IUU fishing is acknowledged but clear information on the linkages and mechanisms appear to be lacking;

There is a close relationship between subsidies and fisheries management and a subsidy cannot be analysed without also looking at the surrounding management system;

There is a general lack of detailed data on fisheries subsidies and of theoretical frameworks and models by which subsidy data can be analysed. This is true in particular with regard to social effects of subsidies. There is also a general lack of empirical studies on fisheries subsidies and their impact.

The IGOs work on behalf of their membership and the outcome of their efforts should be useful to their member governments. With regard to fisheries subsidies, the demand is for practical policy advice. Considering that our understanding of the impact of subsidies is still fairly rudimentary, concrete policy advice may still be some way off. In the meantime, partial advice may better than no advice at all. It can also be noted that the OECD’s check-list approach is an example of a "short-cut" that may serve as an important entry point and prove useful.

WTO plays a central role for the work on fisheries subsidies since it is the organization with the most extensive powers to enforce new subsidies disciplines, i.e. once negotiations have been concluded and a new - or amended - agreement reached. However, the WTO as an organization does not have the resources and competences to investigate and research the underlying issues in detail and is hence dependent on inputs from its member countries, directly or through other IGOs. This need to contribute to the WTO work is acknowledged by the IGO community and their membership and cooperation is taking place.

The question of the special situation of developing countries and their need for differential treatment with regard to future fisheries subsidies disciplines is considered a concern but so far no concrete proposals have been formulated as to how to deal with the issue in practice. This may be related to the fact that little is known about the effects of subsidies on the social and economic dimensions of sustainable development. Work on these aspects is now being taken up by both FAO and OECD, the latter however focusing on its membership of developed countries.

It is generally accepted that there is a strong relationship between subsidies leading to increased fleet capacity - and overcapacity - and harmful effects on fisheries resources. This relationship, together with trade issues, has been the focus of much of the work up to now, e.g. by UNEP and by academic institutions. The proposals for new subsidy disciplines by the EC, the United States and Chile to the WTO are also based on this concept. Likewise, the influence of the fisheries management system on the effects of subsidies constitutes a core concept in many of the studies. The current work of OECD and UNEP is investigating the theoretical framework further and FAO proposes to include empirical analyses within this context in its forthcoming case studies.

So far, there has been little quantitative work carried out on the effects of subsidies. Efforts are still being concentrated, on the one hand, on the search for theories and models explaining the mechanisms by which the impact of subsidies is created and, on the other hand, on remedying the lack of data on fisheries subsidies. Once more substantial progress has been made in these two areas, the conditions for moving from qualitative to quantitative analysis will improve significantly. With regard to explanatory theories and models, the work by OECD on market liberalization has contributed to understanding the effects on trade and production and so has much of the academic work. The FAO case studies are expected to provide inputs for future quantitative models even though the results to be presented next year are more likely to be qualitative considering the relatively short time available for the case studies. They will also constitute important contributions in the form of empirical work, something that is currently lacking. On the issue of improving the availability and quality of data on fisheries subsidies, the FAO Guide is proposed as a practical tool for facilitating data collection and reporting.

The above overview shows that there is a clear common ground for work on fisheries subsidies and many points of contact between the activities of different organizations. This may not be surprising since all strive in the same direction, i.e. towards a better understanding of the impact of subsidies that eventually can lead to policy advice. However, the mandates, objectives and approaches of different organizations are likely to differ and this section looks into the compatibility of the various methodologies used and their results.

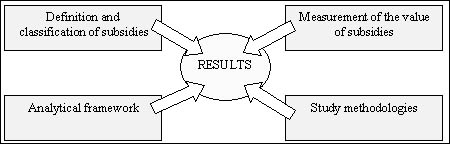

In this context, it may be useful to divide up the work process in different components. Figure 3 shows the five main elements of a subsidies study that will be discussed below: definition and classification of subsidies, measurement of their value, analytical framework, study methodology and results.

Figure 3: Components of a fisheries subsidy study

Most work on fisheries subsidies includes some sort of classification of the different types of subsidies. While there seems to be a common understanding that subsidies need to be classified for analytical purposes, there is as yet no generally accepted classification system; different organizations use different structures. The views also differ between different institutions with regard to the actual definition of subsidies. FAO is probably providing the broadest definition - also including government non-interventions as a subsidy category - while the WTO definition is much more specific. The reasons behind these differences in definitions and classifications are related to differences in mandates and objectives as well as to different analytical approaches. While it would perhaps be difficult to agree on a single set of definitions - which would also probably not be necessary - it could be useful to agree on a common terminology. In any case, the differences need to be noted and care should be taken to avoid confusion.

Different methodologies are also used for the measurement of the value of subsidies. The OECD, for example, measures the value of a GFT as the monetary value of the government intervention, i.e. the direct public budget implication of the transfer. FAO proposes, in its Guide, two complementary measurements: the cost to the government and the value to the industry. The former includes, in addition to the actual budgetary expenditure, the administrative cost (e.g. personnel and overhead) for implementing the subsidy scheme and - in some cases - the capital opportunity cost. The value to the industry can be something quite different and is preferably estimated based on a corresponding market price value[29]. These differences in measurement methods would be likely to create ambiguities if results from different quantitative analyses were to be compared. It would hence appear desirable to agree on common methodologies for quantifying subsidies. However, with regard to the qualitative analyses in many of the current studies, the inconsistency constitutes less of a problem. In this context, the general difficulties in obtaining data on subsidies could be mentioned; there is a lack of reliable and comprehensive information on subsidies - regardless of measurement method used - and this deficiency can only be remedied through increased cooperation from governments.

Looking at the different analytical frameworks and methodologies that are being used, it appears that much of the work currently carried out is exploratory, i.e. more a search for new methodologies than the implementation of existing ones. It is hence difficult to discuss the compatibility or non-compatibility of different approaches. Nevertheless, some common ground is found also here; the basic concepts of the Hannesson framework and Porter’s matrix, mentioned on several occasions in this document, appear to be generally accepted. They do, though, contain a number of assumptions that need to be understood and investigated. If applied in different contexts, care has to be taken when analysing and comparing the results.

With regard to study methodologies, a range of different approaches is used, e.g. case studies, desk studies, qualitative analyses, econometric estimations, etc. There does not appear to be any particular concerns for non-compatibility between different approaches - they rather complement each other - but it could be desirable to carry out more empirical work, i.e. including the collection of quantitative data on subsidies. The specific objectives of a particular activity, or the resources available for a study, will influence the methodologies used. For example, the UNEP case studies (in Argentina, Senegal, Mauritania and Bangladesh) were carried out by local institutions and involved the participation of stakeholders since the purpose of the projects was not only to study the impact of subsidies as such but also to promote capacity building. The results may hence have a somewhat different focus than those of a pure research project. Similarly, the OECD work on developing a check-list for the identification of environmentally harmful subsidies may not lead to quantitative results but may create a practical policy tool.

In summary, it would appear that the results of the current activities of the IGO community are generally compatible with each other and mutually useful. However, as for the interpretation of research results in general, there is a need to understand the underlying methodologies and objectives. For future quantitative work, care will need to be taken to use compatible methods for measuring subsidy values.

Cooperation between different organizations can take place at different levels, e.g.:

It is evident that there is an ongoing exchange of information; the IGO meetings are good examples of this. There are also both bilateral interactions and more informal contacts taking place, and the results of work by one organization is used by others, e.g. FAO’s intention to use the Hannesson and Porter framework/matrix. However, considering the different memberships and mandates of the different organizations, there are naturally limits for the extent to which work can be jointly planned and executed. Nevertheless, it would appear that there is scope for increased cooperation. Some of the issues such cooperation could concern include:

Harmonization of the methodologies used for measuring the value of subsidies, for example by empirical testing of the approaches proposed by the FAO Guide.;

Common efforts to support and encourage countries to collect data and report on fisheries subsidies;

Realization of case studies with joint terms of reference on selected aspects of environmental, economic and social effects of subsidies. This could be an option for the next phase of programming of studies after the results of current OECD, UNEP and FAO studies have been evaluated next year;

Consideration of the possibility to establish an overall priority plan for work on fisheries subsidies, including the identification of the most pertinent research questions and a clear understanding of who does what.

Establishment of procedures for contacts and coordination within the IGO community to ensure that contradictory messages are not conveyed to the different memberships. This aspect will become more important in the future when the results of different studies start to lead to policy advice on a bigger scale.

More and more work is being carried out with regard to the impact of fisheries subsidies and the picture is slowly getting clearer - at least with regard to identifying the pertinent issues to study. However, even more work and concerted efforts are needed to reach a level of knowledge sufficient to constitute a basis for giving sound advice for how to come to terms with the apparent problems with existing subsidy regimes.

Some of the work currently taking place has been presented in this report together with thoughts regarding their interrelationship and future cooperation possibilities within the IGO community. The presentation and the discussions should be supplemented and continued in the IGO meeting and it is hoped that this will lead to constructive results and constitute another step on the way towards understanding the impact of fisheries subsidies.

|

Effects and impacts of subsidies: CASE STUDIES - A work programme proposal Prepared by Lena Westlund 23 July 2003 |

|

Outline of presentation

|

|

Mandate - COFI 2003 FAO/FI should:

|

|

Framework · FOCUS:

· APPROACH:

|

|

What do we want to know?

|

|

Study focus (1) · Focus on a limited number of subsidies that potentially lead to overcapacity and IUU fishing, e.g.:

· Focus on a limited number of aspects with regard to the impact on sustainable development, e.g.:

|

|

Study focus (2) · Focus on marine capture fisheries · Focus on a selected number of aspects of the context that are likely to influence the impact of subsidies, e.g. regarding:

|

|

Study approach

|

|

Study components

|

|

Methodology and data collection (1) Background and base data:

Management regimes:

|

|

Methodology and data collection (2) · Indicators - historical data in time series of approximately 10 years, e.g.: · Capacity and IUU fishing:

· Resources:

· Livelihoods

|

|

Methodology and data collection (3) Quantitative model:

|

|

Programme for in-country work (1) STEP 1:

STEP 2:

|

|

Programme for in-country work (2) STEP 3:

STEP 4:

STEP 5:

STEP 6:

|

|

Expected results · Partial replies to the questions asked, i.e.:

· New research questions defined |

|

Concerns

|

|

Issues to discuss 1. Are the questions asked relevant and realistic, i.e.:

2. Is the focus adequately defined, i.e. with regard to:

3. What analytical procedures and models would be applicable for the analysis?

* * * 5. Are there aspects of the study that could be changed to benefit the IGO community better? 6. Is there scope for closer collaboration, with regard to the proposed case studies or in follow-up work? |

|

THANK YOU!

|

| [4] In addition to OECD, UNEP

and WTO, the following organizations are also invited to the meeting: ACS,

APEC, ASEAN, CARICOM, CPPS, EFTA, SADC and UN Division of the Law of the

Sea. [5] The information presented here is based on meetings with A. Cox and C-C. Schmidt of the OECD Fisheries Division in May 2003 and documents made available at these meetings as well as the OECD official website. [6] Page 4, OECD, 2002, OECD work on identifying and measuring subsidies in fisheries. Prepared by A. Cox for the OECD workshop on environmentally harmful subsidies 7-8 November 2002. SG/SD/RD(2002)5, Paris. [7] In the "Transition to Responsible Fisheries" study, GFTs were also categorized according to the objective of the programme under which the transfer was made, i.e. fisheries infrastructure; management, research, enforcement and enhancement; access to other countries’ waters; decommissioning of vessels and licence retirement; investment and modernization; income support and unemployment insurance; taxation exemptions; and other objectives. [8] Page 3, OECD, 2003, Liberalising fisheries markets: Scope and effects. Fisheries Division, Paris. [9] See Pieters, J., 2002, When removing subsidies benefits the environment: Developing a check-list based on the conditionality of subsidies. OECD workshop on environmentally harmful subsidies 7-8 November 2002 (available at www1.oecd.org/agr/ehsw/). [10] This chapter is based on discussions with A. von Moltke and C. Arden-Clarke of the Economics and Trade Branch in May and June 2003 and on various documents available at the UNEP websites. [11] UNEP, 2001, Fisheries subsidies and marine resource management: Lessons learnt from studies in Argentina and Senegal. UNEP/ETU/2001/7 (Vol.II), Geneva. [12] Porter, G. 2002. Fisheries Subsidies and Overfishing: Towards a Structured Discussion, UNEP Fisheries and the Environment Series, Geneva. [13] The presentation is based on discussions with C. Schröder of the Agriculture and Commodities Division in May 2003, documents made available at this meeting and on information from the WTO website. [14] WTO 1994 Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, article 1. [15] WSSD Plan of Implementation, paragraph 31(f). [16] For more detail, see WT/CTE/W/226. [17] The work cited here does not constitute an exhaustive list of existing activities; only a few main examples are given. [18] See, for example:

[19] Hannesson, R., 2000,

Fisheries subsidies in the Nordic countries. Paper commissioned by WWF. |