|

Domain |

Information users |

Information uses |

|

Finance/planning/trade |

Policy and Programme decision-makers/ Technical staff |

· Development of national policies for promotion of food security and improved nutritional status. · Evaluation of food production and import policies on the basis of recommended population food goals. · Development of food price policies to improve food accessibility among nutritionally vulnerable groups. · Evaluation of sectoral programmes and budgets and prioritizing allocation of resources. Data from the Survey of Living Conditions in Jamaica has had some impact in this area although data are not disaggregated enough and not complemented by food consumption data. · In Guyana anthropometric data from the Living Standards Survey on children under 5 helped to design the national poverty alleviation programme especially with respect to targeting of beneficiaries. · Advocacy to bi-lateral and multi-lateral donors to target resources for poverty alleviation. · Awareness-raising/advocacy to policy makers about health and nutritional implications of development strategies. · Review existing fiscal and trade policies to facilitate healthier dietary choices and activity patterns. · Selection and incorporation of food nutrition-related indicators in monitoring national development goals. |

|

Agriculture/fisheries |

Policy and Programme decision-makers/Technical staff |

· Formulation/evaluation of food production goals & policies on basis of recommended population food goals. · Strengthening of linkages between agriculture and nutrition at strategy and programme levels. · Review of local food production and distribution systems and development of strategies/programmes for improving diversity in domestic food supply in light of consumption patterns & recommended goals. · Planning and monitoring of targeted agricultural interventions with food security and nutritional objective. |

|

Health |

Policy and Programme decision-makers/Technical staff |

· Awareness raising/advocacy to public and private sectors and civil society re health and economic benefits of interventions to prevent and combat nutrition-related problems. · Development and promotion of dietary guidelines. Guyana will be using data from their survey to guide the development and dissemination of guidelines · Strengthening and reorientation of health services to address nutrition and diet related problems. · HRD policies for nutrition services. · Identification of extent and severity of nutrition problems and vulnerable groups. · Assessment of adequacy of dietary intakes of different population groups. · Planning/evaluation of intervention programmes. · Development/review of norms and standards for nutrition and dietetic services. · Establishment/strengthening of nutrition surveillance systems. · Review existing policies, laws and regulations which impact on dietary and lifestyle practices. · Development/evaluation of educational messages and communication strategies. |

|

Education |

Policy and Programme decision-makers/ Technical staff |

· Awareness-raising among planners of impact of food and nutrition problems on educational performance. · Incorporation of objectives and strategies for promoting improved nutrition and activity patterns in sectoral plans. · Selection of procedures for nutritional and activity assessments as part of school health services. · Incorporation of relevant knowledge/skills/attitudinal objectives aimed at promotion of healthy eating and activity patterns in design/revision of curriculum at all levels. · Review/evaluation of school feeding and cafeteria menus based on recommendations for improving dietary practices. · Awareness raising to stimulate community interest and action in improving food and nutrition. |

|

Training institutions (Tertiary level) |

Heads of faculties/departments |

· Training needs assessments in relation to combating food and nutrition problems. · Review of curricula and preparation of training materials. |

|

Researchers |

Academic researchers; epidemiology units and research departments in line ministries |

· Identification of research topics and questions for fuller understanding of problems and issues (e.g. studies on: trends, determinants and health and economic costs of nutrition-related problems; implications of trade and other sectoral policies on household food security; determinants of dietary behaviour change; testing of nutrition education intervention approaches). |

|

Mass media |

Print, broadcast and electronic media personnel |

· Preparation of features to increase public understanding of food and nutrition issues; to solicit ideas, opinions on contributory causes and solutions. |

|

Private sector |

Food manufacturers, processors, retailers, food service managers |

· New product development and promotion; fortification and enrichment schemes. · Review of purchasing and distribution options to meet identified gaps in food supply system. · Menu-planning in food service establishments. |

|

Civil society |

NGOs, CBOs, professional associations, consumer groups |

· Advocacy to government, private sector and donors. · Project preparation. · Social mobilization. · Community education. · Review of professional practice guidelines (e.g. medical care). |

|

General public |

|

· Increased awareness of food and nutrition-related problems. · Self-evaluation of food choices and dietary patterns. · Empowerment and participation in public debates on food and nutrition issues. · Advocacy for increased accessibility to nutrition services. |

|

Donors |

Bi- and multi-lateral donor |

· Establishing priorities for technical cooperation and assistance country programmes. · Preparation and monitoring of technical cooperation projects. · Policy advocacy. |

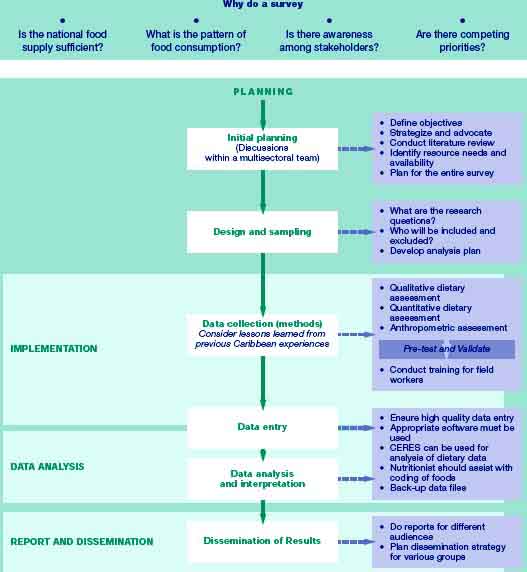

PLANNING

Set out below are some issues to consider at this stage.

Have you:

defined objectives?

established research questions?

developed an implementation plan and timeline covering all stages of the survey?

developed a data-analysis plan?

established strategic partnerships?

established a survey committee?

undertaken a literature review?

considered all potential uses of the data?

Sampling strategies

Have you:

sought advice from a statistician regarding the proposed study design and sample selection? e.g. Statistical Department?

determined inclusion and exclusion criteria of participants?

included additional samples based on expected non-response rates?

contacted the Census Bureau and Nutrition Monitoring Board?

inspected the survey areas?

Methodology

Have you:

selected an appropriate dietary assessment method?

developed the data collection instrument (s)?

considered how the method will be validated?

developed a manual of procedures for sample selection and data collection?

Resource needs

Have you considered all human resource needs required?

Coordinator/manager;

field supervisor;

administrator;

trainer;

nutritionist/nutritional epidemiologist;

anthropologist or other qualitative researcher (if necessary);

recipe data collection staff;

portion size-collection staff;

data manager;

data coder;

data-entry clerks;

data analyst;

driver (if necessary).

Selecting and training personnel

Have you:

developed the criteria for selecting personnel?

developed a training manual?

allowed adequate time in the activity plan to train and to observe the trainees in the fieldwork?

Equipment

Have you:

identified all your equipment needs? e.g. scales, stadiometers, length boards, measuring tapes?

ensured that they are appropriate for your target population?

identified suppliers and requested quotations?

ensured enough lead time in placing orders?

Ethical clearance

Have you:

drafted consent forms to be completed by participants?

obtained the necessary clearances from the relevant bodies? (This can be a lengthy process so plan for it.)

IMPLEMENTATION

Piloting and pre-testing all data collection instruments and equipment

The importance of pilot testing all aspects of the project can not be over-emphasized as this will highlight any difficulties before the study begins. All aspects of the project should be pilot tested from data collection to data analysis.

The pilot study should explore and test:

communication between target groups and survey staff;

questionnaires and materials;

transportation;

arrangements of appointments and work schedules;

time taken to complete questionnaires;

supervision of data collection and checking;

transfer and storage of survey records;

data entry software;

preliminary data analysis.

Have you allowed time and resources for pre-testing the:

dietary assessment instrument?

anthropometric equipment and recording sheets?

recipe-recording forms?

scales?

portion-size recording forms?

Data collection

Have you:

developed a time line?

organized data collection schedules?

determined a recruitment strategy?

considered printing of questionnaires?

purchased equipment?

organized transportation?

decided how you will contact participants?

considered supervision of data collection?

made arrangements for storage of survey records?

developed a method for keeping track of non-responders?

thought of strategies for keeping interviewers motivated?

prepared a schedule for frequent meetings with data collection staff?

Data entry

Have you:

considered the software options and decided on the software package to use?

allowed time and resources for familiarizing the data-entry personnel with the data-entry programme by entering pilot data before the study begins?

developed a tracking system for the survey records?

considered who will code the questionnaires and when?

developed a system for data entry and checking including backing-up of data?

Data analysis

Have you:

finalized the research questions based on the original research questions?

considered how the results will be presented (tables, charts, figures)?

decided which software package to use?

considered whether additional software is needed for analysis?

considered whether the various software packages being used are compatible?

Dissemination of results

Have you considered different dissemination strategies?

Reports for government;

public seminars;

presentation at conferences;

publications;

feedback the results to the community.

BUDGET

Personnel costs

Have you included:

personnel salary and benefits?

personnel recruitment cost?

personnel training cost?

trainer (transportation, housing, meal per diem, honorarium)?

trainees (transportation, housing, meal per diem)?

Office expenses

Have you included:

office rental?

electricity and other utilities cost?

custodial and security services cost?

filing cabinets and other storage space cost?

telephone?

mail service?

fax machine?

internet connection?

Field expenses

Have you included:

field office rental?

field office supplies?

transportation (public transportation fares, gasoline, vehicle rental, vehicle insurance)?

supplies for field workers: food scales, backpacks, clipboards, notebooks?

housing allowances?

incentives for respondents?

Data analysis

Have you included:

computer?

printer?

software for all data?

software for analysis of nutrients data?

Dissemination

Have you included:

airfare for conferences?

hotel cost?

conference registration fee?

taxi?

per diem?

phone and e-mail service cost?

publication cost?

printing of reports?

HUMAN RESOURCES

For each phase of the project personnel need to be identified, recruited and trained. Personnel needs - from data collection through data analysis - need to considered.

The following personnel may be necessary - some of the personnel needs could be combined.

Project coordinator/manager;

Field supervisor(s);

Administrator, for handling budgets;

Biostatistician/programmer;

Nutritionist/nutritional epidemiologist;

Anthropologist or other qualitative researcher;

Nutrition-data collection staff - for 24-hour recall, food diaries or food frequency questionnaires;

Recipe-data collection staff;

Portion-size collection staff;

Anthropometric data collection staff, male and female;

Driver;

Data manager;

Data coder;

Data entry clerk.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE SELECTION AND TRAINING OF PERSONNEL FOR WORKING IN FOOD CONSUMPTION AND ANTHROPOMETRIC SURVEYS IN THE CARIBBEAN

Based on the Caribbean experiences, the following are recommendations for the selecting of supervisors and field personnel.

Some criteria for selection of supervisors

Good references;

relevant experience;

good interpersonal skills;

good communication skills;

flexibility - willing to work long hours when necessary and weekends;

honesty;

motivated;

leadership skills;

management skills;

ability to work full time;

selecting as supervisors those field workers who excel in training and providing additional training.

Desirable characteristics of field personnel

Polite and friendly;

flexibility with working hours as fieldwork depends largely on respondents' hours of availability;

familiarity with the community;

familiarity with the languages used in the area;

previous experience;

able to do strenuous field work.

Recommendations for training staff based on Caribbean experience

Training should be mandatory;

develop a training manual;

allow adequate time to train and to observe the trainees in the fieldwork;

evaluate the difficulties in the training and address these before the study begins;

ensure that the trainees have been trained in how to introduce themselves and the project to potential respondents as this may affect the response rate;

train just before the survey starts so trainees remember all the details;

don't select the field staff until after the training is completed;

check all the trainees in the field situation;

training on sensitivity of body measurements should be given;

there may be need to re-train the trainees if the survey is long term;

training must be given in the importance of respondent's confidentiality;

make training of supervisors a priority;

provide additional training for supervisors;

use role-playing.

Budgetary items for food consumption/anthropometric surveys (personnel and recruitment costs)

Salary (number of data collectors and supervisors), benefits - such as health, retirement (if relevant);

training and retraining (if needed) sessions. For trainers and trainees consider:

transportation;

housing, meals, per diem;

honorarium.

Equipment

Computer and computer supplies (disks, surge protector, back-up power source);

printer and printer supplies (toner, paper);

weight scales and height boards;

food models.

Office expenses

Office rental;

electricity and other utilities;

custodial and security services;

filing cabinets and other storage space;

office furniture;

telephone service;

mail service;

fax machine;

internet connection.

Field expenses

Field office (rental, furniture, supplies);

meal per diem;

transportation (public transportation fares, gasoline for motor vehicles, vehicle rental, vehicle insurance);

housing allowances.

Travel

Flight;

taxi/boat.

Others

Food scales;

watches, tape recorders and supplies (batteries, cassettes);

miscellaneous (backpacks, clipboards, notebooks, pens);

materials (flip charts, markers, notebooks)

When designing an FFQ, careful consideration should be given to the objective of the dietary assessment: is the aim to measure a few specific foods or nutrients or a comprehensive assessment of diet? A comprehensive assessment of diet is generally preferred as:

in general, one cannot anticipate all dietary factors that should be explored at the early stages of the study;

a highly restricted food list may not include an item that in retrospect, may be important;

total food intake, reflected as energy intake, may be related to disease outcome and as a result, confound the effects of specific nutrients or foods.

Furthermore, even if total energy is not associated with disease outcome, adjustment for total energy intake may increase the precision of specific nutrients. A full assessment of diet is advantageous also as data obtained may have long-term use, particularly in multi-centre studies and where opportunities to re-investigate the study population are limited.

However, a full assessment of diet becomes unnecessary and is replaced by short food frequency questionnaires when the aim is to measure intake of a nutrient (e.g. calcium) or specific dietary behaviour (e.g. consumption of fruits and vegetables) is of interest and the objective is to rank individuals according to levels of intake.

To develop a FFQ, a list of foods that contribute to at least 85 percent of the intake of the nutrients of interest for inclusion on the questionnaire needs to be established. This usually assesses food and drink intake over the previous twelve months.

DETERMINE FOODS CONTRIBUTING TO AT LEAST 85 PERCENT INTAKE OF THE MACRONUTRIENTS OF INTEREST

This can be done by collecting dietary data by any of the methods:

24-hour recalls;

food diaries;

weighed intake.

In the Caribbean because of practical issues such as literacy and unfamiliarity with food weighing, the 24 hour recall method may be preferred. Field workers need to undergo extensive training in how to obtain detailed 24-hour recalls (this usually takes a week for non nutrition trained personnel).

DETERMINE THE PORTION SIZES TO ASSESS QUANTITIES TO BE USED ON THE FFQ

The following could be used for this:

household units e.g. spoons;

natural units e.g. slices of bread;

food models;

photographs;

standard portions e.g. small, medium, large.

DETERMINE THE NUTRIENT COMPOSITION OF FOODS LISTED ON THE FFQ

This information can be obtained from:

food composition tables;

using values from other food composition table for similar foods (with caution);

calculating nutrient composition of recipes;

biochemical analysis.

A programme needs to be developed/accessed that will multiply the food frequency by the portion size by the nutrient composition of each food item listed on the FFQ (recipe or single food items).

DEVELOPING THE DRAFT FFQ

Foods contributing to at least 85 percent of the intake of the macronutrients and micronutrients of interest should be listed. For populations with less dietary diversity you could list all the foods (100 percent contributors). Foods are usually grouped into logical food groups such as vegetables, fruits and breads. Foods should be listed as single items and mixed dishes, but should not be double-counted. Frequencies of consumption are usually listed as several categories ranging from never to several times a day. FFQs usually ask 'How many times during the last 12 months did you eat?' Portion-size estimates will be listed in a separate column. Check questions can be added as well as additional information that may be useful for analysis e.g. if the person was following a weight-loss diet.

PILOTING THE FFQ

The FFQ will be drafted and then piloted to ensure feasible use and to obtain any omitted foods. Under each food group leave a few blank lines where any other foods in that category can be asked about e.g. "In addition to all those vegetables are there any other vegetables you ate during the last 12 months".

A manual must be written on how to administer FFQ. After pilot testing the manual should be updated including any changes in portion size estimates if necessary.

VALIDATING THE FFQ

Validation of the FFQ is carried out using another measure of food intake such as:

24-hour recall (multiple);

food diary;

weighed intake;

biochemical measurements using biomarkers in blood or urine.

Assess repeatability of FFQ

Consider the standardization of anthropometric measurements and dietary intake measurements (including measurement of inter-observer reliability);

repeat measurements using different field workers to establish variation between the interviewers;

repeat measurements using the same interviewer to assess reliability

WHAT IS QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?

Qualitative research can be viewed both as an approach and as a set of techniques for data collection. As an approach, qualitative research enables investigators to examine beliefs, perceptions and behaviours from local people's perspective. Qualitative methods can facilitate inquiry into sensitive issues, which are often difficult to investigate through standard survey methods. A qualitative research approach emphasizes four basic elements: (1) triangulation, (2) iteration, (3) flexibility, and (4) contextualization (Gittelsohn et al., 1994).

Triangulation

Triangualation can be defined broadly to be of three types:

1. data triangulation - comparing different data sources, i.e., from primary and secondary sources;

2. investigator triangulation - comparing the perspectives/interpretation of different investigators;

3. methodological triangulation - the use of multiple methods to study the same social phenomenon.

Use of multiple data sources, investigators, and methods provide the opportunity to better understand beliefs and behaviours. The assumption that different methods will necessarily lead to a convergence of findings and hence greater validity of data is erroneous (Mathison, 1988). Rather, the "value of triangulation lies in providing evidence - whether convergent, inconsistent, or contradictory - such that the researcher can construct good explanations of the social phenomena from which they arise". As an example, methodological triangulation in the area of infant-feeding might encompass focus groups with mothers, in-depth interviews with individual mothers who represent positive or negative cases and direct observation of infant feeding behavior.

Iteration

Iteration involves the use of earlier steps of data collection and analysis to inform later stages of data collection and analysis. Qualitative research does not, and should not follow a linear progression of planning, collection and analysis. Instead, researchers are encouraged to reflect continuously during data collection and analysis, and to modify approaches, and undertake new types of data collection as the study proceeds. Iteration helps researchers follow up on new and emerging findings, and can occur between methods of data collection, between stages of data collection, and between rounds of interviews with the same informant. In large field teams, it is important to build in regular meetings to review information collected thus far and decide on revised directions. From the infant-feeding example above, preliminary observations of infant-feeding behavior may reveal styles of feeding with the potential to influence infant nutritional status (e.g. passive or active). These findings could be followed up in in-depth interviews with mothers.

Flexibility

Flexibility refers to the qualitative researcher's ability to substantially modify data collection plans in mid-course, as part of the iterative process. If a particular method is found to be ineffective in generating the expected type of data, new methods may be adopted and/or developed.

Contextualization

Contextualization involves understanding the broader set of social, cultural, historical and economic factors that influence human beliefs and behavior. Qualitative research emphasizes understanding why people do the things that they do. In the area of food and nutrition, while qualitative research can contribute to understanding what people eat, it can make a stronger contribution to understanding why people eat the foods they do. People select, prepare, allocate, and consume foods for a wide variety of reasons that extend beyond availability and economics. This aspect is critical when exploring sensitive issues such as the inequitable distribution of nutritional health within households that is observed in some populations - and which has been attributed to differential valuation of some household members (e.g. men over women most commonly) over others.

The constructs described above reflect key differences between qualitative and quantitative approaches, but also emphasize their complementarity. Qualitative research excels at being part of the early, exploratory, hypothesis generating stages of a research endeavor. While quantitative research is very appropriately used to confirm and test hypotheses.

The discussion in Chapter 3 focuses on the use of qualitative research as formative research. Formative research is defined as information-gathering for the development, implementation and evaluation of intervention programmes (Gittelsohn et al., 1998, 1999). One of the major themes of formative research is cultural appropriateness (Resnicow et al. 1999). Formative research can be used to make intervention programmes both culturally and locally appropriate. It has its roots in applied anthropology, social marketing and educational psychology. Additionally, formative research can contribute to instrument development and for the formation of policy.

Formative research can include both qualitative and quantitative methods. It is the process by which researchers define and assess attributes of the community or target audience (Higgins et al., 1996). Formative assessment can also help facilitate relationships between researchers and target populations (Kumanyika et al., 2003; Gittelsohn et al., 1999; Gittelsohn et al., 1998) and can be applied at all levels of behavioural interventions, whether clinic-based (one-on-one and group interventions), school-based, community-based, or population-based, such as national media prevention campaigns (Gittelsohn et al., 1999; Higgins et al., 1996).

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH DESIGN AND DATA QUALITY

Qualitative research is characterized by emergent design. The flexible, iterative and exploratory nature of qualitative research ensures that no matter how carefully planned in advance, data collection must be open to exploring new directions. Nevertheless, there are key aspects of research design that characterize all or most qualitative studies. This includes issues of sampling, recruitment of informants, frequency of contact with each informant, the methodological mix, and other related issues.

Qualitative studies generally employ purposive sampling as the primary means of identifying respondents. Purposive sampling refers to the selection of informants based on specialized knowledge and experience. In the area of food and nutrition, most adult women are usually reasonably good informants, and so after selection based on some initial criteria (e.g., having small children, etc.), qualitative researchers will often try and interview/work with mothers or other caregivers who represent a range ages and experience in child-rearing.

Recruitment of respondents in a qualitative study is then linked to the sampling strategy being employed. However, a significant variation occurs in that in a qualitative study, most informants are interviewed multiple times. This permits the building of rapport and a social relationship of communication which is felt to enhance the flow of information.

A final aspect of qualitative research design is methodological triangulation. Multiple sources of information are felt to provide a better, more complete picture of the setting and topic under consideration. Thus, most qualitative studies use multiple forms of data gathering in order to provide those additional perspectives.

Analysis and reporting of qualitative data

Qualitative data analysis involves "the search for pattern in data and for ideas that help explain why those patterns are there in the first place" (Bernard, 2000). Most of the raw data produced by qualitative research is in the form of text, including transcripts of in-depth interviews and focus groups, descriptions from direct observations. This creates challenges for analysis and interpretation, as there are not standard approaches forworking with textual data in the same ways that exist for numeric data.

One principle of qualitative data analysis is clear: there must be continuous and ongoing engagement with the data. The qualitative researcher reviews transcripts (written up interviews, focus groups, observations) on a regular basis and may share findings with other data collectors, the lead researcher, or in some cases, with local informants (which Bernard refers to as "a constant validity check") (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

Qualitative data analysis can take one of two main strategies: categorizing or contextualizing. Categorizing strategies for qualitative data analysis involve the cutting and reorganizing of text so that similar items are grouped together (the editing approach). Software programmes such as N6, NVIVO and others have been developed to streamline the process. A related categorizing strategy involves the use of codes and coding manuals, where sections of text are assigned one or more codes to aid in later manipulation, organization and retrieval.

Contextualizing strategies for qualitative data analysis involve searching for information in texts that fit a broad framework. So for example, an examination of chronic disease might explore the perceived causes of the disease, who is affected by it, what is done about the problem and so forth. The write-up of qualitative data can take many formats: a formal report, a descriptive monograph (sometimes in the form of ethnography), articles for publication, website brief reports and so on. Within each of these formats, data may be presented in multiple ways, including the use of quotes, tables, matrices, maps and diagrams, taxonomies and decision trees and conceptual models (see Miles and Huberman, 1994 as an excellent resource on forms of presentation)

One of the primary means of disseminating the results of the study will be in the form of a report. Some key components of the report are suggested below.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This is a stand-alone executive summary for decision makers that highlights key issues, policy and programmatic implications, and suggests strategies.

In the Barbados Food consumption and Anthropometric Study the executive summary was constructed as a "Tool for Decision-makers" and was used as the basis for a two-day seminar to discuss the survey findings and the implications. The Summary was used as a stand alone document which provided a brief overview of the methods, summarized the main findings and presented some key policy and programme issues for further research/intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Be sure to acknowledge funders, study participants, etc.

INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

The literature review is frequently minimal in a report. However, sufficient review is required to identify gaps or biases in existing knowledge and to establish the need for the work.

GOALS/OBJECTIVES/RESEARCH QUESTIONS

This may include some description of the evolution of the research question(s), particularly the qualitative research questions.

ROLE OF THE RESEARCHER(S)

It is important to position the research within a particular historical and locally specific time and place. For the qualitative write-up, this may include disclosure by the author of his/her biases, values and context that may have shaped the report/narrative.

METHODS OR PROCEDURES

This section will include a brief description of the field site(s)/setting, sampling procedures (along with a table describing the samples), phases of the research (Plan of Work), short descriptions of qualitative methods and the process of developing the FFQ instrument, components of the research (instruments and techniques), selection and training of data collectors, languages used, and how the data were managed and analysed.

RESULTS OR FINDINGS

Start with simpler forms of presentation;

Be selective;

Use quotes/charts/diagrams/models/tables;

Consider use of case studies;

Can include a detailed description of the setting;

Consider dividing into sections, by objective/goal;

Sections may begin with an illustrative quote.

DISCUSSION AND INTERPRETATION

This may include linkages with theory.

RECOMMENDATION AND CONCLUSIONS

Programmatic;

information dissemination;

research.

REFERENCES

APPENDICES

Data collection instruments;

glossary of local terms and their rough english equivalents;

detailed description of methods;

additional results, tables