Par Mohamed NEDHIF

Tunisie

Les ressources marines en Méditerranée font l'objet, depuis très longtemps, d'une exploitation souvent intensive.Les fonds chalutables des côtes Nord de la Méditerrané Occcidentale ont subi une surexploitation et la production semble être en stagnation sinon en baisse.

Comparées aux côtes Nord de la Méditerranée, celles de la Tunisie sont considérées comme encore relativement riches notamment en poisson pélagique dont la production touche seulement 25% environ des stocks exploitables estimés è140.000T.par contre, la production de poisson de fond est de l'ordre de 60,000 T provenant essentiellment des zones Sud et Sud-Est qui enregistrent une surexploitation des potentialités qui a atteint, en 1986,120%.

Ainsi, l'augmentation de l'effort de pêche pourrait poser le problème majeur l'évolution des stocks de poisson existants et affecterait l'équilibre entre l'exploitation des stocks et leur renouvellement.

Prallèlement à la pêche, la Tunisie dispose de grandes potentialités pour dèvelopper l'acquaculture que est devenue dans le monde entier une nécéssité pour accroître la production de la matièe vivante marine.

ANNEXE 1

Modalités de création des projets d'aquaculture

| { | Demande | |||

| Demande de concession | ||||

| Avant projet | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

| C G P + Min Equipement | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

| Accord de principe pour l'exploitation d'une concession | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

| Demande de bénéfice des avantages de la loi 88-18 (Demande + Etude technico-économique de faisabilité + source de financement) | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

Agence de Promotion des Investissements Agricoles. <=> Comité d'Octroi d'Avantages - Min Agriculture - Min Finances - Banques Centrale de Tunisie - La profession | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

| Octroi : Décision d'Octroi d'Avantages | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

| Etude d'avant projet d'exécution | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

Etablissement contrat avec banques + Etablissement contrat location concession avec Ministère des Domaines de l'Etat | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

| Réalisation | ||||

• Les potentialités aquacoles

En Tunisie, de nombreux lacs qui sont de véritables mers intérieures tels que le lac de Biban, le lac Menzel Jemil, la mer de Boughrara, ainsi que des sites côtiers sont propices à l'implantation de fermes aquacoles.

A ces sites naturels s'ajoutent les barrages et les lacs collinaires qu'il est impératif d'exploiter pour le développement de l'aquaculture d'eau douce (mulet, carpe tilapia, anguille…).

Ainsi, environ 80.000 ha de plans d'eau saumâtre ou douce, peuvent être exploités en totalité ou en partie pour l'aquaculture.

Paralèllement à ce potentiel naturel, la Tunisie dispose de :

- Une cêté relativement salubre

- Une climat favorable : température, salinité, ensoleillement

- Une main-d'oeuvre qualifiée et disponible

• Place de l'aquaculture dand le VIII ème-plan (92–96)

Le VIII ème plan (92–96),qui accorde une place significative à l'aquaculture, prévoit d'atteindre une production annuelle de l'ordre de 3000 tonnes à l'horizon 1996.

Pour atteindre les objectifs du plan, toute une politique de privatisation a été mise en place. Elle se base sur une panoplie d'incitations financières et fiscales formant un cadre juridique privilègié, particulièrement pour la promotion de sociétés mixtes.

• Cadre Juridique Privilègié pour l'investissement dans l'aquaculture

La pêche et notamment l'aquaculture sont considérées comme activités prioritaires à encourager pour assurer la sécurité alimentaire et améliorer la balance de paiement par l'accroissement des exportations.

Dans ce cadre elles bénéficient d'importants avantages introduits par le Code des Investissements Agricoles et de Pêche (loi 88–18 du 2 avril 1988).

Ces avantages qui sont modulés en fonction du profil du promoteur, de l'activité envisagée et des lieux d'implantation du projet, peuvent être résumés comme suit:

Avantages Financiers

Bonification des taux d'intérêt: 4 points ou 5 points pour les projets réalisés dans les zones dont les ressources sont insuffisamment exploitées (Z.R.I.E).

Subvention d'investissement pour les petits projets et moyens projets dits de catégorie «B» qui est égale à 15% de l'investissement et de 20% pour les ZRIE.

Dotation remboursable (DR) pour parfaire l'autofinancement:

- Projets «B» (jeunes ou technicien): 80% de l'autofinancement qui est fixé par la loi à 10% de l'investissment.

- Projets «C» - jeunes ou techniciens: 80% de l'autofinancement.

- Autres: 50% de l'autofinancement qui est fixé à 30% de l'investissement.

Dotation de participation au capital pour techniciens gestionnaires (< 50.000 Dt).

AVANTAGES FISCAUX:

| AVANTAGES | CONDITION | ||

| Dégrèvement des revenus ou bénéfices réinvestis dans l'agriculture et la pêche. | Dans la limite de 70% des bénéfices et revenus réinvestis. | ||

| Dégrèvement des revenus ou bénéfices réinvestis dans l'agriculture et la pêche. | Dans la limite de 70% des bénéfices et revenus réinvestis. | ||

| Réduction des droits de douane au minimum légal et suspension des taxes sur la valeur ajoutée. | Pour l'importation des équipements non fabriqués localement. | ||

| Suspension des taxes sur la valeur ajoutée | Pour les biens d'équipement fabriqués localement. | ||

| Exonération de l'impôt sur les revenus des. valeurs mobilières. | Au titre des bénéfices distribués et parts d'intérêts n'excédant pas annuellement 10% de la valeur nominale des titres pendant 5 années consécutives à partir e la lère année bénéficiaire. | ||

| Exonération de l'impôt sur les bénéfices des sociétés. | Pendant 5 années complémentaires pour les projets agricoles réalisés dans les régions aux conditions climatiques difficiles et les projets de pêche réalisés dans les gouvernorats cêtiers dont les ressources de pêche sont insuffisamment exploitées. | ||

| Prise en charge totale par l'Etat des contributions patronales au régime de sécurité sociale pendant les cinq premières années d'activité effective. | Pour les projets réalisés dand les régions aux conditions climatiques difficiles et les gouvernorats côtiers dont les ressources de pêche sont insuffisamment exploitées. | ||

CONCLUSION:

Ces incitations ont permis de créer une tradition aquacole. Des promoteurs des domaines industriel et touristique ont investi dans l'aquaculture.

Egalement des petits projets sont réalisés par des techniciens et des jeunes promoteurs.

Toutefois la production aquacole reste en deç à des prévisions.

Ainsi un ensemble d'actions et de mesures d'encrouagement doivent être envisagées à savoir :

- Approfondir les études relatives aux choix des sites.

- Revoir les facteurs de production.

- Rechercher de nouveaux marchés.

C'est l'objet du plan directeur de l'aquaculture qui est en cours d'élaboration.

REPUBLIC OF TUNISIA

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE

AGRICULTURAL INVESTMENTS PROMOTION AGENCY

Guide

For Foreign Companies Participation

«Agricultural and Fishery Investments Code»

(Law № 88–18 of 2 April 1988)

PROCEDURES AND CONDITIONS OF UNDERTAKING JOINT-VENTURES

Prior licence from the Ministry of Agriculture, subsequent to presentation of :

- Status draft.

- Land Renting contract draft for 25 years renewable.

- The amount of the company's authorized capital.

- List of shareholders, indicating their nationality, and enveryone's share (the participation of foreign partners can reach 50 percent of authorized capital).

- The amount of investments to be made.

- An outline of the proposed project.

Final licence subsequent to presentation of :

- Status of the company.

- Land Renting contract.

- Technical and economic study approved by the Agricultural Investments Promotion Agency (APIA), indicating a detailed program of all actions to be undertaken toward the implementation of the project and the financing scheme.

- List of members of the Board indicating their nationality.

AGRICULTURAL INVESTMENTS PROMOTION AGENCY

(APIA)

62, Rue Alain Savary - 1003 Tunis Khadra - Tél.: 288.400 / 288.091

Télex : 14.280 - Fax : 782.353

| FINANCIAL BENEFITS | ||||||||

| BENEFITS | CONDITIONS | |||||||

| Guarantee of transfer of invested capital in hard currency and income thereon. | For non-résident investors. | |||||||

| Facilities of setting in Tunisia. | For non-resident investors. | |||||||

| Assumption by the state of costs of project studies. | Up to maximum of 5000 D. | |||||||

| Bonus of Band loan interest rates. | Preferential rates in comparison with other non-agricultural sectors and an additional, bonus for disadvantaged regions and priority sectors. | |||||||

| Granting of a subsidy of 5 percent of the total amount of investments. | For projects undertaken in the disadvant aged regions (Governorates of Gabes, Mednine, Tataouine, Gafsa, Tozeur and Kebili) and coastal Governorates whose sea resources are under-exploited (Bizerte, Beja, Jendouba and Kelibia). | |||||||

| Granting of a subsidy for the purchase of agricultural equipment necessary for the development of the project. | 10 Percent of the total cost of equipment. | |||||||

| Total or partial assumption by the State of the costs of the training of personnel. | For projects bringing in technological contribution. | |||||||

| Granting of an endowment repayable to managers among technicians in respect to their participation in these companies' capital. | This endowment is repayable over a period of 10 years, with a 3 years grace and an interest rate of 6 percent, and represents 80 percent of the 10 percent of the capital, with a maximum of 50.000 D. | |||||||

| TAX BENEFITS | ||||||||

| BENEFITS | CONDITIONS | |||||||

| Tax exemption for income or profits reinvested in agriculture or fishery. | Within the limit of 70 percent of the companies' profits. | |||||||

| A fixed registration fee of the instruments of incorporation at the enterprise, as well as instruments pertaining to capital increase and modification of the status. | For a period of 10 years. | |||||||

| Reduction of customs duties and supension of turnover taxes. | For the import of equipment not locally manufactured. | |||||||

| Tax exemption for industrial and commercial profits or for companies' profits | During the first 10 years, and payment of tax at the reduced rate of 10 percent from the 11th to the 15th year. | |||||||

| Suspension of turnover taxes. | For capital goods locally manufactured. | |||||||

| Tax exemption for incomes from transferable securities | In respect to distributed profits and interest shares not exceeding annually 10 percent of the nominal value of the shares during 5 consecutive years from the first year in which profits are made. | |||||||

| Tax exemption for the promoters' dues. | For projects bringing in technological contribution. | |||||||

| Tax exemption for industrial and commercial profits or for companies' profits. | For 5 additional years for agricultural projects undertaken in disadvantaged in regions and fishery projects undertaken coastal Governorates whose sea resources are under-exploited. | |||||||

Par Dr James F MUIR

Scotland

1- Introduction

The purpose of the presentation; although not in the Mediterranean, an example of a medium scale ‘mixed economy’, relatively unstructured industry development during a period of rapid growth and high expectation. A varied pattern of investment, some of which have shown to be effective, others less so, the aim here to review these, and hopefully, although each industry and its institutions are unique to their own areas, to indicate any lessons which might be learnt…

History, pattern of investment, structure of industry, size of industry; eg Scottish salmon about 40,000t, worth some '£100–120 million at farm-gate; trout industry some 5,000, worth some £75 million at the farm-gate; the other sectors perhaps £2–£5 million in direct sales/earnings. Representing in crude terms a capital investment of perhaps £100–150 million, with an annual ‘working capital’ spend of perhaps £50 million.

The role of investment in growth

Possible areas of distortion-eg has investment characteristics moved the industry away from what might be considered an‘ideal’ form?

2- Investment requirements

Characteristic businesses:

- Trout; ponds and cages

- salmon smolt; simple/complex

- salmon ongrowing; tank and cage

- specialist; eels, seabass, tilapia, Mussels, cysters, scallops

- leisure; put and take, visitor centres, etc

Capital and operating requirements:

Cash flow characteristics

Risk and Loss

3- Patterns of investment

Quite unlike Norway, Canada, etc; partly societal; ownership, assets, attitudes to risk-taking; Two main categories;

- individuals - small to medium scale; fishermen/small farmers, small business operators, family, landed estate resource owners

- companies; medium to large sized companies; food/agro-industry, technical/engineering No co-operative, but possible note a third category the variously funded R and D establishments -

Two main approaches:

- self-financed, with some marginal assistance

- conventionally financed, eg through equity and debt

4- The financing system:

Project investment

Equity/own funds

Grand assistance - HIDB/HIE, SDA/SE/LECs, the IDP, ADP system

Bank borrowings, loans and overdrafts - UK and Norwegian banks

Venture capital, BES

Other sources; taxation, site value/growers contracts, trade customers/cashflow management, lease

finance

Infrastructure investment

R and D establishments not directly funded eg from DAFS (though a proposal once existed), but

through eg SFIA (WFA), HIDB (HIE) - sometimes distinctions between R & D and production could

become rather blurred - see later

5- Performance and problems

Has the system worked well?

- the industry has developped and grown

- it has not been easy for smaller producers to capitalise their knowledge, resources, etc

- there is a risk of the industry becoming too heavily dominated by large companies;

- there are problems of ‘short - termism’ eg with the banks

Overall rate of failure? rates of growth? Restructuring and ‘sunk capital’? overall perceptions of strength and security?

Has there been sufficient enrichment during early higher-return years to provide a stable investment base for the future?

Basic cashflow and risk profile of long-cycle production; less so with trout, to some extent smolt

production; leisure and other activites far less so;

Grown Commission/site rental philosophy; Values of sites; but not realisable

Risk coverage - one off vs recurrent; self-insurance

Security on stock

Investment risk coverage

DAFS/EC HIE in past - criteria for investment support/approval

6- Implications/ideas for elsewhere?

Recognising different cultural, institutional characteristics

The value of the ‘learning curve’ - both by producers and by financial institutions;

The need for properly developed business plans with careful assessments of key variable, sensitivities

For technology-based projects, the need for a sound technology assessment approach

The importance of human resources; skills, management capacity

The importance of effective insurance

The need for specific targeted ‘risk-reducing’ development programmes

If small farmers are to be encouraged, the need for targeted financial support

The need for mechanisms to share investment risk

Rate of Growth

- Scottish salmon industry :

| Year | Production | % increase |

| 1981 | 1133 | |

| 1982 | 2152 | 89.9 |

| 1983 | 2536 | 17.8 |

| 1984 | 3912 | 54.3 |

| 1985 | 6921 | 76.9 |

| 1986 | 10338 | 49.4 |

| 1987 | 14000 | 35.4 |

| 1988 | 17600 | 25.7 |

| 1989 | 28550 | 62.2 |

| 1990 | 32350 | 13.3 |

| 1991 | ~ 41000 | 27.0 |

Overall growth rate : 1981–1990 45.12%.

Farmed salmon production 1980–1988

Norway, Scotland & Ireland

Crannag trout Company

target production 2000 pa

Scottish salmon industry

| Hatcheries | 1998 | 1990 |

| No. of scottish companies | 90 | 75 |

| No. of production sites | 176 | 142 |

| Production (million) | 225 | 202 |

| (capacity (1000m3) | 276.5 | 321.4 |

| % cage-based. | 85.7 | 58.4 |

| Ongrowing | 1988 | 1990 |

| No. of companies | 153 | 171 |

| No of sites | 258 | 345 (298) |

| Total voluma(milion m3) | 4.3 | 5.5 |

| % cage-based | 98.4 | 99.0 |

| Production, t. | 17,951 | 32,350 |

| Avge production /site | 69 | 108 |

| Avge production /1000 m3 | 4.17 | 5.88 |

| Avge production /company | 117 | 189 |

| Employment | 1988 | 1990 |

| Full time | 1335 | 1387 |

| Part time | 448 | 401 |

| Total | 1783 | 1788 |

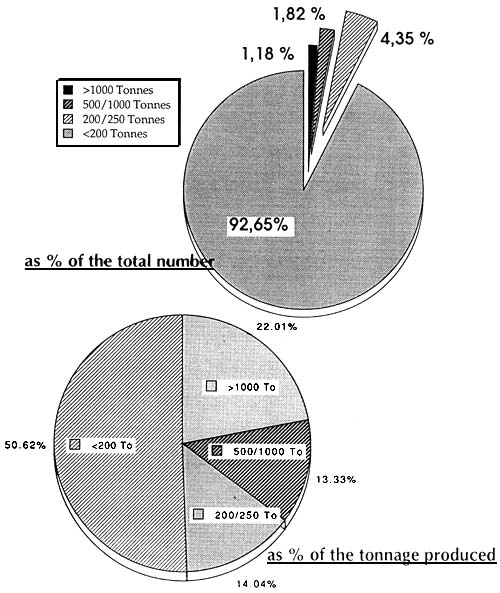

The proportion of farms of various production levels (tonnes/year)

The proportion of Scottish salmon production by compagny size (tonnes/year)

Scottish Fish Farms

By Mr.S.R. STEIN

APRECUÇU DES LÉHISLATIONS NATIONALES ET DES ACCORDS INTERNATIONAUX AYANT TRAIT à LA FUTURE COOPÉRATION DANS LA RÉ: INTERVENTION SUR LES LOIS ACTUELLES SUR L'AQUACULTURE ET SUR LE CONTROLE DE QUALITÉ.

1- LES LOIS NATIONALES SUR L'AQUACULTURE

1.1 Généralités

A la différence du régime juridique concernant les pêches maritimes qui a fait l'objet d'une attention consideérable depuis 1945, le régime juridique relatif à l'aquaculture a plutôt été négligé. Rare sont à l'heure actuelle les pays, et en particulier les pays en voie de développement, qui ont promulgué une législation appropriée pour régir le secteur de l'aquaculture. Peu de lois ou de réglements sont conçus à dessein pour protéger ou permettre cette activité. Il existe généralement des dispositions qui y sont applicables dans des lois et réglements régissant les différents usages de l'eau et de la terre, la protection de l'environnement et enfin et surtout la pèche. Et même dans le cadre de la législation sur la pêche, l'aquaculture est souvent une activité halieutique au même titre que la pêche maritime ou intérieure (pêche de capture, sportive,…) et ne fait guère l'objet de mesures paticulières. Ainsi l'aquaculteur est souvent confronté à un réseau complexe de lois et règlements traitant du régime foncier, de l'utilisation de l'eau, de la protection de l'environnement, de la prévention de la pollution, de la santé publique et des pêches en général. Il s'ensuit que la confustion. les litiges et les chevauchements sont de rè. Mais il s'ensuit également qu'un régime particulier pour l'aquaculture doit garantir que soient couverts les besoins des aquiculteurs et les objectifs du Gouvernement, mais aussi que soient intégrées comme il convient les lois pertinentes existantes ou à venir. considérée dans cette optique, la législation peut être un outil essentiel pour gérer de façon rationnelle les opérations d'aquaculture et leur milieu naturel.

Quoiqu'il en soit, lors, d'une étude relative au cadre juridique régissant les activités d'aquaculture, trois catégories de pays ont été identifiés:

pays possédant une législation particulière s'appliquant expressément à l'aquaculture (Canada, USA, Nouvelle Zé, France, UK);

pays où il existe quelques textes législatifs traitant d'un certain type d'aquaculture ou d'un aspect particulier de cette activité, souvent en fonction d'un besoin particulier (Equateur loi sur l'élevage des crevettes en zones côtières et l'accès à ce domaine public par le biais de concessions);

pays où il existe une loi-cadre comprenant soit quelques dispositions générales soit une clause habilitant l'autorité compétente de préparer des règlements pour l'exercice de l'aquaculture.

1.2 Quel est le champ d'application de ces lois et leur portée c.a.d. quel est le type d'activité que la loi/règlement, bref, l'acte législatif est destiné à réglementer.

Fort peu de pays prévoient un régime unique et général. La plupart des Etats ont en effet éprouvé la nécessité de ne ré que certains types d'activités aquacoles et d'accorder un régime différencié en fonction du statut juridique des eaux (publique versus privé) {c'est le cas de la République de corée, la législation s'applique des eaux du domaine public et aux eaux du domaine privéformant un tout avec les eaux du domaine public qui leur sont reliées, et en partie le cas de la France, les dispostitions relatives à la pisciulture concernent tous les plans d'eau douce du domaine public et les eaux du domaine privé qui leur sont reliées, tandis le Décret sur la mariculture est applicable à toute exploitation dans l'eau de mer (qui relève du domaine public) et sur des terrains privés si l'exploitation nécessite le prélé vement d'eau de mer. Souvent dans ces, l'autorisation administrative semble couvrir à la fois la création de l'établissement et l'octroi d'une portion de plan d'eau à utiliser pour l'aquaculture} ou en fonction de la nature des eaux (eaux douces versus eaux maritimes). En effet, dans plusieurs pays tels que Hong Kong, Singapour, Espagne la loi/le règlement traitant de l'aquaculture ne's applique qu'aux eaux maritimes, tandis que dans d'autres cas seules sont concerneées les installations d'aquaculture créées en eau douce {voir la France déjà mentionnée et la Nouvelle Zélande}. CEPENDANT, certains Etats ont promulgué une législaion qui ne s'insère nettement dans aucune des catégories sus-citées.{A titre d'exemple peuvent être cités l'Equateur où la loi principale règlementant la création de stations aquacoles est en fait applicable uniquement aux «zones de bahias y playas» ou la Norvège où la loi traitant de l'aquaculture a pour particularité d'être applicable à «l'élevage en eau douce, en eau saumatre ou dans les eaux salées», qu'il s'agisse du domaine public ou de propriété privée.}

1.3 Une caractéristique commune à plusieurs pays

Bien que le champ d'application ou la porté la loi-cadre puissent varier d'un pays à l'autre, on peut néanmoins observer que dans la plupart des pays une procédure administrative fondée sur l'approbation préalable de l'administration pour la création d'installations d'aquaculture est prévue. Cette autorisation peut être accordée par différentes autorités et peut porter des appellations différentes (autorisation, licence, permis , enregistrement, bail et concession) mais il demeure que tous les pays que l'on a pu examiner exigent l'agrément d'un organisme public compétent. Celle-ci permet aux autorités compétentes d'intervenir au niveau de l'aménagement et du développement de l'aquacultue. En effet, un régime d'autorisation semble comporter plusieurs avantages : il constitue un instrument privilègié d'une politique de gestion des ressources en permettant de régler l'afflux des aquiculteurs dans un périmètre géographique déterminé; il fournit une base sérieuse pour la collecte d'informations et létablissement de statistiques sur les activités des stations aquacoles (espèces élevées, équipement, méthodes utilisées, etc.); il permet de soumettre l'aquiculteur, au moyen des modalités et conditions attachées à l'autorisation, à certaines obligations relatives à la conduite et à la gestion de la station aquacole, à la conservation de la qualité des eaux, à la prévention de la maladie des animaux, etc…,; il peut constituer une source de revenu pour l'East à travers le paiement d'une redevance. Ordinairement, l autorisation (ce terme étant pris dans son sens le plus large) accordée est un permis d'élevage d'espèces aquatiques (faune ou flore). Il existe habituellement un système global de délivrance des permis, quelle que soit l'espèce dont l'élevage est prévu ou le milieu dans lequel il est prévu. Toutefois dans certains cas, des licences ou autorisations spéciales sont nécessaires. {Aux Philippines, outre la licence normale, une licence spéciale est nécessaire pour construire ou exploiter un enclos á poisson et pour sa part la France exige une autorisation spéciale pour les installations d'élevage de saumon, que cette activité ait lieu dans des eaux du domaine public ou du domaine privé, en eau de mer ou en eau douce.} En outre il convient d'observer que l'autorisation de créer une station aquacole peut être liée à l'obtention d'autres types d'autorisations pour l'accés à l'eau et/ou aux terres, pour décharger, les effluents, etc… Exceptionnellement, l'instrument légal régissant l'aquaculture en fait état explicitement.

1.3.1 Quelles sont les obligations préalables à l'obtention de l'autorisation?

De manière générale, il existe l'obligation de fournir des documents et des informations sur l'activité envisagée: {ces documents et indications peuvent porter sur l'identité du demandeur, l'espèce qu'il est prévu d'élever, plans indiquant l'emplacement, les ouvrages de prélèvement et d'évacuation des eaux, l'origine de l'eau à utiliser, méthodes d'élevage,} …en résumé, nous pouvons dire que les demandeurs doivent habituellement fournir trois types de documents et d'informations:

- informations administratives et économiques : le nom et le statut juridique du requérant, ses moyens financiers, tout titre pertinent etc;

- information géographiques : notamment la carte de la zone prévue avec, dans certains cas, un plan détaillé des locaux et des installations qui y seront construites;

- informations techniques : les espèces à élever, les méthodes à adopter pour exploiter la station aquacole, l'objectif de production, les aliments utilisés, et encore exceptionnellement une étude d'impact sur l'environnement de l'activité aquacoleentreprise, etc…

En outre, les demandeurs doivent parfois satifaire à certaines conditions de citoyenneté (entr'autre parce que l'aquaculture implique une occupation prolongée de l'eau et de la terre), tandis que, dans certains pays, souvent les pays développés, certaines qualifications professionnelles peuvent être exigées.

1.3.2 Conditions et modalités attachées aux autorisations

Comme pour toute autre activité économique, des conditions et modalités sont attachées aux autorisations. Habituellement on y trouve toujours des conditions relatives à la durée de l'autorisation, au paiement et au renouvellement de celle-ci. Le Service juridique dispose de peu d'information sur les redevances appliquées. Toutefois, parmi les pays analysés, on a pu constater que les redevances étaient payées sur une base annuelle même si l'autorisation est accordée pour plusieurs années, que le type d'aquaculture exercé peut être déterminant, tout comme la superficie de l'eau ou de terres en cas de concessions.

En outre, l'autorisation est accompanée de conditions et des modalités particulières. Celles-ci peuvent porter sur :

- la libre circulation des espèces aquacoles;

- l'utilisation ultérieure de lal zone autorisée pour l'aquaculture;

- les informations périodiques et l'accès en permanence à l'installation à fournir;

- la date limite de démarrage des activités aquacoles;

- le marquage, la délimitation et l'éclairage de la station aquacole;

- le contrôle de la qualité des eaux;

- la prévention des maladies des espèces élevées;

- etc.

A ce sujet, on est frappé par la diversité des options dont disposent les Gouvernements.

2 - LE CONTROLE DE LA QUALITE DES EAUX

L'aquaculture peut avoir un impact écologique sur les cours d'eau, les lacs et les zones côtières et la pollution de l'eau fait peser une lourde menace sur l'aquaculture.

2.1 Le contrôle de l'aquiculteur/pollueur

Quelques observations :

Rares sont les législations qui traitent expressément du déversement d'eaux usées ou du rejet de substances polluantes par les stations aquacoles;

Il existe quelques dispositions communes dans de nombreux pays, qui stipulent entr'autres que :

- le déversement de tout polluant doit faire l'objet d'une autorisation préalable octroyée par une autorité administrative. Soit celle-ci est incorporée dans l'octroi du permis ou de la concession régissant l'utilisation de l'eau, soit accordée séparément dans le cadre d'une loi sur la protection des eaux ou de l'environnement en général;

- le particulier, de manière générale, a l'obligation légale de prendre des mesures anti-pollution appropriées souvent à ses propres frais en vertu d'une condition ou d'une modalité incluse à l'autorisation générale, de l'utilisation des eaux et rarement en vertu de l'autorisation de créer une station aquacole. Dans ce dernier cas, le pisciculteur a notamment l'obligation de mettre en place des installations ou du matériel appropriés pour restaurer la qualité des eaux usées qui sont déversées {C'est le cas de EI Salvador, la Nouvelle Zélande, la France,…};

les autorités de contrôle et d'cotroi des autorisations sus-citées sont rarement celles qui octroient l'autorisation relative à l'établissement de la station aquacole. Quoiqu'il en soit, la question déterminante est de savoir quel est le moyen le plus efficace pour contraindre l'aquiculture de protéger, préserver et respecter l'environnement sans le mettre en difficulté quant à l'exercice de son activité, sans lui faire subir des coûts financiers considérables.

2.2 La protection de la qualité des eaux aux fins de l'aquaculture

De maniére générale, on n'accorde peu d'attention à l'importance de la qualité de l'eau et à sa protection aux fins de l'aquaculture et l'on en droit de se damander si les pays ont conscience de la vulnérabilité de l'aquaculture à la pollution. Que trouve-t-on comme dispositions? Ici encore, les lois sur la protection de l'environnement, les lois relatives á l'eau et les lois sur la conservation et la protection des ressources naturelles traitent surtout de la lutte contre la pollution. Et de ce fait, rares sont les pays qui établissent une distinction entre les eaux intérieures et les eaux marines.

Toutefois, nous pouvons trouver des mesures spécifiques en la matière, (qui, notons le concernent fréquemment la culture d'espèces aquatiques dans les eaux côtières, marines, ou saumâtres), telle que (la liste n'est point exhaustive!);

- l'imposition d'une zone de «sécurité» autour d'une station aquacole {par exemple, l'Equateur : afin de protéger les eaux contre les pesticides et d'autres substances nuisibles utilisées en agriculture et en même temps de protéger les exploitations agricoles contre les effets du sel, il faut prévoir lors de la construction des bassins à poissons et des centres d'alevinage une bande de sécurité d'au moins 200 m de large à partir de la limite de l'exploitation agricole};

- l'interdiction d'établir des stations aquacoles en dehors des «zones maritimes protégées» où l'on accorde une attention particulière à la conservation et à l'utilisation de l'environnement sur le littoral avec par exemple la lutte contre les maladies ou contre l'introduction d'espèces exotiques;

- le respect de normes de qualité pour un type d'aquaculture {Directives des CEE qui concernent la culture des salmonidés et les cyprinidés, ou encore, au Mexique, en France, aux Philippines: une attention particulière existe pour la qualitédes eaux la conchyliculture};

- l'interdiction générale de déversement, sans traitements appropriés, dans la mer, directement ou indirectement, d'eaux ou déchets qui pourraient contaminer les zones qui présentent un intérêt particulier pour la mariculture {c'est le cas de l'Espagne};

- l'établissement de critères et de paramètres admissibles relatifs à la qualité des eaux utilisées dans les différentes activités d'aquaculture c.a.d. il s'agit d'exigences auxquelles un milieu aquatique ou partie d'un milieu aquatique doit satisfaire afin qu'une telle activité d'aquaculture puisse y être exercée.

Il convient également de mentionner que toutes ces mesures précitées ont parfois tendance à allonger outre mesure la procédure administrative applicable pour obtenir les agréments nécessaires, et ne répondent pas toujours effectivement aux objectifs qui leur étaient assignés. Ceci est d'autant plus vrai qu'en matière de protection et conservation de l'environnement aquatique en général, l'on trouve souvent un «pachwork» de mesures qui ont été prises souvent sur une base «Ad Hoc» permettant de résoudre un problème récurrent.

De toute évidence, les activités d'aquacultures ne sont pas faciles à réglementer, non seulement à cause de leur diversité, mais aussi en raison de leur interdépendance avec d'autres aspects essentiels du systéme juridique, à savoir la lègislation relative au sol à l'eau.

3- LES ACCORDS INTERNATIONAUX QUI PRESENTENT UN INTERET POUR LA COOPERATION EN MATIERE D'AQUACULTURE

3.1 Introduction

A mon humble connaissance, il ne me semble pas exister à présent des accords internationaux ayant trait directement à l'aquaculture en générale et assurant une co-opération à ce sujet entre plusieurs pays.

Toutefois, le souci de protection des espaces littoraux et, entr'autres du méditerranéen, a incité certains pays par le biais de conventions internationales consacrées à la pollution, et plus particulièrement la pollution tellurique - c.a.d. toute pollution marine du continent - et pélagiques à prendre des mesures et à adopter des programmes afin d'éliminer ou de réduire la pollution. Habituellement ces conventions se réfèrent explicitement ou implicitement aux objectifs de qualité du milieu marin.

3.2 Les conventions relatives àla pollution tellurique

Les conventions relatives à la pollution tellurique, qui sans nul doute revêtent une importance particulière pour la mariculture, semblent identifier deux techniques principales de prévention et de lutte contre la pollution tellurique en fonction du milieu et du rejet de substances polluantes. Rares sont les conventions dont la cible est l'opération/l'activité polluante.

3.2.1 Réglementation de la qualitédu milieu (souvent par rapport àune substance polluante

Nous pouvons citer à ce propos les conventions et recommandations suivantes:

- La Convention de Paris du 2 juin 1984 pour la prévention de la pollution marine d'origine tellurique : les parties contractantes s'engagent à prendre des mesures de lutte contre la pollution tellurique parmi lesquelles des «règlements… spécifiques à la qualité de l'environnement» (art.4,&3).Dans la mise en oeuvre de leur politique les Etats doivent «prendre en considération la qualité … des eaux réceptrices» (art.6, c). Enfin, des accords spéciaux entre les parties contractantes sont prévus pouvant «entre autres, définir… les objectifs de qualité à atteindre»;

- le protocole d'Athènes relatif à la protection de la mer M éditerranée contre la pollution d'origine tellurique, du 16 mai 1980: il stipule que les Parties élaborent et adoptent des normes et des critères communs concernant «notamment la qualité des eaux de mer utilisées à des fins particulières nécessaires pour la protection de la santé humaine, des ressources biologiques et des écosystèmes…» (Art. 7, c)

- par la Recommandation des Parties contractantes au Protocole d'Athénes sur la qualité du milieu pour les eaux conchylicoles (5èunion mars 1998) des critères ont été adoptés;

L'action des Communautés Européennes en matière de protection de l'environnement et protection de la mer n'est pas non plus négligeable. Depuis 1973, la lutte et la prévention entre la pollution marine sont devenus progressivement des sujets prioritaires. En ce qui concerne la pollution tellurique, un véritable système normatif intra-communautaire a été, ce par voie de directives. Celles-ci fixent les objectifs de qualité du milieu marin en fonction de l'usage ou de la vocation de ce milieu, en l'occurence la baignade (Directive du conseil/160/CEE) et la conchyliculture (Directive du Conseil 79/923/CEE). En outre, la CEE participe à la collaboration internationale règionale en étant signataire de la Convention de Paris (Décision Conseil 75/437/CEE) et du Protocole d'Athènes (Décision du Conseil du 26/2/1983).

3.3 Réglementation du rejet de substances polluantes

Les initiatives internationales et communautaires sont assez nombreuses. Il s'agit donc de normes qui permettent de contrôler le rejet lui-même de substances polluantes. Ces mesures de contrôle peuvent se distinguer en deux groupes:

La Convention de Paris et le Protocole d'Athènes prévoient un classement des subtances polluantes susceptibles d'être déversées dans le milieu marin en fonction de leur nocivité, sur la base des critères de toxicité, de persistance et de bioaccumulation. Deux listes sont établies (noires et grises) et détermniner toutes les mesures de lutte contre la pollution et les Parties Contractantes devraient adopter et harmoniser. N'étant pas expert scientifique en aquaculture, il me fût difficile d'identifier parmi les substances nocives énoncées celles que l'aquaculture est susceptible de déverser.

Les Conventions précitées imposent l'obligation de l'autorisation préalable de rejet que sur la liste grise (exemple, zinc, cuivre, nickel, arsenic,…) et prévoient parmi les mesures à prendre pour les substances les plus nocives des normes de rejet et des normes d'émission la convention de Paris art. 4 al.3, Protocole d'Athènes, art. 5, al.3)

3.3.1 Les conventions relatives à la pollution pelagique

Il s'agit des conventions relatives à la pollution maritime par oppostion à la pollution terrestre. Les conventions principales en question concernent la pollution par les navires convention MARPOL 73/78), La pollution par immersion (le Protocole de Barcelone de 1976) et pollution découlant de l'exploitation du plateau continental. Bien que ces conventions peuvent éventuellement présenter un certain intérêt pour l'exercice de l'aquaculture, faute de temps elles n'ont pu être étudiées.

DOMAINES DE COOPERATION POSSIBLE EN AQUACULTURE

Les domaines dans lesquels une co-opération peut être encouragée sont les suivants:

au niveau de l'échange d'informations et de statistiques (espèces élevées, techniques utilisées, équipement, installation, composition de l'alimentation artificielles

au niveau du contenu des études d'impact sur l'environnement que les aquaculteurs désireux d'établier seront de plus en plus chargés de fournir;

au niveau des techniques de contrôle de la qualité des eaux: «pollution standards, paramètres, antillonnage, etc…);

l'élaboration d'un code de conduite sur la gestion des stations aquacoles;

l'élaboration de «standards for environmental safeguards» :mesures harmonisés permettant de gérer l'aquaculteur/pollueur et l'aquaculteur/récepteur de pollution;

l'harmonisation des législations nationales traitant des sujets cités ci-dessus (études d'impact, rôle de la qualité des eaux, gestion rationnelle des stations aquacoles, etc…)

BY Mari Elisa VASCONCELOS

Portugal

INVESTMENT POLICY

The European Community financial aid to aquacultue development has been one of the main support lines of the structural fisheries policy. Since one of the measures foreseen by this policy is the adjustment of EC fleet's fishing efforts to the availability of fishery resources it is important that conditions are created to complement traditional fish production.

Hence, and widely speaking, aquaculture products may in the long term enable certain fish products to be gradually replaced. Such products may thus contribute to some kind of reduction of the adverse trade balance between the EC and its third countries trade partners.

The existing EC aid is completed by Council Regulation (EC) No. 4028/86 and 4042/89 and transposed to national legislation through Decree Law no. 399/87 of 31 December and Decree Law no. 441/91 of 16 November.

The sector's development policy is periodically defined by means of multiannual guidance programmes. with applications for financial aid being in line with the general guidelines.

The first programme ran from 1987 to 1991 and aimed at using the full potential of existing natural resources, and increasing production on the coastline and in inland waters. Consequently its guidelines are aimed at:

It must said that the aquaculture activity has little significance in the national economy compared to fisheries.

Until, now bivalve rearing has been predominant in salt and brackish waters of estuarine areas and coastal lagoons' extensive fish farming is equally important in these waters being generally pursues in estuaries where water renewal is secured by tidal movement. These units are often associated to salt production or result from its conversion.

In freshwater areas, intensive units have been established since the seventies, mainly for rearing trouts and, what is more important, fish farmers have been benefiting from aid through the dissemination of techniques that have proved to be efficient in State-owned units.

The new multianual guidance programme-MGP 1992/96 is aimed at creating conditions for:

This programme has for the first time provided projects in collective infrastructure (road networks, power supply, sewage structures), as well as for general infrastructure (development of waters circulation in lagoons and estuaries pilot units for juvenile breeding, with the necessary facilities for pre-juveniles and demonstration of different techniques).

MASTER PLANS

The Portuguese coastline has good environmental conditions for the development of marine rearing activities.

However, problems related to competition from other economic activities (such as those of touristic and industrial nature), town planning and restrictions placed by environment authorities have hindered an effective implantation of marine culture units.

With regard to the Environment sector, there is widespread concern for the influence of fish farming on water quality, its reflexes on the marine bird habitat and on the natural environment.

It can also be said that master plans for these regions often tend to give priority to the other activities that are likely to contribute more decisively to social and economic development. This short-term approach ends up by placing aquaculture development in second place.

Research and training are fundamental aspects for development of an aquaculture structure.

Several times of work have been developed in research, namely for the:

- increase in the survival rate of larvae and juveniles;

- preparation of feeds, particularly for larvae and juveniles;

- study of disease affecting species being reared with a view to preventing and treating them;

- study of new rearing systems, namely in floating structures;

- zootechnical improvement of reproducers.

Training activities have been developed both at academic level (universities) and at professional level.

There is a specialized data base at the National Fisheries Data Rank with information related to aquaculture units. It covers a number of elements, such as the description of the unit type, the system of operation, authorized species, legal states and everything related to the activity pursued and to levels of production.

Investments made have also been computerized so that eventually an idea can be made of their efficiency.

A survey of the situation has been made during the last two years by means of individual enquiries.

LEGAL AND REGULATORY ASPECTS

Marine culture is regulated by Decree Law a.261/89 of 17 August established the general principles governing the activity and by Administrative rules no.980-A, B and C/89 of 14 November ensuring administrative and technical regulations.

There is a special process for authorizing a unit to be established either of private property or in State-owned property. There are different requirements relating to local salubrity, non-collision with other local activities or with marine species natur5al banks, and the fact that they must not be a threat to navigation or be contrary to environment regulations.

Committees meet twice a year in order to assess all existing applications for the region. They include representatives from the Maritime Authority, the Administration, Research, Health and Environment authorities, administration of the territory concerned as well as municipal authorities. These representatives, with in their powers, give their opinion about specific projects and their viability, taking the site into account. A negative opinion from any of the representatives becomes binding.

The legal process for grading and operation license covers all the conditions for establishing the unit from restocking toe salubrity requirements. The process ends with the granting of a licence which is valid for 10 years and renewable for equal periods of time.

Different measures have been foreseen for the surveillance and monitoring of technical and salubrity conditions. These will be secured by different bodies according to specific objectives.

ECONOMIC ASPECTS

In inland waters, the domestic market absorbs total fish production, specially trout production, having no distribution problems.

As far as marine waters are concerned , fish produced by the extensive method has no distribution problems since it is a high-value product with low yields. As regards semi-intensive and intensive aquaculture., problems may arise mainly in the case of juvenile production units, where costs of production are high.

MULTIANNUAL GUIDANCE PROGRAMME FOR AQUACULTURE

(1987–1991)

MAIN OBJECTIVES:

- DEVELOPMENT OF SUPPORT STRUCTURES;

- ENCOURAGEMENT OF RATIONAL USE OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND AVAILABLE SITES;

- IMPORTANT OF AQUACULTUE PRODUCTION.

GUIDELINES :

- TO PROVIDE FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF SUPPORT STRUCTURES;

- TO ENCOURAGE ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES APPLICATION;

- TO ENCOURAGE METHODS FOR HIGHER PRODUCTION LEVELS.

MULTIANNUAL GUIDANCE PROGRAMME FOR AQUACULTURE

(1992–1996)

MAIN OBJECTIVES:

- EXPANSION THROUGH BETTER UTILIZATION OF AVAILABLE SITES ON LAND AND OPEN SEA;

- HIGHER LEVELS OF PRODUCTION;

- SUPPLY THE CONSUMER WITH GOOD QUALITY PRODUCTS;

- ECONOMIC CONSOLIDATION OF FISHERIES TO PROMOTE REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT.

GUIDELINES:

- TO ENCOURAGE THE USE OF MORE ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES;

- TO REINFORCE TECHNICAL, AND ECONOMIC CONDITION IN ORDER TO ACHIEVE HIGHER LEVEL EFFICIENCY;

- TO ENCOURAGE INTEGRATED PROJECTS;

- TO STIMULATE FISHFARMERS FORMATION;

- TO PROMOTE: AND ENCOURAGE COLLECTIVE INVESTMENTS (SUCH AS ROAD NETWORKS, POWER SUPPLY, SEWAGE STRUCTURES, WATER CIRCULATION IN ESTUARIES AND OPEN LAGOONS, HATCHERIES AND REARING PILOT-UNITS.

LEGAL AND REGULATORY ASPECTS

DECREE LAW 261/89, 17 AUGUST

DECREE 980-A, B, C/89, 14 NOVEMBER

DEFINITE AQUACULTURE LEGAL REGIME AND PROCEEDINGS FOR ESTABLISHMENT AND LICENSING PROCESS.

ESTABLISHMENT PROCESS:

- PROPERTY RIGHTS (IN CASE OF PUBLIC PROPERTY A SPECIAL AUTHORIZATION MUST BE OBTAINED);

- LOCAL SALUBRITY CONDITIONS;

- NON-LOCATION NEAR MOLLUSCS NATURAL BANKS;

- NON-INTERFERENCE WITH NAVIGATION AND TIDAL MOVEMENTS:

- LOCAL CONDITIONS FOR PROPOSED STRUCTURES;

- ENVIRONMENT REGULATIONS:

- NON-COLLISION WITH OTHER ACTIVITIES.

ALL APPLICATIONS ARE ANALISED TWICE A YEAR

LICENSING PROCESS:

DEFINE OPERATION CONDITIONS, SUCH AS: SPECIES AND CULTURE METHODS, SUPPLY OF JUVENILES, FEEDING (SOME LIMITATION FROM ENVIRONMENT AREA), SANITARY DIRECTIVES.

LICENSES ARE GIVEN FOR THE YEARS, WITH THE SAME RENEWING PERIOD.

RESEARCH PROGRAMMES

- IMPROVEMENT OF LARVAE AND JUVENILES SURVIVAL STRATEGIES.

- FEED RATIONS, PARTICULARLY FOR LARVAE AND JUVENILES.

- DISEASES STUDY FOR ITS PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF DEVELOPED.

- NEW CULTURE METHODS INCLUDING OFF-SHORE AQUACULTURE.

- ZOOTECHNICAL IMPROVEMENTOF REPRODUCERS.

AGENCIES :

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE INVESTIGACAO DAS PESCAS(INIP)

FACULDADE DE CIENCIAS, LISBOA, (FCL)

INSTITUTO DE ZOOLOGIA/FACULDADE DE CIENCIAS, PORTO, (IZ/FCP)

UNIVERSIDADE DE ALGARVE (UA)

INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS AS BIOMEDICAS ABEL SALAZAR (ICBAS)

BY Mr. C. HOUGH

The domain of commercial aquaculture currently includes a wide range of different species, differing culture techniques and systems and is composed of farms whose scale varies from the family scale operation up to the large commercial farms.

However great the difference between one farm and another, the common elements to all commercial aquaculture projects are:

If one looks at the history of aquaculture and, particularly, the more recent promotion that the sector has been subject to, one could surmise that the importance of these two basic points has been underestimated.

One can cite the efforts that have placed into production of a species that is either unsuited to the target market or that requires to be processed before sale or needs to be moved to the market where the product is acceptable

Another simple criterion that must be referred to is that the total production costs must be lower than the selling price in order to make a profit and, hence, satisfy the investor that his money has been well placed.

If one a assumes that all the investors in aquaculture have done so in order to establish a profit-making enterprise one has to ask the question as to why do so many commercial aquaculture projects encounter severe financial difficulties in the course of their development?

From my own personal experience in the sector, one can highlight intrinsic elements in the economic structure of a typical project that can have a dehabilitating effect on its financial health.

1- CAPITAL INVESTMENT

The investment planning of a new project is often one of the most interesting part of its development for the promoters. It is rare, though, when the final investment figure is actually lower or the same as the original figure projected. The factors that encourage this phenomenon are varied - price increases, underestimated budgets, a desire for the «best» equipment and technology, poor control over contractors etc.

Such additional expenditure rarely damages-the economic projections including reference figures such as the International Rate of Return. For example, an increase in capital expenditure of 10% hardly affects this criterion. However, such as increase in expenditure does absorb cash, which was probably previously allocated for the project's operating coasts.

Depending on the financial structuring of the project's cash requirements (a subject that requires more than 30 minutes discussion) the promoters are generally wary of returning to banks and other shareholders for additional finance prior to starting production and the effects of this immediate problem are often not felt until later.

2- PRODUCTION DELAYS

Most people who have been involved in commercial aquaculture recognise that the first year's activities are generally subject to delays of one form or the other. Although this is a very generalised statement who has not encountered problems with equipment delivery, timely completion of engineering works, problems with local contractors not coming to finish half-completed works etc.? Obviously, these occurrences can and do after affect production.

It is essential also to allow for the «learning curve» of new staff have to adapt to the operating characteristics of a new site and, maybe, a workforce that has to be trained in a new activity.

Such situations can lead to a project having a full complement of staff working on a site that is complete but where production is lagging seriously behind the original forecast. For projects that are subject to seasonal growth conditions, 3 months delay can mean the loss of nearly a year's production.

3- STOCK ESTABLISHMENT & VALUE

Another important factor that need to be recognised is that of stock establishment; apart from farms that can buy fingerlings and finish all fish within the year, the general requirement is that a farm needs a stock of fish, ranging from fry through to saleable fish, that is the base of its production operations. The production forecast must always include such stock requirements and a monetary evaluation of the value of this item.

It is sometimes extremely difficult for technicians to come to grips with this particular problem and

there are many sides to the argument-how much is the stock really worth?

The stock has an inherent value to the farm since it is the basis of future revenue.

To the accountant, desirous of limiting losses on the year-end statements, such as value should be as high as possible - a means of soaking expenditure into a tangible asset.

To the investor, as low a value as possible (in a profit-making farm) increase profits.

To the market, unfinished fish smaller than the size required by the consumer) has little value.

In many cases, this situation can only be resolved by discussion with the Company's auditors and local tax authorities. My own experience is that one should attempt to have admitted a high value of stock (approximately 20–25% underneath the sales price/kg at the beginning of a projects history) which can then be reduced over time as efficiency increases.

4- WORKING CAPITAL

Stock establishment and working capital are integrated yet separate items in the economics of a fish farm and it is perhaps worth definite each again.

Working capital is the cash required by the project to cover principally the short term assets/debtors and liabilities/creditors. Identification of these items is extremely important in the planning of a project This item should not be confused with operating expenditure but forms an integral part of the true cash requirement of the project.

Liabilities & Creditors include personnel & staff, public and private services and any other item that is bought on limited credit (say, 15–90 days credit)-an obvious, important creditor for such projects is the feed supplier.

Assets and Debtors include sales where the monies have yet to be received, sundry stocks and spare parts and fish stocks.

The working capital Requirements is(the balance between the two sections and is a supplement to the real operating costs,

This seems simple enough but there are several realities that have to be faced:

if calculated on a year to year basic, one does not necessarily identify the peaks and troughs of

the cash situation particularly where, say, 20 months are required to grow the product to a marketable

size or debt repayments are made quarterly etc.

However, one must not confuse the working Capital Requirement with the Real Cash

Requirement which is the sum required to get the project through its teething stages up to the

]paint where Sales exceed Expenditure.

If this is can be illustrated in the following theoretical example.

1. A project is foreseen for the production of fish and all construction is complete and terminated prior to production starting in year 1., & the total investment id $ 3 million.

2. Production starts in Year 1, producing fry, fingerlings and juvenile fish - Operating Costs for the year were $ 600, 000 - some 30 tons are in stock at Year end and is valued at 10$/kg, giving a value of $ 300,000.

3. The project has a feed and spare parts in stock at a value of $ 20.000 and owes the staff and other creditors $50.000.

Following this example the working capital requirement is $ 270.000.

One must note that part of the operating expenditure has been converted into a short term asset and that the real cash expenditure for the year was

$ 600.000 billed operating costs less

$ 50.000 which the project owes - $ 550.000

1. In Year 2, 130 tons of fish are produced of which 120 tones are sold, leaving the farm with a year-end stock of 40 tons - valued at $ 400.000. The operating costs were $ 1.000.000 and the working capital requirement has changed considerably.

2. The project has sold 120 tones at $ 13/kg, representing a return of $ 1.560.000 but is owed money for, say 20 tones of fish sold - $ 260,000, leaving a cash-in-band return of $ 1,300.000.

Fish Stocks are valued at $ 400.000

Other Current Assets are Worth $ 70.000

TOTAL-$ 730.000

The project creditors have increased lightly to 4 80.000 therefore the Working Capital Required has increased from $ 270.000 to $ 650.000 (+$ 380.000).

The cash Requirement has to be calculated from the point at which real sales revenue (money in the bank) exceeds monthly expenditure. This is not the year-end balance projection and has to be calculated with precision.

If the project sold its fish thoughout the last 6 months of the year and its monthly operating costs are the same, it will have spent an approximate $ 5000.000 prior to sales. Thus the absolute cash requirement for this example would be:

$ 3,000,000 for investment

$ 550.000 for year 1

$ 500.000 for year 2

TOTAL - $ 4.050.000

It is evident that however one juggles with stock Values or Capitalization of Expenditure, the cash requirement does not change.

When these figures are translated into Profit & Loss Account, the manner in which they are presentation can often determine the financial incentives of the project.

The profit before Depreciation is simple to calculate being the Turnover less the Direct Costs of

Production and Operating Costs plus the difference in the Stock value (if stocks increases).

The pre-Tax profit Figure is obtained after deduction of Financial Charges and Depreciation.

Having been confronted by numerous potential investors, the statement that no divided will be

available for 3–5 years is generally accepted with disbelief. It is a life in aquaculture that it

takes a few years of profit-making in order to eliminate the accumulated debt of the initial years of

operation.

Comments on FINANCIAL STRUCTURING

It is often the case that the move into a profit situation coincides with the repayment of loan capital, if one has negotiated a suitable grace period, and these factors should at the worst coincide. Otherwise, the project may well find itself in a situation where it is theoretically bankrupt.

This situation has been encouraged by the overwillingness of investors to calculate the equity requirement of the project on a high loan/equity ratio, say 30% 70%, and even 20%/80%. The previously-mentioned understimated cash requirement and any incident that worsens stocks, operating expenditure or sales can then have a catatrophic effect on the financial security of the project.

From my own experience, it is often extremely damaging to a project to attempt to pay dividends within the first 4–5 year since this takes valuable cash of the project which is required for the establishment of its steady state.

The financial structuring of the project should cover adequately the total cash requirement, have an equity level equal to a minimum of 40% of this figure, use short term and medium term loans to assist stock establishment/operating costs and ling term loans for investment.

5- COSTS OF SALES

The financial sensitivity of a project to changes in Operating Expenditure is far more pronounced than to Capital Investment, it is even more sensitive to changes in the selling price.

Typically, an increase in operating expenditure of 10% may after then IRR by 2–3%. However for the same project, a decrease in the selling price of 10% would after the IRR by 4–6% (since the profitability is hit directly).

So, what are the cases where the true sales price would reduce?

Over the last few years, the aquaculture world has been hit by reductions in the value of some of its most successful products-notably salmon, prawns and trout - the reasons for these reductions are varied - supply exceeding demand being the most obvious.

However, one must mention that there are significant changes afoot within the market place-all of which affect the costs of sector-an item which is all too often underestimated or ignored in the financial projections of projects.

Costs of Sales should always be itemised separately and, where possible, be identified on a value.kg, including;

There is also the fact that damaged or sick have to be withdrawn and that such products cannot be sold at the same value. It is extremely rare that 100% of the farm's «sales» will actually be paid for.

Within the EEC, significant changes have occurred within the markets that have combined to increase the value of the Costs of Sales.

Prices quoted are generally C&F or CIF - meaning that the project has to bear these costs within its own expenditure.

Quality requirements are higher - particularly when dealing with the supermarkets and other large distribution chains - meaning that there are more rejections and where fresh fish are concerned-more disposals.

The consumer requirements are moving irrevocably towards standard products (e.g.a 250 g trout) which means that fish outside of a pre-defined range may well have a lower value.

The requirement for fillets or de-boned fish is increasing-imposing a level of processing and the associated investment and operating costs for doing this.

The companies active in the wholesale sector are issuing Product Specifications to which a supplier must adhere - any variation from the guidelines means almost certain rejection and potential loss of a buyer.

Such specifications covers size and the graded range of the product, freshness, acceptable bacterial levels, packaging and labelling.

6- MARKETING

One should not forget any marketing efforts as may be required - including visits to potential clients, documentation and the communication costs associated with sales.

There is little doubt that no sector in aquaculture can sit back and think that the inherent quality of its product will guarantee sales at the best price. Understanding market forces and being prepared to invest in marketing is essential at this time.

The general trend within the EEC is that fish sales are moving into the supermarkets where a special counter is made over to fish products. Some of the top-range supermarkets are insisting that even fresh fish are packed in Controlled Atmosphere packs in order to gain some extra days of shelf life.

This situation affects both the market and the producers. Presence in the supermarkets generally infers a higher market volume but at a lower price and with higher quality specifications. It is often difficult for a single producer to make an impact on a supermarket chain and grouping of suppliers is generally necessary, requiring producers to work together. Such cooperative effort will almost certainly be required by the smaller aquaculture projects in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

The technical success of aquaculture has brought the sector much attention and has attracted a great deal of private and public investment. The principle virtue of the species reared has generally been that of a high level of appreciation by the consumer, accompanied by a high (initially) sales value. Figures for decreasing fishery catches have served to encourage the general optimism for investment in aquaculture.

A growing number of projects providing fish to the markets have encountered difficulties in maintaining the desired sales values, and volumes primarily due to understandable market forces.

It seems unlikely that the markets will alter much in the near future and that the whole of the aquaculture world will have to adapt to the fact that it must manage its affairs in an efficient and business-like fashion.

On the production side, cost-effective management and efficient production are essential: it is to be noted that the FCR for trout has been reduced from 1.8–2 to below I within the last 10 years. I man empoyed now produces>100 tons of fish on an efficient farm.

On the marketing front, producers will need to be better organised and well informed. Understanding market forces and characteristics must be an integral part of the job of the professional aquaculturist.

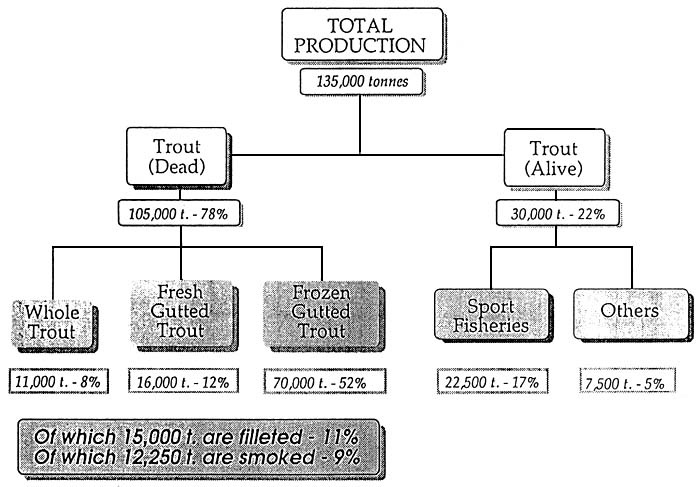

Distribution of trout farms by number and by size.

Production estimated at 143,595 tons (1989).

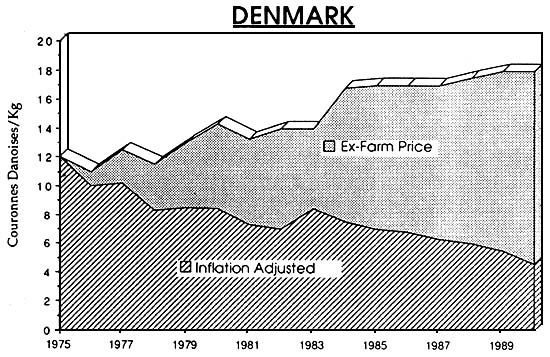

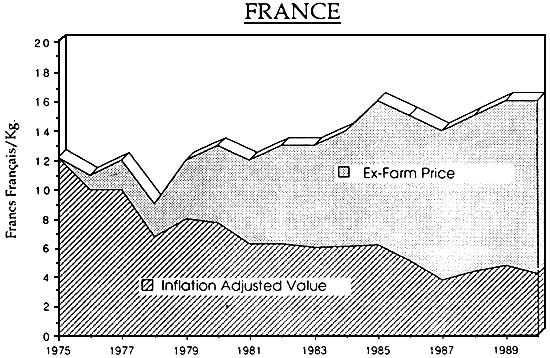

Comparison of the “Ex-Farm” Values of Portion-Size trout and adjusted in line with inflation

Soures: FES and SUSAN SHAW 1986

TRENDS OBSERVED FOR RETAIL PRICES FOR SALMON &TROUT 1970–1987 (FRANCE)

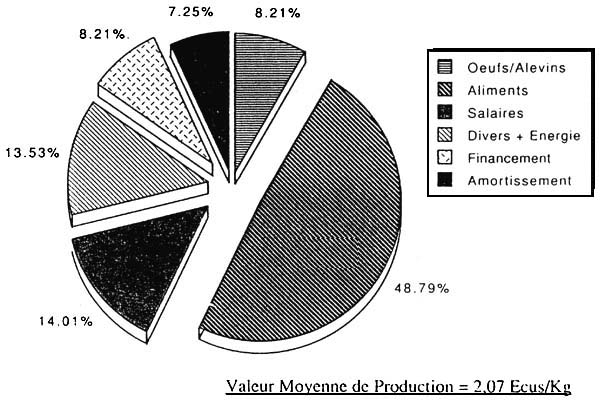

| LIBELLE | Ecus/kg | % |

| Coût de l'Alevin | 0,17 | 8,21 |

| Aliments | 1,01 | 48,79 |

| Main d'Oœuvre | 0,29 | 14,01 |

| Divers dont Energie | 0,28 | 13,53 |

| Amortissements | 0,15 | 7,25 |

| Frais Financiers | 0,17 | 8,21 |

| Coût de production | 2,07 | 100 |

Ventilation des Coûts de Production

Value Moyenne de Production = 2,07 Ecus/kg

Working Capital

| YEAR 1 | YEAR 2 | |

| Current assets | ||

| fish stocks | 300.000 | 400.000 |

| other stocks | 20.000 | 70.000 |

| Debtors | - | 260.000 |

| 320.000 | 730.000 | |

| (410.000) | ||

| Current debt | ||

| CREDITORS | 50.000 | 80.000 |

| BALANCE | 270.000 | 650.000 |

| (380.000) |

PROFIT/LOSS.

| YEAR 1 | YEAR 2 | |

| Operating coasts | 600.000 | 1.000.000 |

| Stock value | 300.000 | 400.000 |

| (100.000) | ||

| Result before receipts | 300.000 | 900.000 |

| Sale Receipts | 0 | 1.560.000 |

| Result before depreciation | 300.000 | 660.000 |

| Depreciation | 400.000 | 400.000 |

| Loan Repayment | 200.000 | 300.000 |

| Result before tax | 900.000 | 40.000 |

BY Dr James F MUIR

Scotland

1- INTRODUCTION

Sustainability; the various definitions; the aim of sustainability in aquaculture; the need to identify means in which sustainability can be assessed

To be effective and ‘sustainable’, production systems must however operate within the biological and ecological constrains of the stock produced and the environments which they inhabit, and it is in the direct interest of the producer to be environmentally protective.

One of the most widely used concepts in current thinking on development, social and economic management production systems, sustainability is now stated to be the local, national or global goal of governments, international agencies, conservation groups….

At simplest level taken to mean activity can be kept going in at least the medium term future, and is not dependent on a rapidly depleting input or set of inputs - in the development field often external financial support and/or technical skill.

In the more general sense, implying no diminution of future potential, the provision of ‘intergenerational equity’, ie that each generation has equal access to the ‘goods’ of the world; also sense of at least maintaining, possibly increasing ‘capital stock’-defined strictly as physical resources, quantity and quality, but also extendable to include eg human skills, technological potential, sources of satisfaction, etc which would allow for depletion of one or more if matched by gain in other areas.

Generally anthropocentric, eg does not provide for ‘interspecies equity’ as some conservationists might argue; also essentially utilitarian, and basic difficulties with the ‘mixed capital stock’ approach…

2- Problems of definition and application

Although the concept of sustainability is reasonably easy to grasp and even to talk about, there are surprising problems in pinning the concept down to workable definitions which will allow use to make rational choices in resource use, project selection and development, etc.

At the first level, consider the different uses of the concept :

- in terms of project, usually refering to immediate, localised sustainability - eg with development projects, the question of whether activities will continue: once external support has been removed; the role of human resources, external inputs of technical advice, servicable vehicles, fuel, feeds etc;

- in terms of social acceptance, continued support, interest, involvement

- in terms of ecological stability, eg with projects which modify their environments or cause localised depletions: again a short to medium-term consideration;

- in terms of financial robustness, with respect to varying operating conditions, market prices, input costs, etc;

- in terms of resource use, at a local, regional or global level: ie is the activity depleting in nature, does it maintain an approximate balance of resource inputs and outputs, or does it indeed create a net gain?

A second area of difficulty follows from this range of concepts, which though often related, need not be mutually inclusive; ie a project or activity may be socially acceptable but ecologically unsustainable; a development project may target a range of activities which are financially, socially and ecologically sustainable, but due to its method of organisation and operating may not be institutionally sustainable. Similarly a project which is locally depleting may be globally gaining, or vice-verse. Many projects or activities involve the use of different mixtures of depleting and non-depleting resources; how can the relative merits of these mixes be evaluated? In such circumstances, how are measure all these different facets, and can we balance one against another to make rational choices?

Then there are the underlying methodological questions; even more contentions and problematic, such as;

- the fundamental economic problems of assigning ‘real’ values to inputs and outputs; measuring the value to society of one output versus another; the changing value with changing demands and changing supply;

- the difficulties of determining future values of primary resources given technological change and the changing ‘factor mix’ potential of these resources; also likely changes in societal choice and preference;

- the difficulties of predicting every outcome, particularly eg of cumulative small-scale local changes on larger scale global changes;

- is sustainability a good thing? Should it be a uniformly dominating issue; it cannot be defined satisfactorily, might this lead to more dangerous errors and inefficiency ?

One of the commonest starting points for judging sustainability is that of the non-depleting characteristics of the activity; as the above points might suggest, outside of rather crude comparisons, this approach may be neither simple or accurate. In the aquatic resource field we are dealing with a wide range of interlinking issues, in a environment which is not by its basic nature easily measurable. The aim of the following sections is to be consider the use and limitations of conventional appraisal techniques, or modifications of them, in addressing the issues of sustainability in aquaculture.

3- Environmental economics

One of the classical difficulties of environment economics has ben the management of common proper resources and the difficulty of assigning value to ‘intangibles’, Bojo (1991) comments on environmental damage, identifies:

- information failure

- market failure

- policy failure

- as contributing to wrong decisions - but how to make right decisions?

While concepts of environmental economics may be easy to describe and intuitively sensible to accept, they provide a host of methodological problems, not least of which is that of defining environmental effects in the forms measurable by conventional economic analysis and by which economic decisions are normally made. There are important qualifications, depending on whether the effects we are concerned about are :

- absolute eg with effects which are considered to be unacceptable societally, where absolute values are transgressed-cutting off water to poor villagers, introducing heavy metals or radionucleides into the water or food supplies;

- relative, eg with effects which may be partially acceptable by society, in the understanding that they may be sacrificed for a perceived greater good, and that the issues can therefore enter the ‘assessment arena’

There are further points to consider :

- absolute issues and values are societally determined, ie they do not have intrinsic characteristics; at the margins they may be determined differently by different groups within society;

- relative values, and particularly the weighting given to specific factors or characteristics are also societally determined, and may change;

- value concepts may be altered by changing perception, by information (or disinformation); even absolute value may be effected;

These ideas are echoed in the expression of instrumental and utilisation arguments (Randall, 1991)-eg for biodiversity, also argument for ecosystem support and human cultures. Use values, aesthetic and recreation values, existence value wrt satisfaction of knowing of existence of state of affairs. River-popper argument, but is there catastrophe theory? Do we know the breakpoint? Does Gaia concept have anything useful to say?

Alternative arguments-correspond to the absolute values described above; right action defined by moral imperatives; duty-based theories define obligations of humans to other living things, resolve conflicts by reasoning-change acceptable when all affected parties, with enforceable rights, agree, otherwise status quo 'contraction thought experiments?

Dangerous of utilisation approach defined as : human utility function, instrumentalist arguments; divide and conquer strategies, tradeoffs ‘assigning value to that which we do not own whose purpose we cannot understand except in the most superficial ways is the ultimate in presumptuous folly’ - at the practical level, can we decide on something whose value we may not appreciate until future?

Also the weber concepts of traditional, religious/charismatic, legal/rational basis of action - bow does this place our choices/ Problem of scientific assessment placing absolutes into the realms of utility? is this a bad thing? Can traditional systems of societal control and preference be recovered? Can we strive for a moral imperative?

Finally there is the problem that we must find some framework for decision-making which at least incoporates these aspects, and ensures that wider considerations can be brought in, that choices are not made without regard for these factors; problem of stand-off-can ‘absolute’ or ‘moral’ values be upheld and regarded if proponents refuse to allow them into discussion and the ‘slick terrain’ of the economists? Will political process provide the protection-note the aim by many conservationists to aim for exactly that, by passing the debating grounds, going for the ‘hearts and minds’… might there be a ‘conservation fatigue’?

Alternatively, Randall's argument, can we incorporate ‘binding behaviour’ and define ‘SMS’ safe minimum standard approaches to decisions? Finally, do we have a system of ‘international environmental’ economics-can we control international trade in pollution-poor countries will accept the pollution for a price-either directly, eg nuclear wastes, or indirectly by producing with cheap and dirty methods….

4- Assessment techniques

Returning to the ‘real’ world of aquatic resource management, it would first be useful to consider the typical planning and project cycle; this process is typical both of commercial and public-sector activities; the application of measures and concepts of sustainability can be carried out at any stage of this cycle, eg;

- identification and clarification of initial concepts;

- preliminary resource and location assessments,

- planning and pre-development, organisational structures

- laboratory, field and other research/removal or reduction or project uncertainties

- commercial development, definition of priorities,

- monitoring, post-evaluation;

- evolution, expansion

Assessment techniques are most widely considered in the initial stages-eg feasibility studies, and in the operating/post-operational stages-eg evaluation studies; however, the range of management accounting and audit techniques can be usefully employed throughout the lifecycle of the project.

For general feasibility assessments, and for monitoring and evaluation, a range of techniques is conventionally employed; these include:

- standard technology descriptions; variations; the evolution of ‘technology packages’; identification of the various forms of risks

- conventional financial appraisal techniques; payback, NPV, IRR, gross returns, returns on equity, simple farm budget returns;

- economic appraisal techniques; with wider benefits and disbenefits identified

A wider of techniques is currently under development; these include :

- incorporating the social dimensions; parallel social evaluations; assessment of value, choice, motivation, preference

- techniques incorporating environmental economic concepts; simple ‘environmental audits’; defining values energy accounting, ghost land assessments

- Farming systems approaches; FSR and FSD and variants

- Lifecycle costing: this is implicit in energy costing, but may also be applied to other forms of analysis, the main point being that a process or product should be defined across its entire lifecycles;

- for processes, including production capacity, input resources and their full costs, operating inputs, disassembly/conversion and disposal of waste materials, redundant equipment, etc.

- for products, including, entire inputs to production, use, disposal, decontamination, etc.

There is also the question of the extent to which simple techniques may be ‘fine-tuned’ to address sustainability issues:

- the use of matrices and decision-tress; to relate and compare the various ‘sustainability’ measures; note he need for defining absolute vs relative concepts;

- the wider and more searching use of sensitivity analyses; incorporating changing real values; also the possible use of dummy variables such as energy (carbon) taxes, depletion taxes, etc;

- the use of shorter and longer time-scales for financial evaluation

- the need to sec smaller scale projects within the larger-scale context; eg multiplied and/or ‘nested’ at the regional or higher level

5- Predictive strength;