A total of 31 PPD were interviewed from 23 villages across ten counties, four townships and three cityships in two provinces. The interviewees’ ages ranged from 24 to 67 years, with an average of 40 years; one woman and 30 men were interviewed. All the interviewees were married and had from zero to ten children. Of the interviewees, 27 were literate and four illiterate. The formal education received by literate interviewees ranged from one to 12 years, with an average of seven years.

Interviewees’ physical disabilities included locomotor problems caused by amputation and lameness (16 persons); general handicaps (four persons); paralysis (four persons); and others (four persons). The percentage of disability ranged from 25 to 75, with an average of approximately 40 percent. Interviewees had been disabled for ten to 52 years.

PPD, agriculture and extension

At the outset of the study it was assumed that rural PPD had no, or only very limited, sources of income and employment. However, field surveys revealed that 20 of the interviewees received a regular monthly salary or allowance from government agencies or public foundations; nine earned an income from agricultural business; and the remaining two were employees of government agencies (Table 1). Ten interviewees had been financially supported by the agricultural bank, three by other banks, while the rest had not received any such support.

A woman who is blind in one eye, collecting wood for her family

Table 1

Interviewees income and occupational conditions

|

Conditions |

Findings |

Total responses |

||

|

Source of income |

Farming business |

Monthly allowance |

|

|

|

9 |

20 |

31 |

||

|

Monthly salary |

|

|

||

|

2 |

|

|

||

|

Ways and means of securing income deficit |

Farm activities |

Welfare agencies |

|

|

|

22 |

3 |

31 |

||

|

No reply |

|

|

||

|

6 |

|

|

||

|

Type of employment |

Private business |

Government agency |

|

|

|

11 |

2 |

31 |

||

|

No reply |

|

|

||

|

18 |

|

|

||

|

Farm landholding |

Landowner |

Renter |

Sharer |

|

|

26 |

4 |

1 |

31 |

|

|

Seasonality of occupation |

Seasonal |

Permanent |

Temporary |

|

|

25 |

5 |

1 |

31 |

|

|

Need experience and skills for occupation? |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

27 |

4 |

|

31 |

|

|

Trained for occupation? |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

8 |

23 |

|

31 |

|

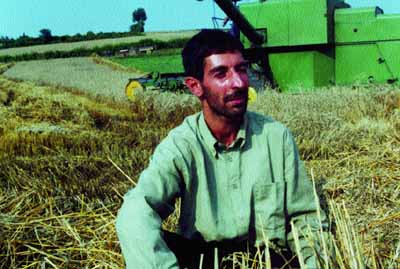

Most of the PPD had seasonal farming employment, a few had permanent employment, and one had temporary employment. About 26 of them were involved in cereal production - mainly rice and some wheat. Nine were involved in oilseed production and the cultivation of fruit trees. In addition to these activities, some of the farmers with disabilities also engaged in animal husbandry, silkworm keeping and poultry production as side-activities; most interviewees were engaged in more than one activity.

Generally, interviewees had gained their farming skills and experience traditionally, from parents and relatives; a few of them had received extension training. Only about ten interviewees had been helped and encouraged to engage in farming; the rest had entered it as a result of their own personal interest. They had been guided in their farming activities by extensionists, local leaders, other farmers and their relatives; but five had not received any farming guidance at all.

All but four of the interviewees felt a need for additional skills and experience in farming operations; three-quarters of them had never attended any extension training classes, courses and/or meetings. In many cases, however, the production yields and farming efficiency achieved by farmers with disabilities were similar to those of able-bodied farmers who had attended extension training activities.

All rural people, especially farmers, are clients of the School of Agricultural Extension Education. This means that rural PPD, especially if they are engaged in agricultural activities, should be considered clients of the school. However, how aware are farmers with disabilities of this facility? And do extensionists recognize and accept the unusual situation of farmers with physical disabilities? In regard to these questions, it should be mentioned that, if PPD are aware of their legal rights with respect to training and extension education services, they must try to acquire access to such services. Similarly, if extensionists recognize and accept PPD as a special client group, they should try to serve that group in accordance with its special situation.

A farmer with disability and his wife prepare for chemical spray of their field following a method which is considered unsafe and dangerous

The results of the survey showed that farmers with disabilities were not aware of their rights and that extensionists did not recognize and accept the unusual situation of farmers with disabilities as a special client group. Although most interviewees knew the Agricultural Servicing Centre and the local agricultural extension agents, 18 of them never had contact with or met agricultural extension agents. In addition, the vast majority had received no previous training contacts or extension meetings from Jihad Rural Trainers.

Among the group who did have contacts and meetings with Ministry of Agriculture extensionists, 19 persons had met the extensionists in their homes or farms, and the rest in extension offices or training centres. It was revealed that the extension training methods at these meetings included lectures, demonstrations, farm visits, film shows and radio and television aids.

Table 2

Expectations of farmers with physical disabilities

regarding extension and training activities

|

Conditions |

Findings |

Total responses* |

||

|

Suitable place for training visits |

Farmers home |

Workplace |

Extension office |

|

|

9 |

9 |

10 |

27 |

|

|

Training centre |

Public places |

Rural farms |

|

|

|

None |

5 |

7 |

|

|

|

Preferred training methods |

Radio and TV |

Film |

Publications |

|

|

13 |

4 |

14 |

|

|

|

Lectures |

Extension meetings |

Demonstrations |

30 |

|

|

5 |

3 |

20 |

|

|

|

Face-to-face |

Practical |

Farm visits |

|

|

|

training |

training |

5 |

|

|

|

19 |

7 |

|

|

|

|

Post-training expectations from agencies |

Production |

Supportive loans |

Primary materials |

|

|

credit |

24 |

18 |

|

|

|

22 |

|

|

|

|

|

Storage services |

Marketing services |

Farmland |

|

|

|

2 |

14 |

9 |

30 |

|

|

Rangeland |

Improved cattle |

Improved inputs |

|

|

|

None |

2 |

9 |

|

|

|

Special tools |

Tools and facilities |

Social motivation |

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

7 |

|

|

* Interviewees mentioned more than one item in their replies.

It should be mentioned that all contacts and meetings with extensionists were directed to rural farmers in general, with farmers with disabilities taking part if and when they could. In other words, no activities had been planned specifically for farmers with physical disabilities.

Regarding the post-training assistance and support they expected from the agencies to help them put what they had learned into action, all but one of the farmers with disabilities mentioned at least one of the following: loans to support production, farm credits, primary materials for handicrafts, marketing services, farmland, improved inputs, social motivation and other necessities.

Problems and solutions

The most common problems and difficulties that interviewees faced in agriculture were lack of knowledge in selecting appropriate varieties of seed crops, lack of experience in pest and disease control and lack of production inputs and irrigation water. A few mentioned other factors including soil salinity and flooding.

Regarding suitable training to solve these problems, 17 of the interviewees suggested courses in plant pest and disease control, nine asked for courses in the proper use of inputs, and five requested courses in how to select appropriate improved seeds and in methods of irrigation and land preparation.

Most of the interviewees proposed the provision of tools and inputs and the granting of low-interest loans as being the best economic facilities to help solve their farming problems and difficulties. Almost all of them reported facing no social problems in the course of their agricultural activities. Most of them, especially the war veterans, felt themselves to be well respected in their societies.

A woman farmer carrying food on her head for her family members working on the farm

The physical difficulties faced in farming included the impossibility of preparing land, the problem of transporting heavy inputs and products, and their inability to perform other heavy farming jobs. Interviewees suggested the provision of suitable tools and machinery and special training in carrying out farming tasks in easier ways as options for resolving or decreasing these difficulties.

The farming-related needs, wants and recommendations of farmers with disabilities were very similar to those of their able-bodied colleagues. In fact, the similarity in responses was so great that it is difficult to distinguish between the expectations of able-bodied and those of farmers with disabilities, although the latter group has to contend with the additional effects of their physical disabilities.

Of the 31 farmers with physical disabilities interviewed, only 24 had relatives who were available for interview with field surveyors. These relatives were interviewed at 20 villages in six counties, four townships and two cityships of the province of Mazandaran.

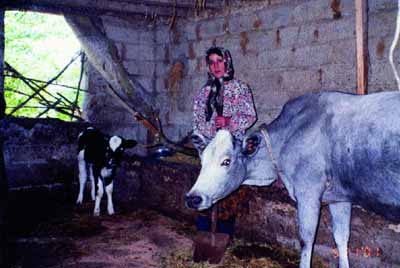

A farmer who is semi-paralysed, as home producer of cattle

The ages of 20 of these interviewees ranged from 15 to 66 years (four relatives did not mention their ages). Of the 24 interviewees, 18 were men and six were women; eight were illiterate, seven had received elementary education, six intermediate education, two secondary education, and one college education. Four of the interviewees were the sons, six were the wives, six the brothers and eight the fathers of the disabled person.

Farmers with disabilities and assistance

According to the interviewees, all of the farmers with physical disabilities were very willing or willing to receive general assistance from their relatives; and most were interested in technical guidance in agricultural activities from their relatives. However, only one of the relatives had received special training in helping PPD.

Interviewees declared that they had been helping and training their relatives with disabilities for many years, especially in such operations as rice cultivation, the use of manure and green fertilizers and plant pest control. Relatives stated that farmers with disabilities were indeed ready to accept such assistance, because of much mutual confidence between the farmers and their relatives and the guidance and training offered by the latter had been found to be effective. When helping their relatives with disabilities, most of the interviewees had received encouragement, support and collaboration from other close relatives, local leaders and other farmers. Only two of them mentioned extensionists.

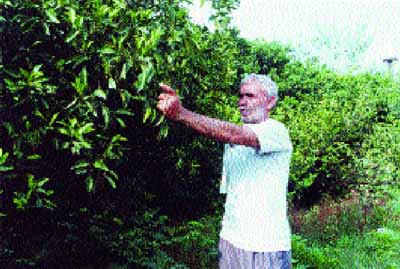

A farmer with only one hand surveying his citrus orchard to determine proper time for pest control

Farmers with disabilities also generally accept guidance in farm operations from other people (although not quite as readily as they do from relatives). Most relatives thought that this was because the farmers with disabilities usually respect experienced farmers and are very interested in gaining new knowledge and skills. However, about 20 percent of interviewees mentioned that their relatives with physical disabilities believed themselves to be experienced enough not to need the help of third parties.

According to most relatives, farmers with disabilities carried out farm monitoring and management, seed cleaning and disinfection, mechanical harvesting, weeding, seeding and grafting satisfactorily; while activities related to land preparation, input and product transportation, fertilization, pruning and hand-harvesting were not performed satisfactorily.

Seven interviewees helped their relatives with disabilities because of emotional relationships, eight claimed it improved the economic condition of the family, and the remaining 13 interviewees were motivated by family commitment and satisfaction. The sort of assistance that relatives were giving included physical help with agricultural operations, especially heavy jobs, providing farming tools and marketing farm products.

Recommendations and expectations

On the basis of their experience, the relatives recommended that special attention should be paid to the viewpoints of the PPD themselves; abilities, competencies and efficiencies of farmers with physical disabilities should be appreciated, and their disabilities disregarded, by those who come into contact with them; and full attention should be paid to the recommendations of farmers with disabilities, while taking account of their personal needs and remembering that they depend on family support and assistance.

Regarding the cooperation, assistance and services that they expected from other people, private institutions and public organizations to help PPD to continue their agricultural activities easily and more satisfactorily, interviewees recommended more technical and financial support, more facilities for providing farming inputs and loans, special training, more social respect and follow-up on requests.

A total of 23 agricultural extension managers, experts and agents were interviewed in the provinces of Mazandaran (20 persons) and Kohgiluyeh and Boyer Ahmad (three persons). The extensionists came from nine cityships, two townships, seven counties and five villages across the two provinces. Six of the extensionists were agent-technicians, 15 were B.Sc. experts and two were extension specialists with M.Sc. degrees.

The extensionists’ lengths of service at the Department of Agriculture ranged from three to 30 years, with an average of 14 years, as general agriculturists in the fields of crop, fruit tree and animal production, as well as other related fields. Their length of service as specific agricultural extension field workers ranged from three to 27 years, with an average of 12 years.

Since it seemed that this was the first time that the extensionists had been contacted to express their ideas about PPD engaged in agricultural activities, they were asked to identify the types of physical disability that were most common among rural people in the study area. In response, the extensionists mentioned paralysis, locomotor problems, lameness and amputations, as well as blindness, deafness and muteness, as being the most important disabilities. Almost three-quarters of the interviewees believed that digestive and other internal diseases were additional causes of physical disability among rural people in the province of Mazandaran.

Since physical disability is originally defined as a person’s partial or total loss of working capacity (ILO, 1965: 3), such diseases could be considered primary sources of physical disability among rural people. However, in this study digestive and internal diseases were not considered as physical disabilities.

Most of the extensionists estimated the frequency of physical disability among the rural people in their areas as being between 0.1 and 0.6 percent (i.e. between one and six persons out of every 1 000). This is far lower than the figure of 10 percent that medical specialists estimated as accounting for all types of disability.

Twin sisters with physical disabilities cultivating their farm

The extensionists listed the main agricultural activities of PPD in the study area as rice and wheat production, citrus tree growing, production of soybean, cotton, vegetables, oilseed and other cash crops, animal husbandry, sericulture and poultry production. These were the same as the activities reported by the farmers themselves.

Most extensionists stated that the production yields and efficiency of farmers with disabilities were satisfactory.

Table 3

Extensionists views of farmers with physical

disabilities

|

Subjects |

Findings |

Total responses |

||

|

The yield and efficiency of farmers with physical disabilities are satisfactory |

Yes |

No |

No reply |

|

|

15 |

7 |

1 |

23 |

|

|

Reasons for satisfaction |

Yields are equal to those of able-bodied farmers: 5 |

15 |

||

|

Farmers with disabilities do their best in farm production: 5 |

|

|||

|

Good management and follow-up, continued contact with relatives, use of others experience: 5 |

|

|||

|

Reasons for dissatisfaction |

Do not follow extensionists advice: 2 |

7 |

||

|

Cannot perform heavy jobs: 2 |

|

|||

|

Use paid labourers and others: 3 |

|

|||

None of the extensionists had ever received any organizational circular, directive or guideline to help them educate and train farmers with disabilities. Eight of them stated that they had no need of special directives because they met and served their clients with physical disabilities as though they were able-bodied.

Regarding interviewees’ proposals for ways in which the related institutions could improve the working ability of farmers with disabilities, more than two-thirds of them suggested the provision of medical aids and tools, and the remaining one-third suggested the provision of appropriate farming tools. According to most interviewees, the support that would best help farmers with physical disabilities to establish and/or extend their agricultural activities was the provision of production credits and loans for farming.

Most of the interviewees believed that the organizations and institutions concerned should establish special training programmes in accordance with the needs and possibilities of farmers with disabilities, so that they can continue their activities in agriculture. Most also believed that priority must be given to the formation of practical training courses to be held at the homes or farms of their clients with disabilities. They also emphasized the need to offer special training courses to the relatives and family members who work, help and/or live with the farmers with disabilities.

In addition to these proposals, the extensionists also suggested that extension volunteers who want to serve farmers with disabilities must be trained and employed, so that they can carry out this important new task properly. Other suggestions included simplified training courses, educational films and publications, and innovative and appropriate extension teaching methods.

Once again, regarding what concerned organizations and institutions should provide to help PPD to work in various fields of farming, most interviewees mentioned agricultural tools, inputs, credits, loans, land and improved cattle breeds under simple, specific terms. Some emphasized training, encouragement and service provision at the homes and farms of the farmers with disabilities.

An elderly farmer with only one hand uses a tractor to perform almost all farm activities

The extensionists implied that support should be based on some sort of subsidy. Since farmers with disabilities are scattered over rural areas, and therefore difficult for concerned agencies to reach, it was suggested that special groups should be established. Most of the extensionists stated that concerned institutions and organizations could assist PPD to form production or professional cooperatives, societies and/or special farmers’ groups at the national or regional level. Such an approach would help PPD to improve their farming activities and support each other within society, as well as strengthening their voice in private institutions and government agencies, all of which would protect economic benefits of farmers with disabilities and their right to live in peace and security.

Several interviewees did not approve of such special groups because they believed that farmers with disabilities should not be separated out from farmers in general. They stated that it was better to assist and encourage farmers with disabilities to acquire membership in general farmers’ cooperatives, societies and social and professional groups.

With respect to the education and training that extension field workers should receive before working with farmers with disabilities in rural areas, 18 interviewees stated that field workers should attend special courses in social psychology and sociology, as two of the basic fields of extension education. The rest emphasized training in communication and special teaching methods, so that field workers can easily transfer their messages, technical points and recommendations to their clients with disabilities.

A farmer who is blind in one eye, operates a mechanical harvestar

According to extensionists, the most effective extension teaching methods for training courses and extension meetings with farmers with disabilities would be film shows (but obviously not for the blind), demonstrations of methods and results, and farm visits. Afew stated that, for the literate, the preparation and distribution of simplified printed materials was more efficient.

For extensionists, the training of farmers with disabilities is an arduous task, especially when it has to be carried out in addition to their existing responsibilities. There is therefore a need for strong incentives. Good working facilities must also be provided to the volunteer extensionists who assume such a special task.

Most interviewees proposed appropriate bonuses, larger monthly salaries, field allowances, payment of overtime, and annual promotion and rewards as ways of motivating extension workers who want to work with farmers with disabilities. A few added psychological support and appreciation, vehicles and special training courses. Some interviewees suggested that such an important job should be performed by specialists who had been specifically trained and employed for the task.

Interviewees suggested many different ways of linking extension education for farmers with disabilities to the administrations and agencies concerned. These included adding a new branch to the existing structure of agricultural extension departments, establishing a bureau to monitor and follow-up on solutions to such farmers’ problems, and forming an information agency. Some also suggested the formation of independent support societies, training units, servicing units and/or consultation agencies.

This was the first time that the extensionists had to consider such an issue, so it is perhaps not surprising that there was no agreement among them. The responses also indicated that interviewees were not aware of any existing organizations and institutions that were fully or partially involved in the education and training of PPD in the fields of agriculture: and, in fact, no such agency exists.