System-wide capacity development and climate-smart agriculture

C1-1.1 What are capacity and capacity development?

“Development is like a tree – it can be nurtured in its growth only by feeding its roots, not by pulling on its branches.” (I. Serageldin)

Capacity is defined as "the ability of people, organizations and society as a whole to manage their affairs successfully.” Capacity development is defined as “the process whereby individuals, organizations and society as a whole unleash, strengthen, create, adapt and maintain capacity [...] to set and achieve their own development objectives over time” (OECD, 2006). Capacity development encapsulates both the overall aim of development (i.e. the “what”) as well as the process (i.e. the modality or the “how”) by which more sustainable results with higher impacts can be achieved (OECD, 2008).

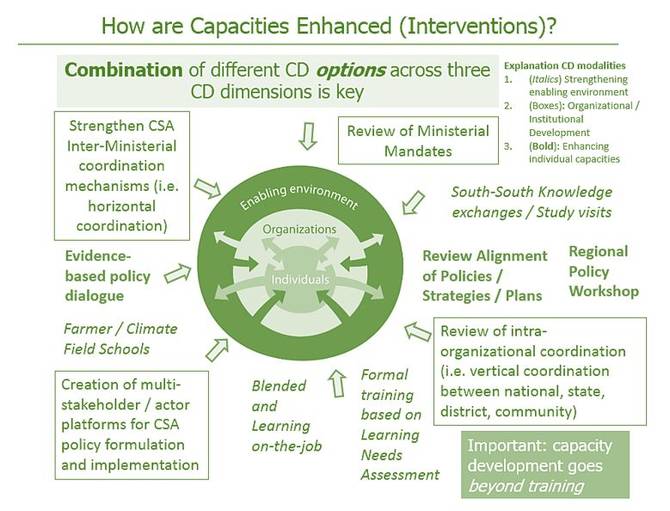

System-wide and effective capacity development aims to achieve more impactful, transformational andsustainable results at scale by facilitating a sustainable and endogenous development process rooted in national empowerment that enables countries to be in the driving seat of their own destiny. Contributing towards a new development paradigm (Stiglitz, 1998), system-wide capacity development aims to enable countries to own, lead and drive the development process aligned with national priorities, and with external actors (such as FAO) facilitating this transformation process. Operationally, system-wide capacity development goes beyond isolated training, technical assistance and policy support. Instead, interdependent, participatory approaches need to be applied to jointly assess capacity needs, design contextualized capacity development intervention and monitor capacity development results across the three dimensions of capacity development (see figure C1.1 and more detailed explanation below) to achieve more sustainable, country-owned and impactful results at scale.

Figure C1.1. The three system-wide dimensions of capacity development

- Source: Author adapted from FAO, 2015a

To achieve any system-wide change at scale in the way food is produced sustainably in the context of climate change, a CSA and food systems approach needs to be adopted and all three dimensions of capacity development need to be addressed holistically and interdependently.

C1 - 1.1.1 "Enabling Environment” dimension

The enabling environment dimension of capacity development is defined in this module as “the context in which individuals and organizations put their capabilities into action, where capacity development processes take place. It includes the institutional set-up of a country, its implicit and explicit rules, its power structures and the policy and legal environment in which individuals and organizations function” (FAO, 2015b). It addresses the systemic impediments regarding political commitment and vision, and policy, legal and economic frameworks; national public sector budget allocations and processes; governance, power structures, social norms, incentive-systems and institutional linkages.

C1 - 1.1.2 “Organizational/Institutional” dimension

The organizational and institutional dimension of capacity development includes public and private organizations, civil society and networks of organizations. It addresses: performance of organizations; cross-sectoral, multi-stakeholder horizontal and vertical coordination and collaboration mechanisms; strategic management functions, structures and relationships; information, knowledge-sharing and decision-making processes; human and financial resources; and infrastructure (FAO, 2015b). Organizational capacity development aims to strengthen performance within (i.e. intra) and between (i.e. inter) organizations. This module will focus on inter-organizational and institutional strengthening, such as examining horizontal and vertical coordination between and within organizations and institutions including at the local and landscape levels, thus complementing the original CSA Sourcebook chapter on local institutions. It will also examine multi-stakeholder and multi-actor platforms, processes and networks. Strengthening intra-organizational performance will not be examined in detail, as holistic organizational analysis and development is extensively covered elsewhere (Anyonge et al., 2013; FAO, 2013a; CSEND 2002; North 1990 and 1994).

C1 - 1.1.3 “Individual” dimension

The individual dimension of capacity development refers to the technical and functional knowledge, skills, competence levels and attitudes of individuals. These can be addressed through facilitation, effective learning activities and competency development (FAO, 2015b, 2012a, 2012b, 2013a). In the realm of CSA, it will be particularly important to develop targeted individual capacity strengthening efforts for different types of individuals, including producers, extension professionals, researchers in national research institutions, local government officials, district government officials, and national government officials across relevant ministries (e.g. environment, agriculture and finance).

Figure C1.2. Interventions across three dimensions of capacity development

- Source: Author adapted from FAO, 2015a.

C1-1.2 Methodologies and good-practice factors of system-wide capacity development for climate-smart agriculture

Table C1.1 identifies good practice factors of effective capacity development interventions in the agriculture sector, and provides examples specific to agriculture in the context of climate change.

Good capacity development practice requires addressing all of these success factors to increase the likelihood of greater long-term sustainability, country ownership and scale of capacity development interventions.

Table C1.1. Good practice factors of effective capacity development for climate-smart agriculture

CSA cannot be limited just to production. The food systems themselves need to be climate-smart and resilient. It is crucial to consider all the stages of the supply chain subsequent to food production, since they form an integrated food system including reducing food losses. Gender considerations are particularly important to address exclusion and empowerment (FAO, 2012c).

Capacity Development Success Factor | Explanation | Climate-smart agriculture Examples |

|---|---|---|

Applying a system-wide approach across three capacity development dimensions interdependently | System-wide capacity development for more impactful and country-owned capacity development initiatives at scale involves three dimensions which are interlinked and need to be enhanced interdependently and through inclusive process:

| Based on a joint stakeholder assessment of capacity needs, capacities can be interdependently enhanced along three dimensions: Individual: strengthen the understanding, awareness and practical skills regarding climate change within relevant ministries such as the ministries of agriculture, environment, planning and finance. Organizational: enlarge mandates of relevant ministries to reflect climate change responsibilities, improve coordination within and between institutions, strengthen multi-stakeholder networks. Enabling environment: align environmental and agricultural policies with harmonized budget allocation to facilitate more effective adaptation and mitigation planning and implementation; Insert mitigation efforts into Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and in alignment with Sustainable Development Goals. |

Complementing technical with functional capacity development | Technical capacities refer to aspects such as increasing the competencies of people to intensify production sustainably or manage natural resources more effectively. Functional capacities are increasingly considered a necessary to complement technical capacity enhancement as they enable and empower actors to apply the new knowledge/skills effectively, and scale up the intervention’s results. Key functional skills to be enhanced include:

| Technical capacities (individual): increasing the competencies of people to intensify production sustainably or manage natural resources more effectively. Functional capacities (individual): planning and policy formulation to integrate technical skills for scaling up or negotiation skills complementing technical skills enhancement for trans-boundary, integrated water resources management. |

Promoting country ownership by aligning programmes with national priorities | National needs and priorities anchored in national ownership should guide capacity development interventions. For example, FAO follows country priorities as laid out in Country Programming Frameworks, which are the result of a joint collaboration effort and extensive dialogue and consultation with the country, National Agriculture Sector Plans, Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers, etc. and as per the Development and Aid Effectiveness Agenda. | Development of national reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (UN REDD) strategies closely aligned with country development strategies. See Case Study C.1.2. |

Jointly assessing capacities with stakeholders | Undertaking a careful assessment of needs through a participatory process to diagnose what and whose capacities need to be enhanced is a fundamental pre-condition for all successful and sustainable development projects at scale. Such participatory and inclusive assessments ensure that the context is understood and existing capacities and needs are identified, thus allowing the project or programme to be tailored to the local situation. It also provides spaces for dialogue, negotiation and consensus building (Scherr et al., 2012). See also module A3 on integrated landscape management. | See Case Study C1.10 for CSA capacity needs assessments in Kenya and Tanzania. |

Achieving sustainability by anchoring programmes to local or national institutions and systems | Successful and sustainable interventions anchor activities in local or national institutions, involving national actors early on when identifying needs and defining methodologies, approaches and desired outcomes. National systems, procedures, organizations, and/or budgets are developed to ensure long-term continuity even after external funding for development projects ends. | Most countries have established climate change organizational units to which CSA interventions should be linked and which foster climate change mainstreaming into development, e.g. National Climate Change Commissions or Offices. |

Promoting engagement with local and national actors | Encouraging national/local involvement in project/programme identification, formulation, implementation and monitoring, and the use of participatory communication approaches, ensure the endogenous support essential for sustaining projects in the long term. | The formulation of National Climate Action Programmes/Plans (NAPAs, NAPs, NAMAs) under the UNFCCC emphasizes this factor. |

Applying capacity development modalities beyond training | Alongside the delivery of training, other successful capacity development modalities include coaching, on-the-job mentoring, South-South cooperation, policy support, support to organizational development, farmer field schools, creating networks convening for national/ regional events, and strengthening institutional coordination. | See Figure C.2.2. with contextualized climate change learning examples in Case Study C1.4. |

Understanding national or regional contexts | Paying attention to national, regional and sub-regional contexts helps identify key drivers of change. | REDD + interventions need to be based on a sound understanding of the drivers of deforestation in a country. |

Using a long-term approach, given the capacity development process time | Capacity development takes considerable time, particularly at organizational and policy levels, and it happens gradually. Ensuring a medium- to long-term horizon, through different forms, scales or funding mechanisms, if necessary, can foster deep-level capacity development. | The shift in CSA interventions from a project to a programmatic approach supports this long-term approach. |

Monitoring capacity development | Monitoring of CD is particularly challenging due to the non-linear nature of change. This complexity requires participatory monitoring with stakeholders to track progress across the three dimensions. Such a participatory monitoring process enables spaces joint stakeholder learning, course adjustment if needed while continuously fostering country-ownership and commitment. | Transformation to CSA practice is knowledge-intensive and requires learning and changes in practice. This calls for innovative approaches to track this complex change process across the three dimensions (see section C1-4.3): Individual: Are farmers applying climate-smart practices as a result of a Farmer Field School approach? Organizational: Are relevant ministries and stakeholders better coordinating for planning and implementation of CSA approaches? Enabling Environment: Are relevant CSA policies aligned and being implemented in a participatory way? |