Sector Wide Approaches

Sector-wide Approaches (SWAps) aim to strengthen sector performance by increasing coherence and complementarity of interventions in support of a common policy framework. A SWAp is an approach to development assistance and not a set of clearly defined rules and procedures. A SWAp is not a lending instrument or a financing modality, rather it is a practical approach to planning and management, which identifies interrelated sector constraints and opportunities and addresses constraints and opportunities that require coordinated action across actors and subsectors. The adoption of SWAps has important implications for investment design and implementation. SWAps originally arose in the 1990s to enhance aid effectiveness, but it remains clear that national governments must be firmly in the lead to promote and implement SWAps. A SWAp should broaden national ownership over public sector policy and resource allocation decisions within the sector, bringing together government, non-state actors and development partners to implement a common agenda. SWAps have generally been built around a common sector programme, or, more recently, an investment plan. Recently full ownership and domination of public sector evolved to a wider stakeholders' partnership and prominent role of the private sectors (e.g. in the post CAADP NAIPs in Africa). However, to reduce fragmentation and transaction costs, procedures for implementation, including disbursement of funds, should be harmonized where possible, and should increasingly rely on government procedures for accessing public funds. All projects need to be aligned to the common results framework and should apply coherent monitoring procedures. Sector coordination occurs not only through greater dialogue, but through actual alignment of planning, implementation and monitoring. Including annual sector reviews as part of the budget cycle to review sector performance, impediments and implications for public spending during the next year can provide an important forum for debate and consensus development on improved implementation.

The origin and evolution of SWAps

SWAps were introduced in the 1990s, mostly at the initiative of development partners, to address perceived inefficiencies and ineffectiveness of aid. The main objectives were to reduce fragmentation and transaction costs and to increase the coherence of donor support. SWAps were also closely associated with a drive to promote budget support and oversight for individual donor projects, enhancing integration into the national financial management systems. At the same time, SWAps were designed to enhance policy coordination and implementation within a particular sector. The government was to be clearly in the lead, but SWAps were also intended to enhance dialogue and coordination with non-state actors, including producer organizations, civil society and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). As the international development agenda evolves from a focus on “aid effectiveness” to “development effectiveness”, this aspect of joint vision and coordinated action by all stakeholders, state and non-state, as well as development partners, under government leadership, has become the main focus of SWAps. The focus has shifted from aid delivery to sector development.

SWAps in agriculture

SWAps were first developed and implemented in sectors that have a significant public sector delivery role – in particular, health and education. SWAps in agriculture face a particular challenge, as most investment and expenditure in agriculture is made by the private sector – small and large, from primary production to final retail. The government’s role is primarily to create a conducive enabling environment that promotes greater and more sustainable investment to reach sector goals, and to ensure provision of public goods, such as research. Further, the public role in support of agriculture is often not limited to the realm of one particular ministry, but involves multiple line ministries and agencies at national and regional levels. SWAps in agriculture are an opportunity to enhance coherence in the public sector’s support to agriculture, in close dialogue with private sector stakeholders.

Evolution of SWAps in agriculture – the example of the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP)

In July 2003 the Maputo Declaration called for a pan-African flagship programme of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD). This led to the creation of CAADP. The Maputo Declaration stressed the need to allocate 10% of the national budget to agriculture and set an agriculture growth target of 6%. The implementation of the Maputo Declaration and CAADP process has provided clear evidence that private investment is the essential ingredient to stimulate and sustain agriculture growth. Moreover it became also clear that not all that is needed for agriculture growth to happen takes place in the agriculture sector or is within the mandate of the Ministry of Agriculture. In addition it is also necessary to create a favorable business environment for investments to happen. Therefore other ministries and actors need to be involved in the process.

The Malabo Declaration of June 2014 takes into account that growth can only be achieved if one looks at policies and actors beyond the agriculture sector. Subsequently the Malabo Declaration takes into account areas such as infrastructure, natural resources, land tenure, trade and nutrition. CAADP has evolved from a single-sector to a multi-sector approach, taking into account of related sectors that are required to stimulate agriculture growth. This requires inter-sectoral cooperation and coordination, an increased role of central government agencies in CAADP country implementation, National Agricultural Investment Plans as key vehicles but dependent on other implementation frameworks, and a focus on delivery and results (see Country CAADP Implementation Guidelines under the Malabo Declaration). Operationalization of the Malabo Declaration on accelerated African agricultural growth and transformation strengthened capacity will depend on two objectives, namely ‘Transformed agriculture and sustained inclusive growth’ and ‘Strengthened systemic capacity to implement and deliver results’ that cannot be achieved without a wider partnership between the public and private sectors, and the development partners (see Implementation Strategy and Roadmap to Achieve the 2025 vision of CAADP).

Elements of SWAp implementation

SWAps aim to address constraints and opportunities that require coordinated action across actors and subsectors. Process is important. A transparent and inclusive process for SWAp development is fundamental to achieve the necessary buy-in to permit greater coherence in implementation.

SWAps need to build on a thorough assessment of the sector and its major components2.

- Policies, plans and programmes – What is the “architecture” of policies and strategies, hierarchy and relationships? How are goals translated into implementation frameworks? Does the policy and legislative framework empower those responsible to move effectively towards the development objectives? Does the strategy advocate transparency, good governance, gender mainstreaming and environmental sustainability?

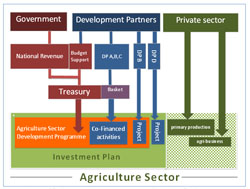

- Sector budget and fund flow – Which resources are available, and how are they allocated? Are public resources matched to plans and do resources flow to the appropriate levels for implementation, at the right time? Does public investment complement private investment?

- Actors, institutions and organizations – Who are the key actors in the sector, including government, private sector (farmers and agribusiness), civil society and development partners? What are their specific roles and how are they organized? How does information flow; what are the formal and informal channels of communication? What mechanisms exist for dialogue and coordination?

- Monitoring, learning and accountability – What are the mechanisms and instruments of monitoring and evaluation (M&E)? How are they used to ensure accountability (both internal domestic accountability and mutual accountability between partners)? To what extent are they used for learning purposes, such as informing new implementation cycles, or in processes of accountability?

- This assessment can form the basis for a jointly owned agenda for action to increase sector performance, building upon the strengths identified and addressing major weaknesses.

There can be no blueprint for SWAps in agriculture, as the policy frameworks and institutional contexts differ from country to country. Generally, these are the common elements that need to underpin a SWAp:

- A clear and nationally owned sector policy and strategy, and a results framework that guides action and sets expected results;

- A medium-term expenditure programme linked to the sector strategy that prioritizes action, while reflecting realistic estimates of available resources from domestic sources and development partners;

- Systematic arrangements for programming resources that reflect actual resource levels and implementation schedules;

- A performance monitoring system that measures progress, strengthens accountability and provides the evidence to underpin choices to improve prioritization and strategy;

- Clear and systematic consultation and coordination mechanisms that involve all significant stakeholders – state and non-state, domestic, and international development partners;

- Harmonized systems for budgeting, disbursement, accounting and procurement, or an agreed-upon process to more towards harmonization in these areas – especially where lack of harmonization is increasing transaction costs and reducing transparency.

Harmonization of systems can be a gradual process, whether for a simple system (e.g. harmonizing processes within one sector or for complex multi-sectoral, multi-country systems, and not everything has to be implemented through common systems. For example, support to strengthen performance of private sector or civil society organizations should not necessarily be delivered through the government funding mechanisms. However harmonization of complex systems is likely to being multi-layered that require coordination among and integration of several sectors and countries(e.g. task to be undertaken by the national Agricultural Sector Coordination Unit or Regional Coordinators for the RAIPs).

NB: This simplified graphic does not represent all possible funding sources, such as NGOs and foundations

A diversity of funding mechanisms may coexist. What is important is that regardless of the specific fund flow, interventions contribute to the common policy and results framework.

SWAps – the value added, and the challenges

SWAps are not ends in themselves but rather an approach to enhance results. Managed successfully, SWAps can:

- Create a common vision and purpose among diverse sector actors, on policy, strategy and spending;

- Enhance government leadership, while strengthening mutual accountability;

- Reduce transaction costs;

- Increase coherence of interventions in the sector;

- Strengthen overall results; and

- Make the agriculture sector more attractive for investment – i.e. more transparent and with a greater likelihood of positive results.

In practice, SWAps have generally increased government leadership, transparency and coordination. However, challenges also exist. Key challenges are:

- The split of institutional responsibilities for agriculture in the public sector, often leading to fragmentation of policy and implementation;

- Not all that is needed for stimulation agriculture growth takes place in the agriculture sector or is within the mandate of the Ministry of Agriculture. For example, Kenya established an Agricultural Sector Coordination Unit from 10 Ministries to act as the main coordinating body of the agriculture sector. Among its functions is the implementation of the Kenya Comprehensive African Agriculture Development (CAADP) Compact.

- The multiplicity of stakeholders, requiring that only those who really do have a stake are engaged in the process, to keep complexity down;

- Ensuring that the creation of coordination structures and mechanisms does not inadvertently increase rather than reduce transaction costs in the sector.

An incremental approach to SWAp development and implementation with regular, possibly annual, sector performance reviews, can ensure that the focus remains on achieving results in the sector and that the elements of SWAp approaches are clearly seen as means rather than ends, which may need to be adjusted in the course of implementation.

SWAps and National Agricultural Investment Plans (NAIPs)

SWAps have existed since the mid-1990s. NAIPs appeared in 2009. While both serve the same purpose, namely to increase food security and equitable agriculture growth, the main objective of SWAps is to strengthen national systems, a public domain. NAIPS by contrast focus on up-scaling of best agricultural practices, an objective, deeply rooted in the domain of the private sector. The NAIP is a sector-wide instrument and can be seen as a SWAp. In some countries it is replacing SWAps. There is a discussion around the question whether or not a NAIP is a SWAp, but it is important to not get lost in semantics. The NEPAD Country CAADP Implementation Guidelines under the Malabo Declaration provide a good overview of the characteristics of SWAps and NAIPs [1] (see table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of SWAps and NAIPs

| AG. SWAp | NAIP |

Purpose: | Increased food security and equitable agriculture growth | |

In existence: | Since 1990s | From 2009 onwards |

Original reason: | Ineffective aid and the collapse of country financial systems | Slow and uneven African agriculture growth |

Main objective: | Strengthened country systems | Up-scaling of best agriculture practices |

A new approach to: | Sector and aid management | Agricultural Investment planning |

Emphasis is on: | Government ownership and the policy dialogue | Country ownership, inclusiveness, evidence based planning |

Instrument for: | Public management of the sector and aid management | Planning of investment in the sector |

Focus is on: | Public expenditure by Government and DPs | Investment: by the public and private sector |

Scope: | Based on public mandate | Meant to be sector wide |

Role: | Addressing a public need | Exploiting private sector opportunities |

Leans towards: | Food security, rural employment | Agriculture growth |

[1]Note need to be taken that the CAADP process involves development of Regional Agricultural IPs, one for each Regional Economic Community. As such the SWAps take further layers of geo-political cooperation beyond the national sectors.

Footnotes

1Linkages between CAADP and Sector Approaches in Agriculture, presentation delivered at the CAADP Partnership Platform, March 2011

2Based upon Sector Approaches in Agriculture and Rural Development (EuropeAid, 2008).

3Adapted from FAO, 2007, Sector Wide Approaches

Key Resources

Investment and Resource Mobilisation Sector Wide Approaches (FAO, 2007) | Background material for a learning session on SWAps in agriculture, providing an overview of concepts and implementation experience. |

Sector Approaches in Agriculture and Rural Development (EuropeAid, 2008) | A reference document providing guidance on the use of sector approaches in agriculture to benefit sector development outcomes. |

SWAPs in motion. Sector wide approaches: From an aid delivery to a sector development perspective (EuropeAid, 2007) | A paper combining theoretical and practical perspectives on SWAp development and implementation. Developed in support of the EC’s Joint Learning Programme on Sector Wide Approaches (JLP) that offers sector-specific in-country learning events for development agency partners and domestic stakeholders |

Guidelines for using programmatic approaches in agriculture (ECOWAS/FAO, 2011) | A practical manual designed to strengthen the capacity of ECOWAS countries to implement sector wide approaches in agriculture |

Linkages between CAADP and Sector Approaches in Agriculture (Dietvorst, D, 2011) | Presentation delivered at the March 2011 CAADP Partnership Platform Meeting to delineate linkages between CAADP and sector approaches in agriculture, with a special focus on the role of national agricultural investment plans |

Supporting Agriculture Growth under CAADP using a Sector Wide Approach (FAO 2012) | Learning Materials from ECOWAS-FAO Learning Event on SWAps and CAADP. Guidance on key concepts linked to programmatic approaches and steps to move a programmatic approach forward. |

Formulating and Implementing Sector-wide Approaches (SWAps) in Agriculture and Rural Development (ARD) (Global Donor Platform on Rural Development, 2007) | Based on case studies this report assesses the extent to which SWAps in ARD are achieving their aims, their intended trajectories of change and provides key lessons for the future. |