Reducing pandemic risks by investing in better ecosystems and food systems

The huge economic and human cost of COVID-19 has focused minds on preventing the next pandemic, or drastically reducing the risk.

One vital solution is the adoption of the One Health approach – which recognizes that health of humans, ecosystems and animals – both wild and domesticated – are inextricably linked.

Two new reports from the World Bank and the FAO Investment Centre focus on reducing risks from wildlife and livestock, highlighting how governments in East Asia and the Pacific (EAP) can take practical actions to prevent pandemics.

“Investing in healthier ecosystems and food systems in East Asia and the Pacific can reduce global pandemic risks,” said Benoît Bosquet, Director, Environment and Natural Resources Global Practice, World Bank. “Enhancing coordination between the human health, animal health, and environmental health sectors is a key first step.”

Animal origin of emerging infectious disease

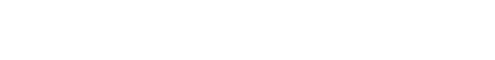

Most human infectious diseases have animal origins, with approximately 70 percent of emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) coming from wildlife.

Such diseases are increasing as a result of interactions with animals, as well as changes to the natural environment. Reducing close contact between wild and domesticated animals, and between animals and humans, play a key role in preventing the emergence, incursion and spread of infectious diseases with pandemic potential.

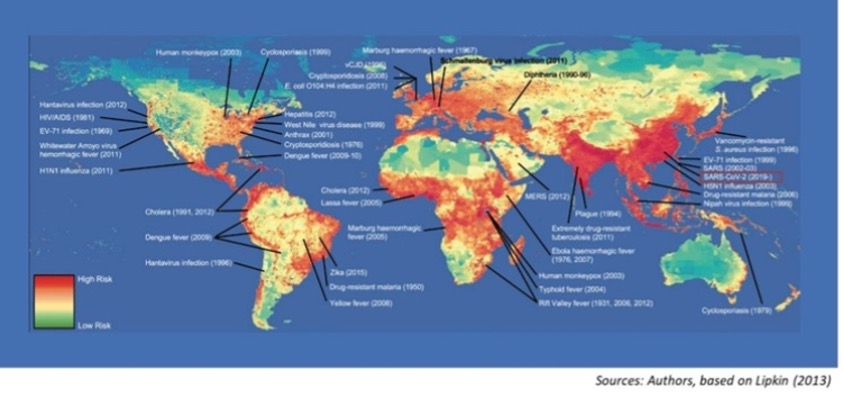

EAP countries are global hotspots for pandemic emergence. The region has also seen the highest economic losses from epidemics – which is estimated at USD 200 billion per year or 0.9 percent of the region’s GDP.

Previous EIDs – such as SARS, H5N1, H7N9, and Nipah – all came from EAP. Large and densely concentrated human settlements, high livestock populations, abundant wildlife, rapid urbanization and agricultural expansion increase the likelihood of pathogen spillover between humans and wild animals.

Climate change is increasing the transmission of both zoonotic and vector-borne diseases. Additional risk factors include escalating domestic and wildlife trade, deforestation and ecosystem degradation, inadequate livestock biosecurity and food hygiene practices.

Animal, human and environmental health sector integration

Critical data such as disease surveillance information, monitoring of wild and domestic animal movements and trade volume, or pathogen identification, are currently not routinely shared between animal, human and environment sectors.

Animal health and environmental health are neglected in terms of policy attention and investments – and remain the weakest links in One Health.

Institutional mandates for wildlife health surveillance and emerging disease prevention are lacking. While national and sub-national systems lack integration for disease prevention, detection, and response across all three sectors. Regional coordination for One Health is limited, as no single entity covers the whole region.

In many countries of EAP, insanitary conditions in animal production facilities and food markets raise the risk of disease transmission. Live animals and animal products are traded over long distances in complex value chains, making it difficult to trace the origin and spread of disease.

The sale of wildlife for food – such as rats, deer, foxes, bears, porcupines, civets, wild boar, waterfowl and bats – has developed into a significant industry with limited supervision by authorities.

Investment in prevention, detection and response

Economic analysis from the World Bank and FAO show that investments in One Health approaches make economic sense. However, aligning incentives is a challenge.

The benefits of preventing pandemics accrue at the national and global level, while the costs involved in reducing risk – through reducing deforestation, conserving biodiversity, monitoring wildlife trade, early detection and control, reducing spillovers, enhancing biosecurity of livestock farms, increasing surveillance of slaughterhouses and traditional markets – are mainly borne locally.

Investing in One Health should therefore be viewed as a global public good that also contributes to local health security priorities.

One Health funding gaps can be tackled at various levels. First, the international community should invest in regional disease surveillance and control programs for EIDs, programs on transboundary animal diseases and wildlife health, standards for safely and information sharing, trade protocols and inspection procedures.

Second, more local funds – both public and private – should be mobilized to manage interactions between humans, animals, and the environment, and to promote joint surveillance systems, better environments, and resilient agrifood systems.

Reducing pandemic risk and enhancing food safety

Improving animal production practices, ensuring the traceability of animal products, and enabling early detection of disease outbreaks, means that food safety is improved while pandemic risks are reduced.

"Working together on One Health will allow us to detect and control disease spread through stronger monitoring, surveillance and response systems, and reduce risk factors of pandemics by reinforcing capacities and infrastructure," said Mohamed Manssouri, Director, FAO Investment Centre. "Animal and human health, welfare and biodiversity must be addressed as a whole to ensure global health and protect our food systems from future crisis."

Reducing pandemic risk requires global attention, but practical steps are possible now at the regional and national levels, that will lead to better agrifood systems, a better environment, and a better planet.