Forest management planning in FMUs

The planning process in forest management units (FMUs) begins with an:

- assessment of the forest resource – including a forest inventory and often also environmental and social impact assessments;

- analysis of market and economic conditions – that is, an analysis of market opportunities for forest goods and services and other economic factors that may affect forest management; and

- assessment of the social, environmental, legal and other aspects – that is, clarifying the social, environmental, legal and other requirements for SFM, which set the framework conditions for the implementation of SFM in specific national and local conditions. This assessment may also include the clarification of tenure and government environmental licensing. The obligations of the forest manager or owner may include obtaining government approval for social responsibility agreements.

Continuous improvement through accumulating learning is an integral part of SFM, and forest management plans need to be reviewed regularly and revised accordingly as conditions change. Outcomes and impacts are evaluated and the learning from such evaluations fed into the revision of objectives, if needed, and the updating of the forest management plan.

The participation of forest stakeholders in the early and subsequent stages of forest management planning is crucial for the successful implementation of SFM. It will help in addressing conflicts that may arise over time and help ensure that local knowledge, interests and values are incorporated in the forest management plan (see Participatory approaches and tools in forestry).

Gender & forest management planning

Gender & forest management planning

It is essential that women are included at each stage of forest management planning. Indeed, excluding the voice of half of the population wastes considerable skills and knowledge. Yet too often, women are under-represented in relevant forest user groups and excluded from decision-making power with negative results.

Hearing from both women and men is particularly important, given that gender issues must be considered when designing forest management actions, since women and men may have different interactions with the forest and may be affected in differing ways by significant changes in the ecosystem, in resources and in policies.

Moreover, women’s participation in forest management institutions, such as forest user groups (FUG), raises incomes and promotes resources sustainability. Yet, they overwhelmingly tend to be under-represented in such groups and may have limited decision-making power.

Neglecting gender differences when planning can lead to severe consequences, both for women and for the environment of the forest. For instance, if only men are consulted, the choice of species and forest management techniques introduced may not be appropriate for all forest users, especially women (as men and women tend to rely on different resources).

Furthermore, if, as a result, women are forced to collect fuel wood or other essential products from greater distances, their workload increases and they can be put at risk of exposure to attack and might possibly be more exposed to sexual violence. This is also true for girls, who also are at risk of missing school or studies when they are forced to forage for forest products at a greater distance.

As a result, they may also be less likely to engage in education if their workload covers most of the day.

Assuring the participation of women and other marginalized groups is thus, crucial for sustainable and responsible forest management planning. Still, obstacles such as cultural barriers, discrimination in land tenure and ownership, and the lack of incentives for women remain.

Preliminary assessment:

It is particularly important to undertake a gender analysis while conducting the preliminary assessment. A gender sensitive assessment may include: tools for understanding when differences in land tenure and rights are dictated by rigid gender norms; collection of sex- disaggregated data related to the use of trees, planting and harvesting; analysis of gender barriers in accessing the markets; intersectional analysis that integrate gender with age, race, class.

Setting Management Objectives:

While setting those objectives, stakeholders should include a gender perspective, in order to respond to the needs of women and men equally.

Preliminary assessments

Preliminary assessments

Preliminary assessments should be carried out at the onset of the forest management planning process. Such assessments assist decision-making and help ensure the economic, social and environmental sustainability of the forest management plan. They may include:

- clarification of tenure;

- analysis of the legal status of the land;

- data collection on the biophysical (e.g. climate, topography and hydrology) and socioeconomic environments (e.g. demography, living conditions and local government);

- analysis of market opportunities for forest goods and services;

- analysis of other economic factors affecting forest management;

- social surveys (e.g. using rural appraisal methods);

- analysis of management scenarios based on inventory data in accordance with national and subnational laws, policies, strategies and plans; and

- cost–benefit analyses of options.

Forest inventory

Forest inventory

A forest inventory collects information on wood and non-wood forest resources, site classification, social aspects and biodiversity. Full inventories at the FMU level may be carried out periodically, and data should be integrated with geographic information systems to the greatest extent possible. Among other things, data from FMU inventories are typically used to estimate the annual allowable harvest of wood and non-wood products (see below, and also Forest inventory).

Setting management objectives

Setting management objectives

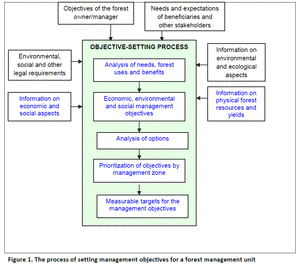

Well-defined management objectives are crucial for SFM. Adequate information and understanding of the social, cultural, environmental and economic conditions is necessary for setting these objectives (Figure 1).

A policy statement by the forest owner or manager expressing the philosophy, objectives and intended achievements of forest operations should be formulated. The management objectives should be formulated on the basis of this statement.

Forest management objectives are assigned with clear and measurable targets that state specific results to be achieved over the period spanned by the forest management plan. The task of the forest manager is to balance management objectives: forest management with a primary focus on a single product or purpose may affect the forest’s capacity to meet other objectives, and such tradeoffs should be recognized explicitly in the forest management planning process.

Managing forests for various products and services (i.e. “multipurpose management”) can potentially increase the monetary value that communities, managers and owners – who are sometimes the same people – obtain from the forest resource. For example, the production and harvesting of non-wood forest products (NWFPs) is increasingly being used to offset the costs of low-impact logging. (e.g. in timber concessions in Malaysia and Cameroun).

Zoning and stratification of an FMU

Zoning and stratification of an FMU

An FMU may have secondary management objectives that are not entirely compatible with the primary objective(s). To the extent that it is practicable, forest areas that are to be managed for different purposes, or have clearly different functions or values (e.g. conservation, production, community forestry, ecotourism and sacred groves), should be allocated to separately defined zones or compartments.

The zoning process includes the identification, mapping and management of wood-harvesting exclusion zones (or “set-asides”) of various types; these may include cultural areas, watercourses, water bodies and shorelines, landslip areas, conservation and protection zones, community forests, biological diversity conservation zones, wildlife conservation zones, scientific research zones and buffer zones. Geographic information systems and other techniques can be used to assist in forest mapping and zoning and for modelling alternative management options as aids in decision-making.

Forest management plans

Forest management plans

A forest management plan defines the planned forestry activities (e.g. inventory, yield calculation, harvesting, silviculture, protection and monitoring), specifying objectives, actions and control arrangements in a forest area. A forest management plan is also an important tool for ensuring the participation of, and communicating forest objectives and strategies to, people living in or near the forest and other stakeholders in the implementation of SFM.

A forest management plan usually applies to an FMU, which is an area of forest under a single or common system of management, as described in the management plan. An FMU may be a large, contiguous forest concession, a group of small forestry operations, possibly with more than one owner, or one of various other arrangements of forest land.

Detailed management planning for an FMU should involve three plans of differing duration and strategic importance:

- the strategic or long-term management plan, covering 20–40 (or more) years and reviewable every 5–10 years;

- the tactical management plan, a medium-term expression of the strategic management plan (e.g. covering successive 5–10 year periods), for example setting out the areas in which harvesting will take place during the period; and

- the operational plan through which the tactical management plan is programmed, implemented and monitored annually. The operational plan indicates the practical measures to be taken in the coming year, such as the types and scheduling of silvicultural measures and harvesting by compartment or stand, the opening up of skidding tracks, the construction of firebreaks, and other activities. The operational plan is also used for monitoring purposes.

Management planning at each of these three levels is essential.

Simple forest management plans. Several types of forest management plan can be distinguished depending on the overall forest management objectives and the type of forest manager (e.g. commercial forest enterprises or local or small-scale private forest users and owners). Although such plans are not mutually exclusive, they may vary in their complexity according to local circumstances and the nature of the forest management to be carried out.

Opportunities exist to significantly simplify all types of forest management plan, including those required by law. The broad guiding principles for preparing simpler forest management plans can be applied to a range of forest and socioeconomic situations.

Content of the plan. A forest management plan should include basic information that is directly relevant to forest management. It should state long-term management objectives and set out specific prescriptions and measures – in relation to protection, inventory, yield determination, harvesting, silviculture, monitoring and other forest operations – for achieving those objectives.

The forest management plan should specify:

- the maximum area from which forest produce may be harvested, or the maximum quantity of forest produce that may be harvested, or both, in a given period;

- the infrastructure needed according to the harvesting plan, local conditions and other relevant factors;

- the forest protection measures to be carried out;

- the forest development operations, including silviculture, to be carried out; and

- other matters that are necessary to achieve management objectives, such as forest inventory, mapping, technical and social surveys, monitoring, projections and public consultation.

Revision of the plan. The forest management plan should be reviewed and, where necessary, revised periodically in the light of accumulated experience, new information and changing circumstances. Each revision is an opportunity for forest managers to reconsider objectives and methods. In forest concessions, for example, a review should be conducted every 5–10 years over the course of the concession period.

Yield regulation and control

Yield regulation and control

Yield regulation is a central concept in SFM, particularly in natural tropical forests (which are usually managed under polycyclic harvesting systems). Yield regulation is the practice of calculating and controlling the quantities of forest products (e.g. standing volume of commercial timber and output/stock of NWFPs) removed from a forest each year to ensure that the rate of removal does not exceed the rate of replacement.

A sustainable yield implies that products removed from the forest are replaced by growth, with or without management interventions. In commercial forests where the major product is wood, calculating and implementing sustainable wood yields requires information on stocking levels and replacement rates (i.e. inventory and growth and yield data). Similar inventory data and calculations are needed for calculating the sustainable yields of NWFPs. Such information is used to construct yield tables and growth models, which can in turn be incorporated in the forest management plan.

Estimating sustainable levels of product harvesting. A commonly used measure is the volume of timber that may be cut in one year in a given area, known as the annual allowable cut (AAC). The AAC is calculated on the basis of the management objectives, the standing stock and growth rates of desirable (i.e. commercially valuable) tree species, and the area of forest under management. The AAC is a practical measure of the sustainable yield in a given period and can be used to monitor forest production and set limits for forest use. For some purposes the AAC is aggregated for all commercial species, but in forest management planning it is usually broken down by species or species group and by harvesting compartment or stand.

Where there is little or no information on the growth rates of desirable tree species (e.g. where forest management is being introduced for the first time), the AAC should be based on the classical empirical procedures most relevant to the FMU in question (see, for example, pages 158–159 in FAO, 1998) until adequate location-specific information is accumulated.

Yield prediction

Growth and yield predictions require high-quality data on tree growth, which are best obtained through the careful design and re-measurement, over time, of permanent sample plots. Growth and yield predictions and other ecological information should be compiled. Collaborative research can be a cost-effective means of obtaining data. FAO (1998) outlines the basic steps involved in the construction of yield prediction models.

Yield control

The division of the FMU into blocks or compartments and the defining of annual cutting areas and volumes are essential for the practical control of harvesting. Once the AAC has been reached, the block or compartment should be closed off and no more harvesting carried out until the next felling cycle (as specified in the forest management plan). Premature re-entry to harvested blocks should be avoided.

Records of production levels of wood and non-wood products must be maintained for each harvested compartment or block and reconciled against predicted yields to ensure that the AAC is not being exceeded. This information is also essential for predicting future growth and yield and for the accurate revision of yield levels, and it helps provide management continuity over time.