Melbourne, Australia

Background

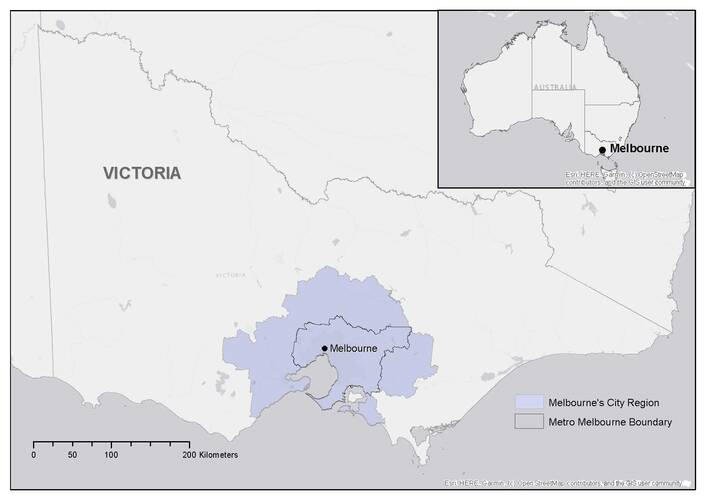

Melbourne is the capital city of the state of Victoria in south-eastern Australia. The Greater Melbourne metropolitan area has a population of around 5 million people (2021). The city’s population has grown rapidly over recent decades, and it is predicted to outgrow Sydney by 2030 to become the largest city in Australia.

Melbourne has a temperate climate. It is in a warming and drying region of the world that is experiencing the impacts of climate change. Rainfall is decreasing, and the region has experienced severe droughts, including the Millennium Drought between 1997 and 2009.

The city region food system of Melbourne

Melbourne’s city region food system has been defined as the 31 local government areas that make up metropolitan Melbourne and another 9 local government areas that form a second peri-urban ring around Greater Melbourne.

Melbourne’s city region produces a variety of foods and is particularly important for production of perishable foods, such as fruit, vegetables, eggs and chicken meat.

Around half of the vegetables produced in the state of Victoria grow in Melbourne’s city region. In 2015, this region produced enough food to meet around 41% of the population’s demand for food in Greater Melbourne (metro Melbourne), including around 82% of the city’s demand for vegetables.

Main challenges for the Melbourne city region food system

The main climate shocks and stresses facing Melbourne’s city region food system include sudden shocks, such as fire and flood, and chronic stresses, such as drought.

The mean temperature in Australia has risen by over 1°C since 1910. As temperatures continue to rise, Melbourne is likely to experience more extreme weather events associated with climate change, including more extreme temperature days and more frequent and severe heatwaves and droughts.

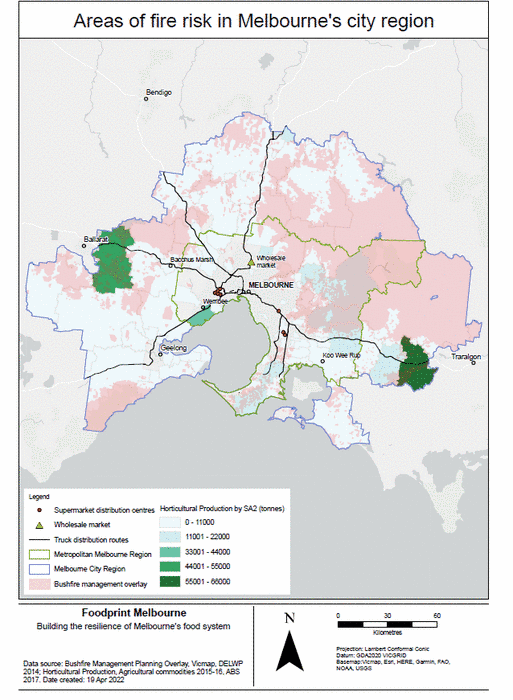

- Fire. Melbourne is in one of the most fire-prone regions of the world, and climate change is leading to harsher fire weather, with more high and extreme fire danger days and more frequent fires. Greater Melbourne and the interface areas on the fringes of the city have many areas of high fire risk, and a major bushfire event in the region has the potential to cause significant disruption to the city’s food system.

The following map shows areas of fire risk in Melbourne’s city region.

(Data sources: Bushfire management Planning Overlay, Vicmap, DELWP 2014; Horticultural Production, Agricultural commodities 2015-16, ABS 2017)

- Drought. Between 1980 and 2020, most of Victoria experienced a decline in annual rainfall. The Millennium Drought from 1997 to 2009 saw the lowest total inflows to Melbourne’s water supply on record. Rainfall is likely to continue to decline in the Melbourne region, and droughts are likely to increase in duration and frequency.

- Flood. The Melbourne region is at risk of riverine and storm water flooding. Although overall rainfall is decreasing in Victoria, the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events is increasing due to climate change.

- Sea level rise. The risk of coastal inundation and salt water intrusion in low lying areas of Melbourne is increasing due to sea level rise and more frequent extreme wave and storm tide events. The mean sea level at Williamstown in Melbourne’s west has risen by approximately 2 mm per year since 1966 (DELWP, 2019). Sea levels will continue to rise as the oceans warm.

- Compound shocks and stresses. Multiple extreme weather events related to climate change may occur together, compounding the overall risks and impacts. For example, drought conditions and heatwaves lead to increased bushfire risk. Extreme rainfall, storm surges and sea level rise can combine to increase the magnitude of coastal inundation. Climate shocks and stresses are also increasingly likely to co-occur with other non-climatic shocks. The COVID-19 pandemic followed closely on the 2019-2020 bushfires in south-east Australia, leaving little time for recovery in between.

Main impacts on the CRFS

Food production

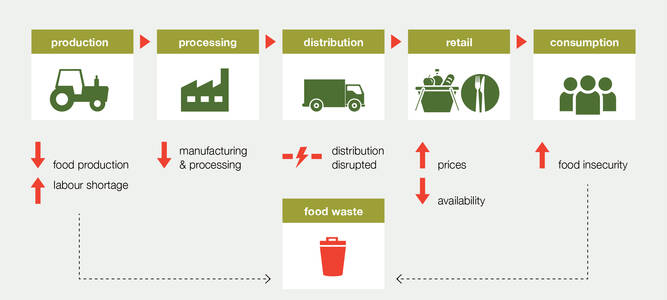

The 2019-2020 bushfire crisis in Victoria had significant impacts on the food system in the state. Roads were closed, and transport and telecommunications infrastructure was impacted. Many of the fire affected areas were already experiencing or recovering from drought.

Food production systems are vulnerable to bushfires. Agriculture is affected during bushfires by the destruction of farm infrastructure, loss of crops and livestock, and smoke taint in crops. Soils can be damaged by the intense heat of bushfires and are more susceptible to erosion after loss of vegetation. It is estimated that 22% of agricultural land was burned in fire affected areas during the 2019-2020 bushfires (Bushfire Recovery Victoria, 2020).

Food processing

Food processing and manufacturing enterprises were impacted by the 2019-2020 bushfires in fire-affected areas. However, the most significant disruptions occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Disruptions to global trade during the pandemic highlighted the reliance of food manufacturers on imported materials. Supplies of some additives, packaging and frozen produce were delayed, leading to temporary shortages and price increases.

Meat processing was affected by significant COVID-19 outbreaks in Victoria. Abattoirs and other processing plants, where large numbers of people work in close proximity, were particularly vulnerable.

Food distribution

Road and rail closures during fire and flood emergencies can disrupt the transportation of food and affect the quality and availability of fresh produce.

During the 2019-2020 bushfires, road closures in fire-affected areas impacted food freight to other parts of Victoria and interstate freight between Victoria and the neighbouring state of New South Wales. Some food freight had to be rerouted, adding time and cost to delivery, which particularly affected transportation of perishable foods like fresh vegetables.

Food distribution was also disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The grounding of passenger planes reduced air freight capacity by over 90% (Australian Food and Grocery Council, 2020), which affected food imports and exports. Food imports were also affected by reduced shipping and container capacity, disruptions to port operations and delays in customs clearance.

Food retail

The 2019-2020 bushfires had a significant impact on supermarkets and other food retail stores in fire affected areas. Some stores had to close and some lost stock due to power outages. There were localised food shortages in bushfire affected communities.

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on food retail were more extensive. Food sales in supermarkets and grocery stores rose 23% in March 2020 due to a sudden increase in consumer demand at the start of the pandemic. There were huge increases in sales of some foods. Sales of some types of frozen vegetables were up 1000% compared to the same time the previous year (Australian Food and Grocery Council, 2020).

During the Omicron wave of the pandemic in early 2022, supermarkets again faced food supply shortages. The number of workers isolating throughout the food supply chain significantly reduced supplies, particularly of fresh foods, such as chicken meat and fruit and vegetables.

Consumption

The COVID-19 pandemic had widespread impacts on food consumption across Victoria. People in Melbourne were particularly affected due to the number of lockdowns in the city and their duration. Melbourne spent more days in lockdown than almost any other city in the world during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021).

People in Melbourne faced temporary shortages of food in supermarkets at times, and rising unemployment and loss of income during lockdowns led to an increase in food insecurity. The people who are most impacted by changes in food availability and food prices due to shocks are those who are already at risk of food insecurity, particularly people on low incomes.

Food waste

During the 2019-2020 bushfires, there was food loss on farms directly impacted by the bushfires, and increased food waste elsewhere in the food supply chain due to power outages and delays in transportation.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, there was increased food loss and waste on Victorian farms when the hospitality industry shut down. Some farmers who sold directly into the sector were unable to sell produce and had to plough crops back into the soil. There was also significant food waste in the food service distribution sector that supplies produce into hospitality.

The following figure summarises the impacts of the 2019-2020 bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic across the food system.

__________________________________________________________________

*This research on the resilience of Melbourne’s city region food system to shocks and stresses is an independent parallel project to the City Region Food System Programme. It is led by the Foodprint Melbourne research team at the University of Melbourne.

Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation has proudly funded The University of Melbourne’s Foodprint project since 2015 and continues to be the only external philanthropic partner.

The Foundation is working to create a more climate resilient and inclusive Melbourne. lmcf.org.au