Toronto and the Greater Golden Horseshoe, Canada

Background

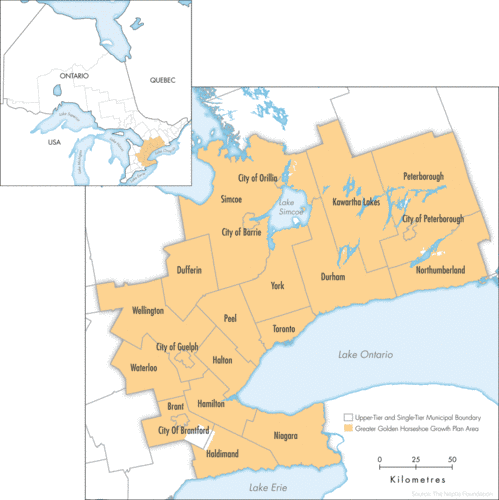

In Canada over 80% of the population lives in cities, with almost ¼ of Canada’s total population living in the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) area. Toronto’s City Region –defined as the GGH area- stretches in a curve around the western side of Lake Ontario, with the city of Toronto occupying the northern side of the horseshoe.

The Toronto - Greater Golden Horseshoe city region

The Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) City Region includes the City of Toronto and 15 surrounding counties. The GGH is an area with high potential food production as well as rapid population growth, creating a mix of legitimate demands that are difficult to reconcile including, for example, the demand for housing and residential infrastructure that conflicts directly with preserving prime agricultural lands. Food insecurity is a significant challenge in Toronto and in surrounding areas. In the City of Toronto, 31 of 140 neighbourhoods fall below the Neighbourhood Equity Benchmark signalling food access challenges, low income and other equity issues requiring immediate attention. The ‘Cultivating Food Connections’ study for Toronto shows that expenditures are not going to local farmers or local economies. The average food journey from farm to table was estimated at 4497 kilometres in 2015.

Main challenges for the Toronto –GGH City Region Food System

An assessment of the status and performance of food systems in the GGH was conducted under the guidance of RUAF and the Laurier Centre for Sustainable Food Systems in cooperation with Toronto Public Health. Four key challenges were identified through the two-year process including: lack of mid-scale infrastructure, food access and related food insecurity, the need for food policy supports beyond the GGH and improved labour practices.

Food infrastructure: In 2015, the GGH included 19,266 farms providing more than 35,500 farm-related jobs and adding more than 12 billion CAD annually to the economy. Provincial food processing is concentrated in the GGH and provides more than 200,000 jobs with more than 520,000 jobs in food distribution, retail and food service. Despite this robust economic performance, the area under cultivation declined by 4.4% between 2006 and 2011. A further challenge is the strong export focus of the food system. Food flow analysis and case study research for the GGH confirmed that either: 1) production does not meet local demand. The deficit for carrots is about 2.9 million pounds, for apples 283 million pounds, for eggs 535 million dozen and for chicken meat 109 million kilograms. 2) Despite these gaps, food leaves the region while comparable foods are imported; for example, it is estimated that 25 percent of carrots produced are exported and 20 percent of carrots consumed are imported. This mismatch was confirmed as the major logistical challenge for the GGH food system. The lack of mid-scale appropriate infrastructure undermines the ability of local producers to sell into markets in the GGH and compromises consumer’s ability to access healthy local food.

Food access and food insecurity: On the consumer side, food insecurity ranges between 10 and 17.6% even though food typically represents less than 10% of household budgets. The Greater Golden Horseshoe has numerous examples of innovation and commitment to reduce food insecurity through community food organisations and food banks. The solutions tend to be regionally focused, both for supply and for distribution. Among those interviewed for the CRFS research, food bank organisations indicated they are rethinking their model in many cases to focus more on logistics streamlining, fresh food and regional production. As the farmgate prices have been squeezed by powerful grocery corporations, food banks have recognised the value in redirecting their funds to healthier food that benefits the local economy. For marginalised groups, the struggle between the various models is resolved in yet another way through organisations such as the Afri-Can Food Basket, Black Creek Community Farm and efforts of the Black Farmers Collective. These organisations insist that growing and distributing to marginalised groups must be owned and operated by members of the community.

Labour practices: Labour was frequently raised by stakeholders with a focus on opportunities and trends towards decent work in all food system areas. Most jobs in the agri-food sector are in food service, which tend to be precarious jobs with low pay (GHFFA, 2016: 14). Food service (for instance, fast-food chains) do not realise the full potential of food or agriculture multipliers. Revenues for large transnational corporations tend to leave the local economy; expenditures (supplies, management, planning) are made elsewhere.

Food Policy supports beyond the GGH: While Toronto has one of the oldest Food Policy Councils in the world, there is a need for policy supports beyond city boundaries. Provincially, Ontario instituted a Local Food Act in 2013. Its three goals are to: increase consumer awareness and education; improve access to local food; and, ensure that there is sufficient supply to meet demand. While the commitment is laudable, there has been less change than expected as demonstrated through the CRFS findings.

The Way Forward

Eight key policy recommendations emerged through the CRFS project and were assessed and grouped to identify priorities. The top policy recommendation is to create mid-scale infrastructure and provide financial, regulatory, public food procurement and educational supports, such as food hubs, to further develop regional food flows. Associated recommendations include providing financial resources, developing appropriate regulations, and increasing related educational and research support to foster mid-scale infrastructure.

Since the end of the GGH CRFS process in June of 2016, there has been significant food policy activity at multiple scales. For example, as outlined in the 2017 Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe: “Municipalities are encouraged to implement regional agri-food strategies and other approaches to sustain and enhance the Agricultural System and the long-term economic prosperity and viability of the agri-food sector, including the maintenance and improvement of the agri-food network.”

More recently and in 2018, the federal government has undertaken a national consultation with the goal to launch a National Food Policy in 2018. It is hoped this will provide increase attention to local food flows and capture the benefits of City Region Food Systems. In addition, the Canadian Federal Government is moving towards a National Food Policy and released a Standing Committee report in December 2017 that includes consensus on the importance of mid-level infrastructure for the future Canadian food system.

While no straight lines can be drawn from the CRFS work in Toronto to these policy initiatives, we can conclude that the strong and long-term food policy leadership in Toronto that is captured in and continued through the CRFS work helped to shape these other food policy initiatives directly or indirectly. There are also food policy initiatives with the city, including a reinvigoration of the Toronto Food Strategy that are informed directly by the CRFS work.