Forests, food security and nutrition

Welcome to the module on Forests, food security and nutrition. This module is intended for public and private forest and land managers who wish to increase the contributions of forests and trees outside forests to food security and nutrition. The module provides practical knowledge, strategies and tools for using sustainable forest management (SFM) to do so.

Basic knowledge

It is estimated that 795 million people are chronically undernourished. Forests make up one-third of the Earth’s land area, and another half of the total land area has sparsely scattered trees. An estimated 2.4 billion people worldwide depend in various ways on forests and trees outside forests for their food security and nutrition. For example, more than 50 million people in India depend directly on forests for food consumption and good nutrition. In 2011 it was estimated that 80 percent of people in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic consumed wild forest foods daily.

Food security can be defined as the state in which “all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”. Food security is fully achieved when food is physically available (availability); economically, physically and socially accessible (access); and usable (utilization); and when these three conditions are stable over time (stability). Each of these dimensions of food security is affected by the health and vigour of forests and trees outside forests; therefore, the role of SFM is vital for sustainable food security and nutrition.

Related modules

- Agroforestry

- Forest tenure

- Health benefits from forests

- Management of non-wood forest products

- Mangrove ecosystem restoration and management

- Market analysis and development of forest-based enterprises

- Watershed management

- Wildlife management

Forests, food security and nutrition contributes to SDGs:

In more depth

The global population is projected to increase from 7.3 billion in 2015 to 9.5 billion in 2050, with most of this growth taking place in the developing world. Ensuring the food security of a population of 9.5 billion people will require an increase in food production of 60 percent globally and nearly 100 percent in developing countries, even without taking into account the ongoing “nutrition transition” in many emerging and developing countries, in which the intake of foods such as meat and dairy products is increasing. The daunting challenge of achieving food security for a growing global population is made even more complex by the looming threat of climate change and an associated increase in the frequency and severity of weather events, as well as by growing water and land scarcity, soil and land degradation, a deteriorating natural resource base, and food price volatility.

Although sustainably managed forests, and trees outside forests, contribute to food security and nutrition in many ways, those contributions are largely misunderstood, underestimated and inadequately considered in policies. The following sections discuss the main contributions of SFM to food security and nutrition.

Resources

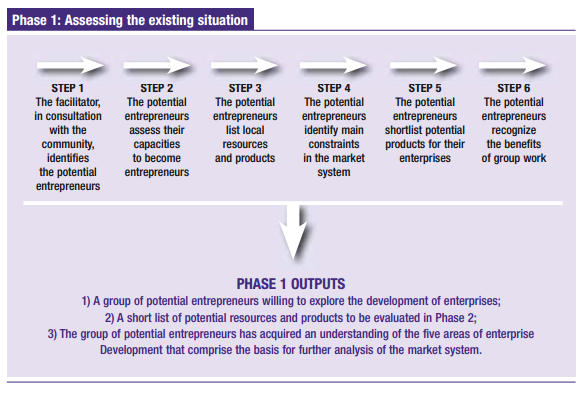

Phase 1 is exploratory; its purpose is to investigate the existing situation. During this phase, potential entrepreneurs:

- obtain an overview of tree and forest resources and potential products;

- identify the constraints and opportunities of those resources and products;

- shortlist a range of products; and

- understand that working in a group can create a stronger market position.

Phase 1 should provide a realistic indication of enterprise prospects, taking into consideration the available resources, social conditions, financing, market demand and potential investors. The objective is to help potential entrepreneurs discover the products that are best suited to their economic situations while ensuring that the resource is used sustainably. To create viable enterprises and reduced risks, potential entrepreneurs learn to select enterprise ideas that take into account social, environmental, institutional and technological factors.

In Phase 2, the potential entrepreneurs gather the information they need to assess the viability of the products and services shortlisted in Phase 1 and decide on the most sustainable and appropriate type of enterprise. In-depth feasibility studies are conducted on shortlisted products and services to evaluate the scale of potential markets, analyse trends and identify constraints to market access. The most promising products and services are selected on the basis of these feasibility studies.

The aim of Phase 3 is to formulate an enterprise development plan that integrates all the strategies and services needed for the success of the new enterprise. The plan is then analysed to assess the assistance the entrepreneurs will need to start their enterprises.

In Phase 4, entrepreneurs are guided through the process of obtaining funds to set up their enterprises and the training they need, as identified in their enterprise development plans. Entrepreneurs are assisted in starting up their enterprises, and they learn to monitor the activities of their enterprises. In this pilot phase, entrepreneurs can test their capacity to link with business service providers and refine their operational and organizational mechanisms. Finally, entrepreneurs are trained to strengthen their abilities in marketing and natural resource management.

Business services. How to obtain financial services to provide investment, working capital, insurance and savings facilities is a crucial consideration in the enterprise development process. Businesses linked in the value chain can provide financial services to one another; financial institutions (e.g. banks) are another potential provider.

Non-financial business development services might be needed for a range of non-financial inputs, such as:

- operational or generic services, to provide, for example, training and skills development and information and advice on technology information; and

- strategic or specific services, such as networking and brokering, market information and research, packaging and advertising.

Supporting forest enterprise development. Support programmes for small and medium-sized forest enterprises should pay careful attention to the context in which they hope to operate. An assessment of potential areas of growth is critical to any preliminary analysis of enterprise support. Different approaches may be needed, depending on whether the target region is forest-rich or forest-poor and politically stable or in a post-conflict situation.

It is important to distinguish between support to help the very poor survive and avoid descending into greater poverty, and support that will build assets sufficient to climb out of poverty. Equity concerns should also be central to considerations throughout the support process.

Supporting institutions can help improve the business environment for small and medium-sized forest enterprises. The main components of the business environment are:

- general macroeconomic policies;

- the legal and regulatory framework, which translates policies into practical laws and regulations – with their associated costs of compliance; and

- the institutional (or organizational) framework, which coordinates the regulation, promotion, monitoring and representation of both the macroeconomic environment and small and medium-sized enterprises.

The market analysis and development approach focuses on flexible, demand-led interventions. For it to succeed, it is critical that facilitators do not provide actual services but, rather, that they build capacity to provide the services and link service providers with those who most need them.

Further detailed guidance and support can be found in the tools and cases of this module.

Women and men can have different roles in establishing forest-based enterprises in developing countries. The entrepreneurship of women in forestry may be constrained by cultural, economic and social obstacles. Among them: centralized ownership and difficultly gaining access to natural resources, cultural barriers to access markets, and poor access to extension, technologies, training and credit.

Although many women have a high-level knowledge of sustainable management of forestry, species diversity and conservation methods, they often have few opportunities to apply this in their own enterprises. In fact, despite the lack of sex-disaggregated data, available research shows the trend is that women are mostly confined to small-scale retail trade, while men run larger businesses. Women work predominantly in the informal sectors, as primary collectors and sellers of Non-Wood Forest Products (NWFPs), while men dominate more formal sectors and the timber trade. Moreover, the presence of women at a managerial, technical and professional level is still low. This is mainly due to traditionally defined gender roles.

Important improvements would include collection of

sex-disaggregated data, and the creation of networks and associations of

women to increase their political and economic weight. It would be

valuable to conduct gender-disaggregated value-chain analysis of

mainstream forest timber and non-timber forest products to be considered

in the policy-making process and technical research.

Agbeibor, W. Jr. 2006. Pro-poor economic growth: role of small and medium sized enterprises. Journal of Asian Economics 17, pp.35-40.

Beaver, G. 2002. Small business, entrepreneurship and enterprise development. Pearson Education Limited.

Butler, D. 20006. Enterprise planning and development small business and enterprise start-up survival and growth. University of Kent.

Donovan J., Stoian, D. & Poole, N. 2008. Global review of rural community enterprises. The long and winding road to creating viable businesses, and potential shortcuts.

FAO. 2013. Smallhoder integration in changing food markets.

Gibb, A. & Li, J. 2003. Organizing for enterprise in China: what can we learn from the Chinese micro, small, and medium enterprise development experience. Futures 35, pp.403-421.

Hallberg, K. 2000. A market-oriented strategy for small and medium enterprise. World Bank.

Hoffmann, W.H. & Schlosser, R. 2001. Success factors of strategic alliances in small and medium-sized enterprises - An empirical survey. Long Range Planning 34, pp. 357-381.

Manu, Y., Iddrisu, A. & Yoshino, Y. 2012. How can micro and small enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa become more productive? The impacts of experimental basic managerial training. World Development, vol. 40, no3, pp.458-468.

McPherson, M. 1996. Growth of micro and small enterprises in Southern Africa. Journal of Development economics, vol. 48, pp.253-277.

Mead, D.C & Liedholm, C. 1998. The dynamics of micro and small enterprises in developing countries. World Development, vol. 26, no 1, pp.61-74.

Moore, S.B. & Manring, S. L. 2009. Strategy development in small and medium sized enterprises for sustainability and increased value creation. Journal of Cleaner Production 17, pp.276-282.

Nair, CTS. 2007. Scale markets and economics: small scale enterprises in a globalizing environment. Unasylva 228, vol. 58, pp.3-10,

Nichter, S. & Goldmark, L. 2009. Small firm growth in developing countries. World Development, vol. 37, no 9, pp.1453-1464.

Piatkowski, M. 2012. Factors strengthening the competitive position of SME sector enterprises. An example for Poland. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences. 8th International Strategic Management Conference.

Peres, W. & Stumpo, G. 2000. Small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises in Latin America and the Caribbean under the new economic model. World Development, vol. 28, no 9, pp.1643-1655.

Rocha. E.A.G. 2012. The impact of the business environment on the size of the micro, small and medium enterprise sector; preliminary findings from cross-country comparison. Procedia Economics and Finance, International Conference on small and medium enterprise development with a theme: innovation and sustainability in SME development.

Rogerson, C.M. 2001. In search of the African miracle: debates on susccessful small enterprise development in Africa. Habitat International 25, pp.115-142.

Molnar, A., Liddle, M., Bracer, C., Khare, A., White, A. & Bull, J. 2007. Community-based forest enterprises. Their status and potential in tropical countries. ITTO Technical Series no.28.

This module was developed with the kind collaboration of the following people and/or institutions:

Initiator(s): Sophie Grouwels - FAO, Forestry Department

Contributor(s): Kata Wagner, Jeremie Mbairamadji - FAO, Forestry Department

Reviewer(s): Tropenbos International

This module was revised in 2017 to strengthen gender considerations.

Initiator(s): Gender Team in Forestry

Reviewer(s): Sophie Grouwels - FAO, Forestry Department