People for trees, trees for people

FAO and local communities host “mapathons” to monitor tree restoration using geospatial tools

Tasked with using geospatial technology to count trees in a remote region of northeast Nicaragua, Rene Zamora, a Forest Economist from the World Resources Institute (WRI), had three priorities.

First, he found some unused space in a local school building in the town of Bonanza; second, he contracted with a satellite provider of Internet services; and third, he spread the word so that local people could help. Most of his recruits worked in cattle ranching and agriculture and had never used a computer before – but they were keen to give it a try.

The end result was an FAO-WRI “mapathon”, where local people first learned the necessary computer skills and data-collection techniques before applying this knowledge over the rest of the week, all with the goal of creating a high-resolution map of where the region’s trees are.

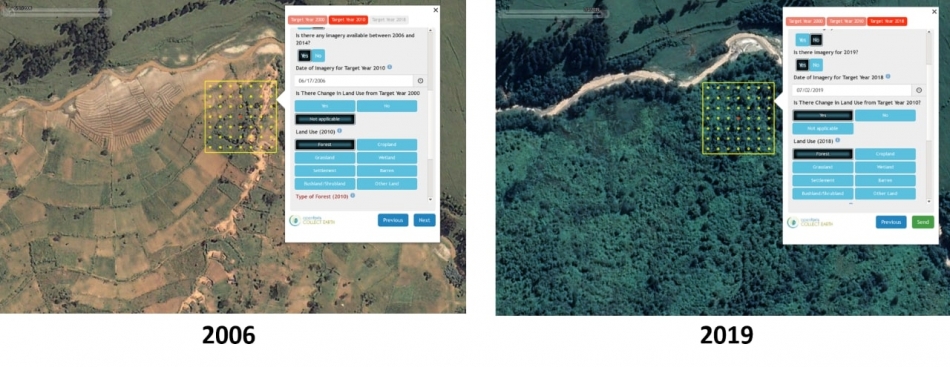

Mapathon participants are trained to scour geographic micro-ranges in their home territories and identify individual trees. This is done through FAO’s Open Foris tool, Collect Earth, which uses freely available images from NASA, the European Space Agency, Google Earth and Planet Data from Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative. This detailed imagery allows people to see objects as small as half a meter and go back in time to assess any changes in the land.

Using this Collect Earth tool, experts and locals were able to update previous surveys and monitor the restoration progress of tree cover.

This mapathon in Nicaragua, co-organised by FAO and WRI, is just one example of how Open Foris, a free and open-source software tool designed for efficient data collection, analysis and reporting, can help communities and governments assess and restore their ecosystems.

The community’s involvement in the mapathon in Nicaragua was crucial to regenerating their forests, simultaneously building trust in and local ownership over restoration activities. ©WRI

Around the world

In fact, FAO and WRI are helping dozens of governments, research institutions, civil society organizations and local communities around the world to produce their own actionable data, just like in Nicaragua. Recently, the European Union (EU) has also started a series of initiatives using FAO-powered mapathons to generate new insights into its own urban, natural and farm geography.

Validated data compiled in Collect Earth is then plugged into another Open Foris platform, the System for Earth Observation Data Access, Processing and Analysis for Land Monitoring (SEPAL), which is FAO’s cloud computing geospatial data processing platform. It creates custom maps that provide information about the entire landscape.

After training, a person can analyse up to 80 plots per day. It’s impressive, but working at that scale not only takes time, it also needs to be done by local people who are familiar with the land and know how it is used.

“Local people really know where the trees are,” said Zamora, who led that project. “They make fewer mistakes.”

That’s critical because counting trees in agricultural and degraded areas has traditionally been harder to tally than those in forests, so local knowledge is vital. This helps governments and communities around the world establish virtual inventories of their trees, which we know to be key carbon sequestration actors. Concentrating on locally relevant information also builds ownership and trust in restoration actions, while community participation in monitoring bolsters that and provides more granular high-quality data.

Why do we need to track tree coverage?

“Good local monitoring is needed both to track successes and failures,” said Julian Fox, FAO’s Team Leader of National Forest Monitoring. “It can catalyse and scale investments in the successes and enable adaptive management when things are not going well.”

For example, a mapathon in Ethiopia found one district had barely increased its forest cover from 2010 to 2015, putting it far behind its goal. Cue accelerated efforts from the public sector to redress the balance. In one part of India, local participants identified points where tree cover existed and where growing more could be successful. After this, private efforts took off. In Rwanda, the Gatsibo District had an ambitious target of raising forest cover to 30 percent of its territory. The mapathon exercise actually revealed more trees than expected around homes and grasslands, which showed great potential to meet that goal and even further increase the number of trees.

Mapathons are a way to integrate different stakeholders, including government forestry officials with their priorities and smallholder farmers with theirs.

Thanks to the use of historical satellite data sets, mapathon exercises also allow governments and communities to see changing patterns over time, such as this example of successful restoration from Rwanda. ©FAO

Building momentum for the decade ahead

2021 kickstarts the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, and these mapathons will play a vital role in helping communities and governments understand which ecosystems are under threat and what needs to be done to tackle the problem.

“FAO is leading efforts to deliver open and accessible geospatial solutions to member countries and communities through initiatives such as SEPAL,” said Fox. “Engaging and empowering communities to collect and create their own information on forest restoration is critical and allows for local adaptive management in a changing climate.”

FAO is further advancing this work with the development of a new Framework for Ecosystem Restoration Monitoring (FERM) platform built on FAO’s Hand-In-Hand Geospatial Platform architecture. FERM deploys geospatial data to help monitor and report restoration progress for all ecosystems: terrestrial and aquatic, biophysical and socio-economic. We have to know where we are to know where we are going, and monitoring is a foundational step as we move into the Decade of Restoration.

Learn more

Website: National Forest Monitoring

Website: Open Foris

Flyer: SEPAL

Website: FAO & Forests

Video: Mapping Together

Website: UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration

This post was originally featured on the FAO website: http://www.fao.org/fao-stories/article/en/c/1414034/